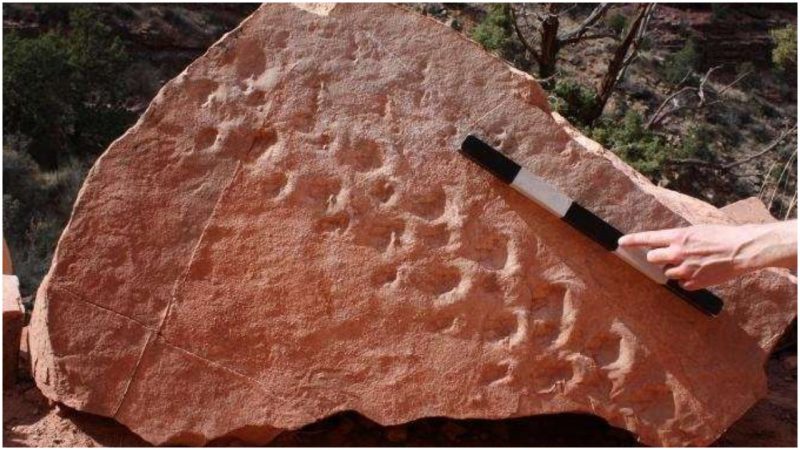

Over three hundred million years ago, a lizard-like reptilian ran across wet sand in the Grand Canyon in Arizona.

Twenty-eight of its footprints have recently been discovered after a rock fell and split open on the Bright Angel Trail.

The first to see the prints was a group of paleontology students who notified Stephen Rowland of the University of Nevada in Las Vegas.

Rowland and geologist Mario Caputo, from California’s San Diego State University, traveled to the Grand Canyon to study the footprints for themselves. They found the footprints traveled in a side-stepping manner rather than straight forward.

Similar tracks have been discovered in Scotland and are estimated to have been left at about the same time as the tracks in Arizona — about 310 million years ago. These are now believed to be the oldest fossil evidence of a four legged land-dwelling animal in the Grand Canyon.

Fossils in the Grand Canyon are nothing new, but most are of aquatic creatures, bugs, or plant life. Other fossils are found occasionally as well. In March of 1927, according to nps.gov, a ranger at the park, G.F. Sturdevant, delivered several stones to Washington, D.C. containing tracks of an ancient lizard believed to be thirty-five million years old. At the time, dating rocks wasn’t nearly as precise as it is now, and it is possible they could have been much older.

The park is full of crinoid and brachiopod shell fossils as well as the footprints of centipedes and scorpions from about 120 million years ago. Impressions left by leaves, horsetail plants and ginkgo trees are found in the Hermit Shale, a layer of rock in the Canyon.

Stromatolites, which resemble pieces of wood, were formed over one hundred thousand years ago from bacteria layering with sediment in the shallow briny waters.

There are many caves and mine shafts that contain unearthed fossils and bones, but most are closed to the public because of previous tourist damage. The skeleton of a sloth that lived eleven thousand years ago, as well as the bones and eggshells of Condor birds, have been found in caves, and trace fossils such as shell imprints or bug tracks are common almost everywhere.

The oldest exposed rock formation in the Grand Canyon is Elves Chasm, which formed over 1.5 billion years ago. It forms part of the deepest layer, known as the Vishnu Basement Rocks. On top of these ancient igneous and metamorphic rocks, sediment layed down over millions of years has slowly transformed into the beautiful layers of sandstone that form the uppermost two thirds of the canyon.

515 million years ago, the canyon was under a shallow sea of muddy, high saline water as shale formed. About three million years later, the water had dried into streams crossing plains where dragonflies, other insects, and reptiles lived among grasses and ferns as the red sandstone mixed with silt and mud.

Even more sandstone appeared several million years later, in which another lighter colored layer was made. The most recent layer began around two hundred seventy million years ago.

According to the National Park Service, the continents had not yet broken into the separate formations we know today, and a clear, shallow sea with crinoids, corals, sea sponges, fish and sharks swam together in the Canyon.

Eventually, the seas and rivers became one river winding its way through the area, eroding millions of years worth of silt, limestone, sandstone, shale, and granite to create the chasm we see today.

The National Park Service frowns upon visitors digging up, removing, or even relocating fossils and will prosecute anyone found doing these things.

They welcome tourists to take pictures or rub the rocks in which the fossils were found and will happily identify any of them.