The first Christmas during World War I, in 1914, came just five months into a horrendous war that four years later concluded with an unprecedented death toll of over 16 million people.

On December 7th that year, the newly-elected Pope Benedict XV called for a Truce of God, in which fighting would come to a halt over the Christmas period.

The Pope’s bid was quickly dismissed by military commanders, but regardless, guns did fall silent in some areas of the Western Front where British and French soldiers were confronting the German Army.

There were soldiers who indeed settled for a more festive holiday period, and their move today is remembered as the Christmas Truce of 1914.

The public has ever since been more than eager to romanticize this occurrence, thinking that at least for a short instance of time, the ceasefire was attended by everyone from the two sides, with British and German soldiers even playing a friendly match of soccer.

It was not exactly like that in reality, but for the roughly 100,000 soldiers who opted-in, Christmas was convenient enough time for a break.

The feeling must have been mutual, on both sides of the battlefield, and aided by months of nasty lifestyle in the damp-filled and cold trenches.

Many of the soldiers also clung to the hope that they would return home by Christmas.

Historians have never truly agreed on the details about the Christmas Truce, but it’s generally accepted there was one key factor that led to such development.

In some areas of the Western Front, enemy trenches were very close, close enough for soldiers to be able to hear each other talking.

Such proximity enabled some of them to adopt a “live and let live” kind of attitude, in which there would be days — even well before Christmas — that would pass without any gunfire.

And for Christmas: some likely moments include lighting candles and singing carols on Christmas Eve.

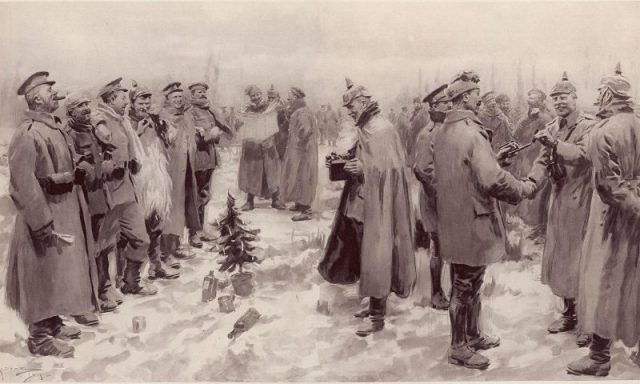

The carols were sung in English, Latin, and German. Then, as soon as dawn broke on Christmas Day, unarmed soldiers stepped out from the trenches and — although still enemies — they met on the area designated as No Man’s Land, wishing each other Merry Christmas.

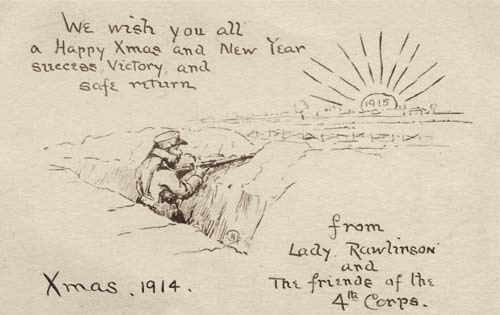

The mood for the moment was slightly improved because both sides had received letters or gift boxes sent from home.

In fact, on the British side, King George V had taken care to send gift boxes to each and every soldier fighting on the front. Some of the packed items included pens, paper, and tobacco, writes the BBC.

The soldiers mingled with their foe on No Man’s Land, with warming, brotherly scenes like exchanging gifts or taking a photo. Even more amazingly: “one account mentions a British soldier having his hair cut by his pre-war German barber; other talks of a pig roast.”

“Several mention impromptu kick-abouts with makeshift soccer balls, although, contrary to popular legend, it seems unlikely that there were any organized matches,” writes Time.

Other than enjoying such brief moments of little freedoms, the need to cease the gunfire would have also been one of practical nature.

Prior the holidays, heavy bombardment on some sections had resulted in numerous casualties.

The corpses of fallen soldiers had lain unattended for days or weeks. This was an opportunity to collect those bodies and give them a proper burial — at least one without enemy bullets flying overhead.

Silence did not prevail everywhere along the front. Unrest continued in places such as the West Flemish Front, a section of the Western front defended by Belgian troops.

Away from the trenches, German warships were battering British seaside towns such as Whitby, Scarborough, and Hartlepool, according to the BBC.

Those naval attacks resulted in hundreds of civilian casualties for Christmas.

So, when reports reached the higher ranks that different forms of truce had occurred on the frontlines, including friendly interactions with the enemy, the reaction was of anger.

So much so that the unofficial Christmas Truce of 1914 would be the very last of its kind.

Officers were clearly instructed that they remain watchful for the remainder of the conflict and make sure similar scenes did not repeat ever again.

Any such incident was to be regarded as treason.

Over a century later, the Christmas Truce of 1914 has never failed to inspire. It describes a moment of peace in a calamitous and costly war. In the context of war, such festive mood among soldiers may have justifiably worried officials, perhaps in fear of a possible mutiny.

It would have also, at best, confused compatriots who kept on fighting the enemy despite it being a special time of year.

Read another story from us: Clear Coke was Given to a Soviet General to Make it Look Like Vodka

Sadly enough, at the end of 1914, the conflict was only just beginning to form its really gruesome character. The New Year brought bigger atrocities, so the Christmas Truce, where it happened, was nothing more than a little calm before the real storm.

But still, that brief moment of calm was important, for it communicated that fighting men still had one genuinely most human wish — that there is peace.