Beautiful. Immature. Fashionable. Jealous. Tempestuous. Unstable. Stupid.

Just a few of the adjectives that have been used to describe Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg (1599-1655), a German princess who became queen consort of Sweden. Hers was a life that was equal parts melodrama, tragedy, mystery, and adventure, with a bit of unintentional comedy mixed in for good measure.

This was a woman who adored her husband, Gustavus Adolphus, the King of Sweden; despised (for a time, anyway) her young daughter Christina — who would come to inherit the throne — to such a degree that many believe she tried to engineer her demise; and, basically, sent no less than three countries into turmoil with her mercurial personality and entitled demands.

This incredible story would unfold in 1616, when the 22-year-old Gustavus Adolphus, soon to be the Swedish king, was looking for a Protestant bride.

He had heard reports of the beautiful, intelligent 17-year-old princess Maria Eleonora, daughter of John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg, and Anna, Duchess of Prussia.

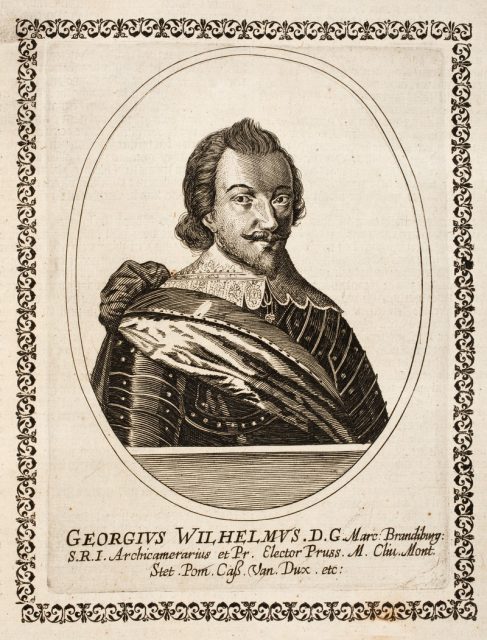

But not everyone was in favor of the union, particularly the princess’s brother, George William, Duke of Prussia, who feared it would lead to conflicts with neighboring Poland, which was at odds with Sweden at the time. He wrote to Gustavus Adolphus to refuse his consent.

No matter. Gustavus Adolphus would not be deterred, and in 1620 he traveled to Berlin to plead his case — in secret — with the Duchess and her daughter. Soon, the Electress Dowager was conducting marriage negotiations, after which, a jubilant Gustavus Adolphus returned to his home turf to prepare for his bride-to-be.

George William, who had just succeeded his father, was dumbfounded upon learning of his mother’s scheming. But despite his protests, Maria Eleonora was smuggled onto a Swedish ship, which took her to Stockholm. Weeks later, the couple married.

Things went smoothly at first. Foreign ambassadors found the new queen charming and applauded her exquisite taste. But there were signs of trouble. For one thing, Maria Eleonora hated Stockholm, considering it an uncultured country lacking the excitement of Berlin.

She had trouble warming up to the Swedish people, as well as the frigid climate. Still, she tried to find ways to adapt, creating her own entertainment (she frequently brought buffoons and dwarfs to court). Goldsmiths, musicians, and ballet dancers were also brought from Germany and France.

What’s more, Maria Eleonora was moody, prone to outbursts of salty language, oftentimes directed at her husband, the king. Still, she was very much in love with her husband. Unfortunately, Gustavus Adolpus was away for much of the time, taking part in military campaigns.

Maria Eleonora responded to his frequent absences by sinking into a deep depression, often refusing to eat and sleep. With the king so frequently risking his life in battle, it became imperative that his wife produce a male heir to the throne. Within six months of their marriage, Maria Eleonora gave birth to a stillborn daughter. Two years later, she became pregnant with another daughter, but the baby died at eleven months. In May of 1625, she gave birth a third time (to a boy), but he too was stillborn.

In 1626, during a rare break in battle, Gustavus Adolphus returned to Stockholm. Shortly thereafter, on December 7th, Maria Eleonora gave birth for the fourth time. The baby was healthy, though had fleece lanugo (a condition where soft, downy, unpigmented hair covers the body of a newborn). In this case, the infant was enveloped from its head to its knees, leaving only its face, arms and lower legs visible.

At first, it was assumed that the baby was a boy, but upon closer inspection, it became clear: It was a little girl. Gustavus Adolphus’ half-sister Catherine, afraid of the king’s reaction, carried the baby to him “in a condition for him to see and to realize for himself what she dared not tell him.”

