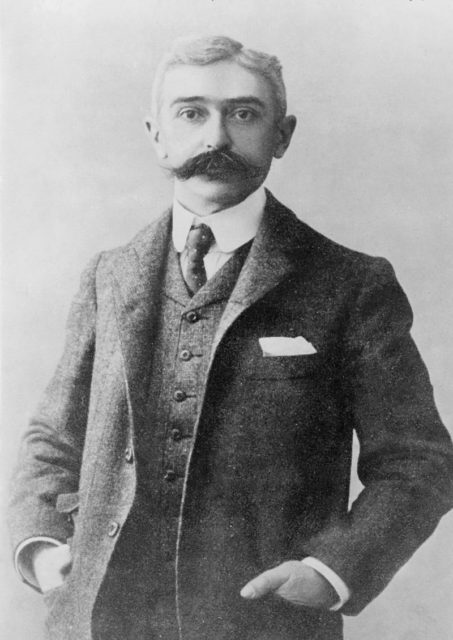

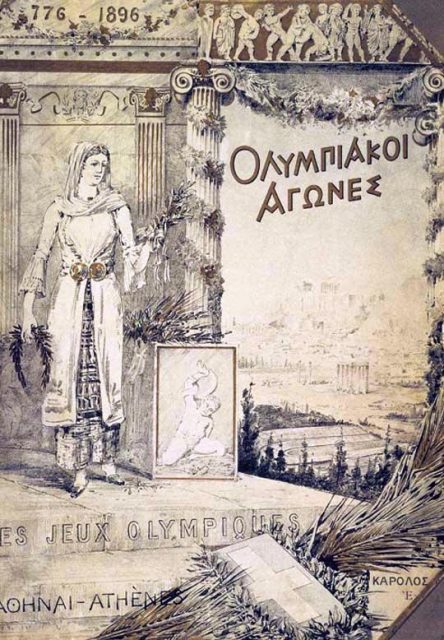

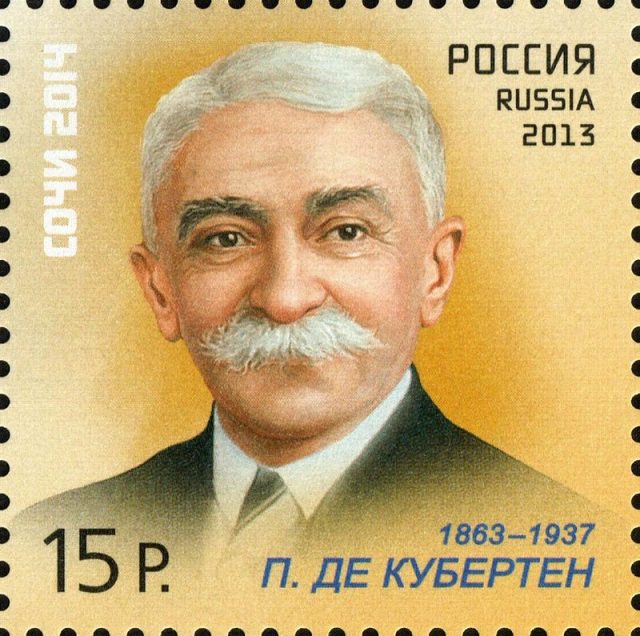

When Baron Pierre de Coubertin restarted the Olympics in 1896, he was adamant that it should emulate not just the physical sportsmanship of the original competition (albeit with less nudity) but should reflect what it truly meant to be an Olympian.

For the baron, who was classically trained, a true Olympian was someone who was able to show prowess on the sports field and was able to hold their own when it came to artistic pursuits.

It took the Baron almost ten years to convince the Olympic Committee to get on board with his vision for a well-rounded Olympic Games.

The Baron was very much a man of conviction and declared at the time: “There is only one difference between our Olympiads and plain sporting championships, and it is precisely the contests of art as they existed in the Olympiads of Ancient Greece, where sports exhibitions walked in equality with artistic exhibitions.”

