New light has been cast on the origins of Count Dracula, thanks to a team at the local library where he did his research.

“This is a very exciting discovery,” commented Prof. Nick Groom (Exeter University) on the website of the London Library. According to him, the news shows “The London Library was the crucible of one of the most influential novels in world history.”

Located in St James’s Square, the library has a reported 17 miles’ worth of shelves. It is here that author Bram Stoker came to browse the collection of over a million books and periodicals.

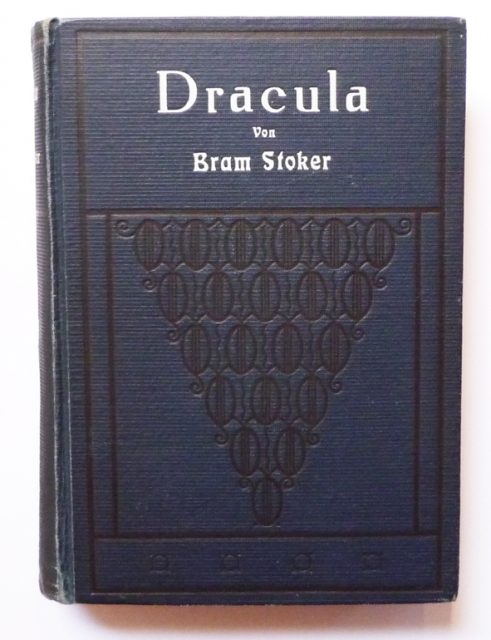

At that time he worked as a manager at the famous Lyceum Theatre. For Stoker, writing was a sideline, though that would change once Dracula was published.

While something is known about the places that inspired the book, such as Whitby in North Yorkshire where part of the tale was set, the creative process that shaped the iconic vampire himself was more mysterious.

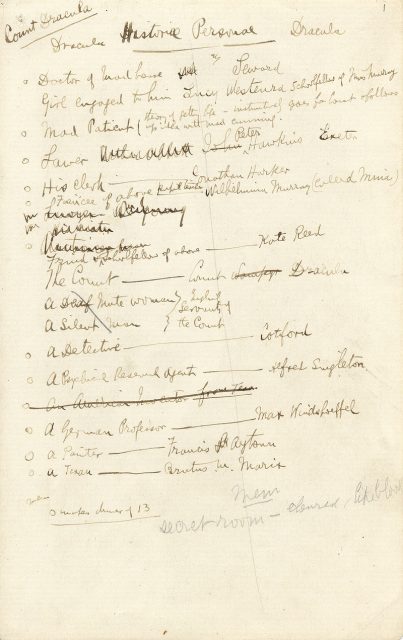

Now Development Director Philip Spedding has revealed an official connection between the birth of Dracula and the London Library. The truth was buried within Stoker’s documents, in a selection of notes made whilst compiling his thoughts.

These were auctioned off by Stoker’s widow Florence in 1913, the year following his death. After going to a museum in Philapdelphia, they were examined and published in 2008 by Robert Eighteen-Bisang and Elizabeth Miller.

The precious scribblings and typed sections gave people an insight into Stoker’s mind, as he took inspiration from worldwide folklore.

As previously discovered, the Dracula writer was a member of the library for 7 years, which was the time it took to write his Gothic masterpiece.

Endorsing that membership was bestselling author Henry Hall Caine, to whom Stoker dedicated the novel. Strong ties indeed, however this most recent find explicitly ties the London Library to the invention of the world’s best-known vampire.

Around 30 texts in all were used to research Dracula, with 25 of them found on the shelves. Spedding and company were thrilled to realize they were handling books the writer himself would have read in preparation for the Count’s creation.

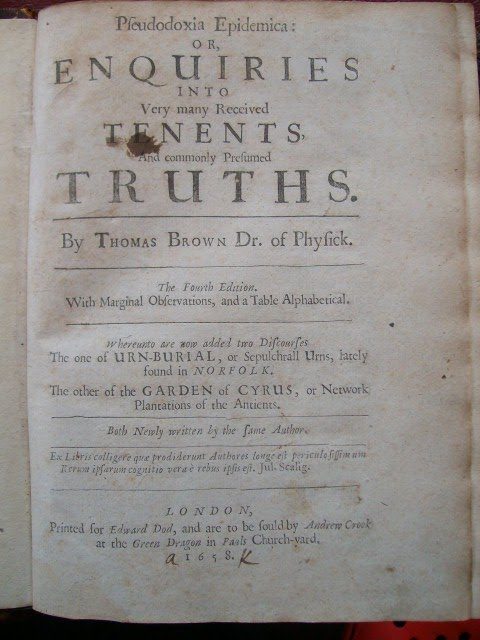

Stoker had even marked the pages of the books, which included “Sabine Baring-Gould’s Book of Were-Wolves and Thomas Browne’s Pseudodoxica Epidemica. But the range of titles also sheds light on the detail of Stoker’s geographical and historical research – for example, AF Crosse’s Round About the Carpathians and Charles’ Boner’s Transylvania.”

Pseudodoxica Epidemica is a key title, as the library’s 17th century copy was a present given in 1937 by Stoker’s son, N.T. Stoker.

But of even greater interest was his other gift, The Land Beyond The Forest by Emily Gerard (1888). This was Bram Stoker’s own copy of the novel, and it had a major influence on the Count’s character.

As mentioned on the BBC News website, it “is credited with introducing Stoker to the concept of ‘nosferatu,’ a vampire-like creature who sucks the blood of innocent victims. She wrote her book after spending two years in the mid-1880s in Romania with her husband, who was posted there as an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army.”

Quoting from the text, the article writes that a victim becomes “a vampire after death, and will continue to suck the blood of other innocent persons till the spirit has been exorcized by opening the grave of the suspected person, and either driving a stake through the corpse or in very obstinate cases of vampirism it is recommended to cut off the head, and replace it in the coffin with the mouth filled with garlic.”

And so were born Dracula’s diabolical activities. Yet out of these dark deeds, it’s hoped something good will come.

The London Library has counted among its members the likes of Stoker, as well as William Makepeace Thackeray and T.S. Eliot. Director Philip Marshall believes the shelves hold invaluable reference points for up and coming writers.

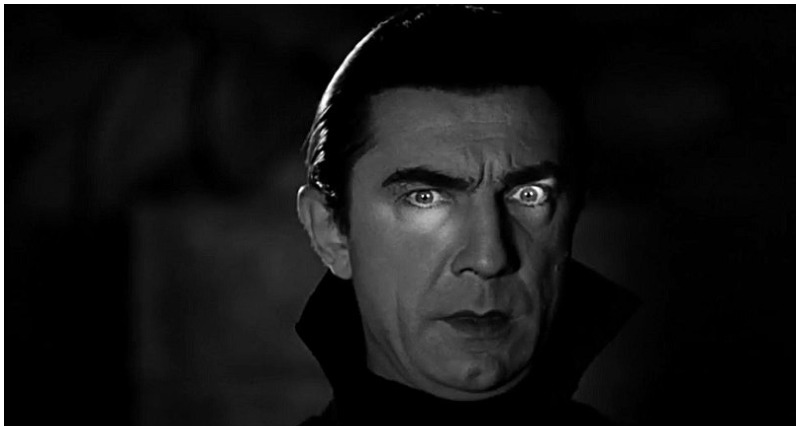

Read another story from us: Christopher Lee – The Man Who Embodied Dracula

Writing on the library site he encourages them to “follow Bram Stoker’s example and use The London Library as a source of inspiration and support when creating their own masterpieces.”