She needn’t have worried. Unlike England’s testosterone-mad Henry VIII, Gustavus Adolphus took the baby’s sex in his stride, remarking, “She is going to be clever, for she has taken us all in.” He decided to call her Christina, after his mother, and ordered that her arrival be announced with all the pageantry accorded to that of a male heir. His wife, however, would have a different reaction.

The court waited several days before breaking the “It’s a girl!” news. Upon learning the truth, Maria Eleonora shouted, “Instead of a son, I am given a daughter, dark and ugly, with a great nose and black eyes. Take her from me, I will not have such a monster!”

Shocking, to be sure. And then, peculiar things began to happen. A beam from the ceiling mysteriously fell on the cradle, coming close to crushing the infant. Another time, the little girl toppled down a flight of stairs.

A nursemaid was blamed for dropping the baby onto a stone floor, resulting in an injury that would leave Christina with a crooked shoulder for the rest of her life. Gustavus Adolphus would describe his wife as being “a very sick woman.”

So much so that he wouldn’t allow her to have much of a say in their daughter’s upbringing. Instead, the princess was placed in the care of his half-sister Catherine. Gustavus Adolpus himself was determined to raise Christina as he would a boy, taking her to military reviews, teaching her to ride, shoot, and hunt. Soon, she was swearing a blue streak and even appreciated a good dirty joke.

Meanwhile, Maria Eleonora’s husband’s life was constantly in danger on the battlefield. After years of pleading, she was allowed to be with him in Germany, moving into Wolgast Castle. Two years later, in the Battle of Lützen, the 37-year-old Adolphus was shot in the back and dragged by his horse. He managed to free himself, but was killed by another shot through his head.

In 1633 Maria Eleonora returned to Sweden with her beloved’s embalmed body. She refused to bury Gustavus’ body for more than a year and forced Christina to live in seclusion in rooms draped in funereal black, blocking out the light of day.

Even more bizarre: A golden casket, containing her husband’s heart, was hung over her daughter’s bed. Little wonder, Christina became seriously ill; a painful ulcer appearing on her left breast.

It was decided that Maria would not be a part of the regency government while her daughter Christina was a minor. Her dicey state of mind might have been a factor, but there were other reasons for her exclusion.

For one thing, Maria Eleonora was getting a little too friendly with the Danish — at the time enemies of Sweden — and even pronounced herself open to a potential marriage between Christina and Danish prince Ulrik. The royal court, very nervous about this wild card in their midst, started monitoring her every move.

In 1636 Maria Eleonora lost her parental rights. At this point, she wanted to return home to Brandenburg. When the Swedish government vetoed a visit, Maria Eleonora took things into her own hands. She reached out to Danish King Christian IV and began plotting a secret escape.

In 1640 the queen, dressed in disguise, left Gripsholm Castle and hopped on a Danish ship. The plan was for the crew to bring Marie Eleanora to Brandenburg, but she persuaded the captain to deliver her to Denmark instead.

King Christian was less than thrilled with his surprise guest, but was stuck with her, since George William refused to receive his sister. Maria Eleonora had to wait until his death in December of that year to enter Germany. But there was a catch: The new Elector insisted that Sweden provide for her upkeep. The teenage Christina would negotiate a pension, adding to it from her own purse.

Alas, in time, Maria Eleonora began to miss Sweden, and in 1648, Queen Christina, now aged 22 — ever the good and dutiful daughter — made arrangements for her mother to return to Stockholm. She went to meet the ship, and when its arrival was delayed, camped outside for two nights, falling ill in the process.

In 1650, Marie Eleonora attended her daughter’s coronation. Christina bought a castle for her, close to her own royal residence in Stockholm.

Four years later, Christina would abdicate her throne to her cousin Charles Gustav. She offered an array of explanations: a man was better suited to rule the Swedish army, she was exhausted by her many duties and needed a rest. What she failed to mention was her recent conversion to Roman Catholicism, which was banned in Lutheran Sweden.

Read another story from us: Queen Alexandra’s Missing Dress Found in an Attic

Marie Eleonora’s main concern was how the abdication would affect, well, Maria Eleonora — or, more specifically, her finances. No worries, Christina and Charles assured her. The Queen Dowager was provided for until her death in 1655. She was laid to rest in the Riddarholm Church, in peace at last, beside her husband and two of their children.