The Bayeux Tapestry is a medieval textile that dates from the 11th century and depicts the Norman Conquest over England.

But what was its purpose and significance, besides simply being a pictorial chronology of historic events?

Measuring an astonishing 231 feet (70m) long and 19.5 inches (49.5cm) high, the tapestry is actually an embroidered cloth and not a tapestry per se.

It is embroidered with crewel or worsteds (a high-quality wool yarn) in only eight colors, with 75 individual scenes.

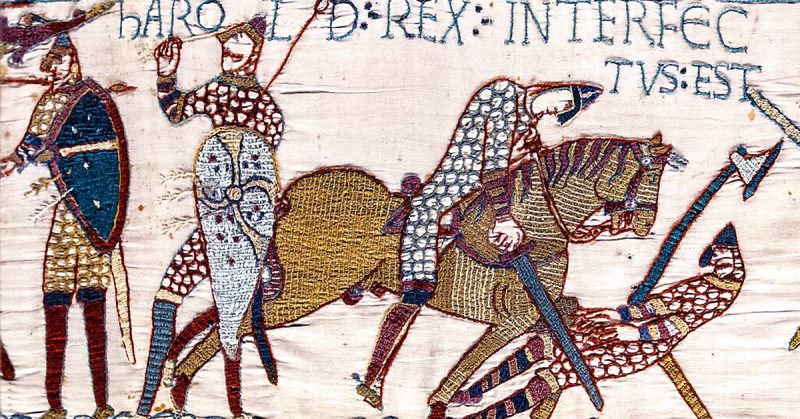

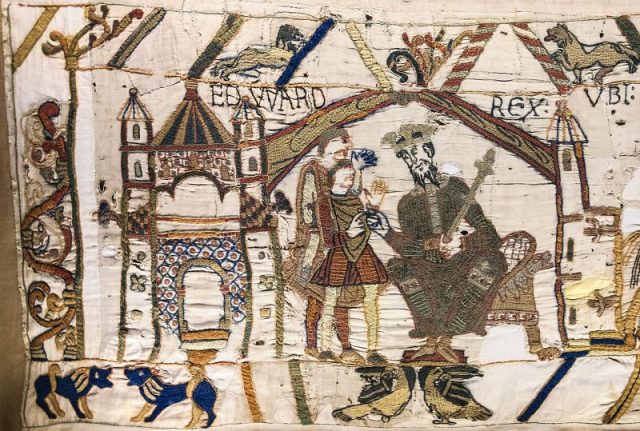

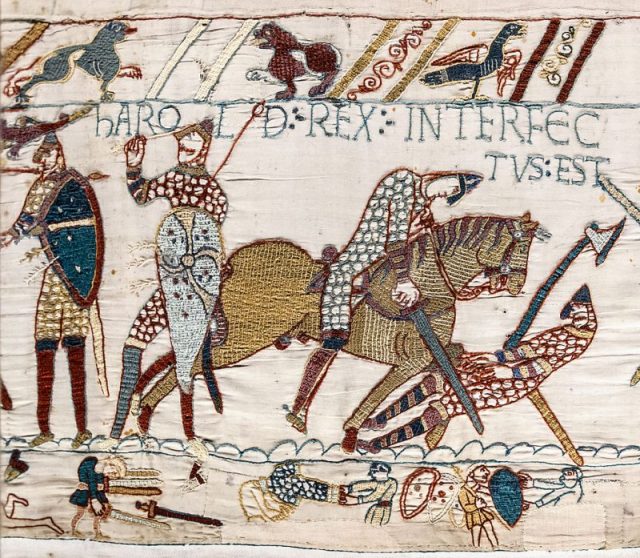

Playing out much like a modern comic book, each scene includes Latin inscriptions, or tituli, which describe the events leading up to the famous Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066.

The panels would have been produced separately in nine easier to manage sections and were then stitched together to form one long unit. While the first reference to the extraordinary work doesn’t appear until 1476, the tapestry is believed to date from the 1070s, and was completed in time for display at the dedication of the newly finished Bayeux Cathedral in France in 1077.

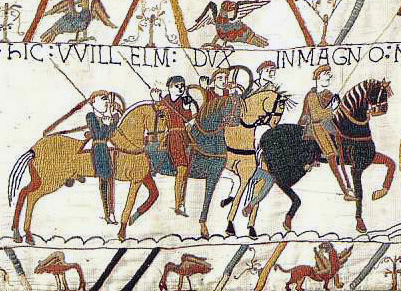

Believed to have been commissioned either by William the Conqueror’s half-brother, Bishop Odo, or Queen Matilda, his wife, the cloth is known in France as “La Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde.”

It is likely that the design and fabrication was done in England by Anglo-Saxon embroiderers, who were probably all women. There are suggestions of Anglo-Saxon dialect in the Latin text, and the vegetable dyes used in the worsted can be found in cloth traditionally associated with England.

Howard B. Clark, author and director of The Medieval Trust, has suggested that the designer of the tapestry may have been the Abbot of St. Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury, since he had previously held a position as head of the scriptorium at Mont-Saint-Michel, which is well known for its illuminated manuscripts. The Mont also featured in a scene in the tapestry itself.