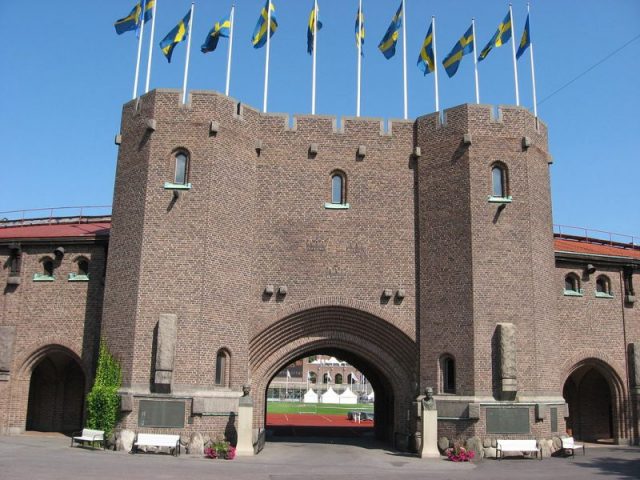

By 1912, the Baron had successfully secured his dream and the first Olympics for art were held at the Stockholm Summer Games. There were five categories that could be entered, and all entries had to be related to sport in some way.

The categories were: architecture, music, painting, sculpture and literature. The medal system worked in the same way as the physical sports with a gold, silver and bronze for each category.

Unfortunately, the caveat that all the art had to be sports based, and the fact there had to be a competition at all, meant that the art games were met with distrust from large factions of the art world.

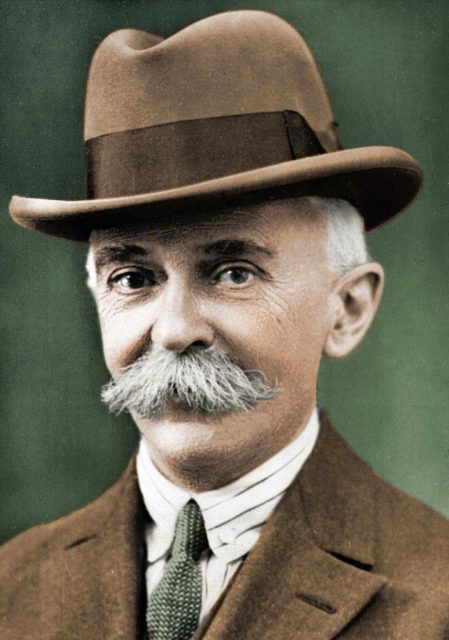

In the first art games, Baron Pierre de Coubertin entered his peom “Ode to Sport” under the pseudonyms George Hohrod and Martin Eschbach and won the Olympic gold for literature — whether his true identity was discovered during deliberations or whether his Ode really was a gold standard we will never know.

Over the decades, as the Olympics was becoming the behemoth that is it today, the art categories became less popular with artists who didn’t see the merit in competing and did not find any joy in creating artworks that were entirely sports-inspired.

The judges did not seem overly enthusiastic about the process either, as the Smithsonian reports “the format of the competitions was inconsistent and occasionally chaotic: a category might garner a silver medal, but no gold or the jury might be so disappointed in the submissions that it awarded no medals at all.”

The crowds, however, seemed to love the art spectacle and would turn out in large numbers to view the entrants. At the 1932 L.A. Summer Olympics, a record 400,000 people turned out to see the art games exhibits at the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science and Art.

For the 1948 Olympics, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), after much argument, voted to scrap the art based Olympic categories and replace them with a non-competition-based exhibition called the Cultural Olympiad.

The decision meant that all 151 medals that had been awarded in the previous three decades were made void. One of the final winners of the art Olympics was John Copley of Great Britain; at the time of winning he was 73-years-old and would have been the oldest Olympian on record if his victory had been allowed to stand.

The spirit of Baron Pierre de Coubertin and indeed, the spirit of the original Olympics, is remembered to this day in the IOC commissioned Sport and Art contest which is held before the start of each summer Olympics.

Read another story from us: Roman Emperor Nero Competed in the Olympics

There are no medals on the table, but entrants can win cash prizes and the chance to be exhibited in London during the Games.