The German city of Münster in the province of North Rhine-Westphalia, today a peaceful university town, was the focus of a turbulent chapter in history, namely the brutal Anabaptist rebellion.

St. Lamberti Church, located on the Prinzipalmarkt, is adorned with a rather strange set of ornaments.

For almost 500 years, three man-sized iron cages have been left hanging from the church spire as a reminder of the disobedience of the 16th century rebels.

The cages that once held the mutilated and tortured bodies of three rebel leaders now hang empty, still provoking debate among the citizens, not all of whom agree that this symbol of torture should be displayed in their town.

In 1530, Münster was a town divided between Catholic aristocracy and the disenfranchised peasants, poor and reformist.

At the head of the later was Bernhard Rothman, an evangelical Protestant who had drawn a large following among the angry citizens of the town who had felt that their rights were not respected.

The rising numbers of rebels threatened the position of the Catholic Church and its hegemony. That alarmed the prince-bishop, Franz von Waldeck, who tried to expel the reformists and their leader from the town.

However, under the pressure of Rothman’s followers, the city council did not allow for it. On February 14, 1533, the council of Münster granted the religious freedom to all groups in the town.

Jan Matthijs, an Anabaptist preacher from Leiden in the Netherlands, figured this treaty of religious tolerance would make Münster the perfect place for him to establish his reformist utopia.

The Anabaptist sect, or “rebaptizers” were widely persecuted for their belief that only willing baptism as an adult would allow a person to enter the kingdom of heaven. Their children were thus not baptized, a concept that was feared and even viewed as heretical by many.

One of the central tenets of Anabaptism that Jan upheld was social equality. Alongside his idea to ban private property and money and establish a sort of pure communism was another controversial belief that did not sit well with the pious Catholics and Lutheran Protestants. Allegedly, Jan of Leiden was a proponent of polygamy.

However, on arriving in Münster, Jan of Leiden and his followers were welcomed by Rothman, who embraced their radical ideals.

It did not take long for Jan to style himself as king of what soon became known as the “New Jerusalem,” preaching that the Second Coming of Jesus Christ would happen that coming Easter and leading a rebellion against Catholic rule. The city council was taken over by fanatical Anabaptist believers.

In a rapid turnaround of the status quo, Jan’s rousing calls to execute those who refused to be rebaptized led to many Catholics and Lutherans fleeing the city, as a flood of Anabaptists moved in. The rebels burned all books apart from the bible, and, according to The Local de, forced all women of marrying age to take a husband — Jan himself had 16 wives. Corporal punishment was meted out freely for trivial offences against the new hierarchy.

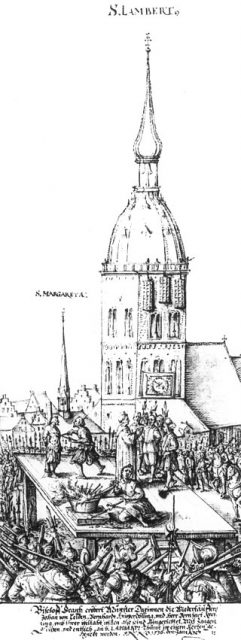

In a bid to put an end to this anarchistic religious fervor and regain Catholic control over Münster, Bishop von Waldeck gathered a mercenary army and laid siege to the city.

The city was finally broken on the night of June 25, 1535. Aided by a captured Anabaptist deserter, von Waldeck’s army entered through the main gate and recaptured Münster. Jan of Leiden and his two closest followers, Bernd Knipperdollink and Bernd Knechting, were imprisoned and tortured using various techniques.

They were repeatedly burned with hot tongs before being killed. As reported by German Girl in America “the Spanish Inquisition learned from and used these German Torture techniques.”

After the prisoners were killed, van Waldeck had the three iron cages made in order to display the mutilated bodies as a warning to any other would-be rebels. Their remains were left dangling from the tower for 50 years.

The bodies were a feast for ravens who frequented them on regular basis. According to Mental Floss, this scene prompted artists to draw numerous pictures and paintings of it.

After the bodies were removed, the cages were left on the spire. In 1800 the original tower was demolished and rebuilt — and the cages were put back in the place.

During World War II, Münster was a target for British bombing raids. St. Lamberti Church received a direct hit that caused the cages to come crashing down. Four years later the church was rebuilt, and the repaired cages put back in their original place.

The cages were and still are a topic of debate on religious tolerance, as they are seen as a symbol of tyranny and aggression.

In 1987, the church installed light bulbs, serving as a replacement for candles, which burn from dusk till dawn “in memory of their departed souls.”

St. Lamberti Church in Münster is interesting because of an additional and unrelated reason. It is the only church in Münster to have a Türmerin, or door-watcher. The solitary post is currently held by Martje Saljé, Münster’s first female Türmerin.

Read another story from us: The Mysteries and Ghosts Surrounding Ireland’s Most Haunted Castle

Her role is to ring the church bells and watch over the town from this high point. Additionally, she lives in the tower.