The scenes are embroidered using two methods: a straight stitch for outlining and for lettering, and a stitch called couching, or laid work, for filling in the figures. The design of the work features a wide central zone – the main content – with narrower borders along the top and bottom.

The eight colors used are natural: terracotta, blue-green, dull gold, blue, and olive green, as well as dark blue, sage green, and black.

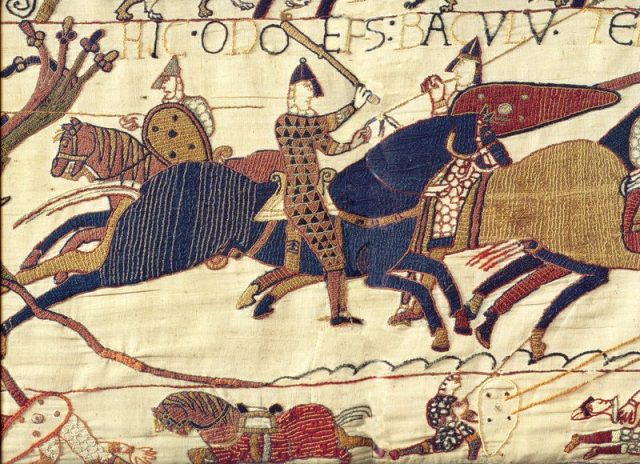

The action of the tapestry occurs in its central area where scenes are separated by beautifully rendered trees. It is here that we see images like the death of Edward the Confessor in January 1066, which provided the catalyst for the Norman Conquest.

Events continue through Harold Godwinson being crowned King of England (despite having previously pledged loyalty to William Duke of Normandy, later the Conqueror, although what exact promises were made we do not know), to the Normans leaving France and marching on Hastings.

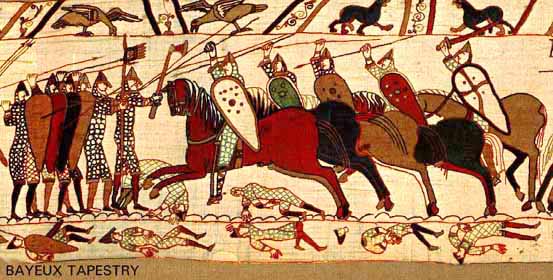

This is, of course, a simplified version; the tapestry features many interesting and intricate scenes. It is, instead of being a depiction simply of the Battle of Hastings, a portrayal of life in pre-Norman England, as well as a political commentary on events that led up to the famous battle.

The details in the embroidery and its scenes are extraordinary. As Sylvette Lemagnen stated in her 2005 book La Tapisserie de Bayeux: “The Bayeux tapestry is one of the supreme achievements of the Norman Romanesque…Its survival almost intact over nine centuries is little short of miraculous … Its exceptional length, the harmony and freshness of its colours, its exquisite workmanship, and the genius of its guiding spirit combine to make it endlessly fascinating.”

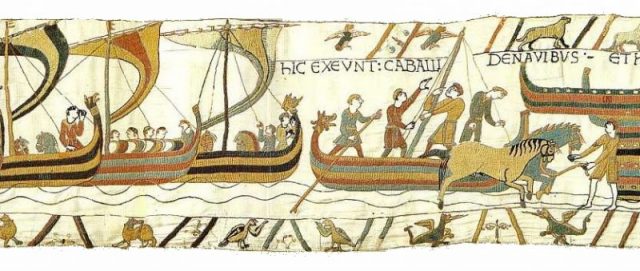

Scenes are varied and include such things as soldiers burning a house, a woman holding a boy’s hand as they flee or beg for mercy; horses being loaded on to ships, the fear in their eyes evident; meals being cooked and served; and even Haley’s Comet.

The tapestry also offers images of both Anglo-Saxon and Norman armor and weapons, including the differences between English and Norman shields, the use of archers and, interestingly, stirrups. Indeed, military historians have used the tapestry to learn more about the specific armaments carried by both sides, as well as techniques employed during the battle.

The Latin text provides the viewer with a running commentary on events and what is happening, as well as a “who’s who” throughout the piece.

The text is brief but provides enough information to figure out what is occurring in each scene. The text uses many abbreviations — not uncommon in Latin — and personal names are not Latinised, nor are place names, showing an English influence in several areas, which again leads to the notion that the tapestry was embroidered in England.

The tapestry culminates with Harold famously taking an arrow to the eye and dying on the battlefield. The English retreated, having been routed, and the Normans declared victory, both on the field and over Anglo-Saxon Britain.

The end of the tapestry, however, is missing or was never completed. French historian Lucien Musset suggested that the last panel that we see today was added around 1814, when anti-English sentiment was high in France.

The Bayeux Tapestry is an extraordinary work, not only for its overall age, excellent condition, and depiction of the Battle of Hastings, but also as a primary source for Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norman society, culture, and history.

It was on display in Bayeux Cathedral when it was initially finished and stayed there from 1476 onwards, although its whereabouts in between are unknown. Today, the tapestry resides permanently in its own museum in Bayeux, a short distance from the cathedral in which it made is debut.

Read another story from us: Man Arrested for Attacking and Trying to Steal the Magna Carta

It is scheduled to leave France in 2022, however, while the museum undergoes refurbishment and will return to the UK for the first time in almost 950 years to go on display at an as yet undisclosed location.