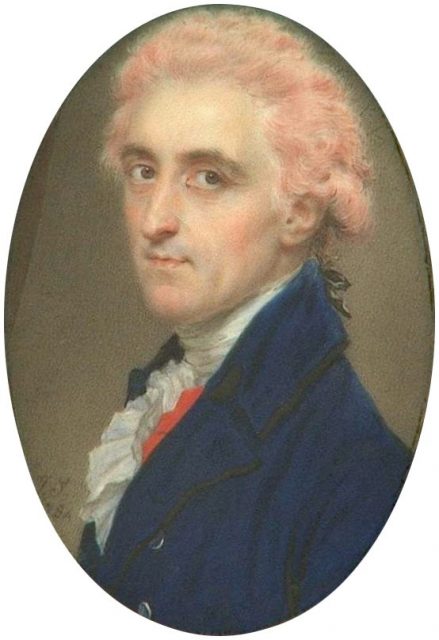

Fashion has always been a is a harbinger of the times. Take the 18th century, for example. Never — certainly not in European history — have people been quite so excessively and boastfully, well, fake.

Extravagant hairstyles, particularly towering powdered wigs, abounded. But that would change. As the 18th century came to a close, wigs (for both men and women) were on their way out, seen as a sign of deception and viewed with suspicion.

During the French Revolution, people — particularly aristocrats — fearful of being targeted, imprisoned, and worse, stopped wearing elaborate powdered toppers, opting to go au naturel.

At the turn of the century, a time of more restraint, the trend continued. Women’s hair once again saw the light of day, held in place with tortoiseshell combs, colorful ribbons, or pins.

Though some continued to use clip-in hairpieces (or postiches, as the French called them) for much of the nineteenth century, artifice was something to be avoided.

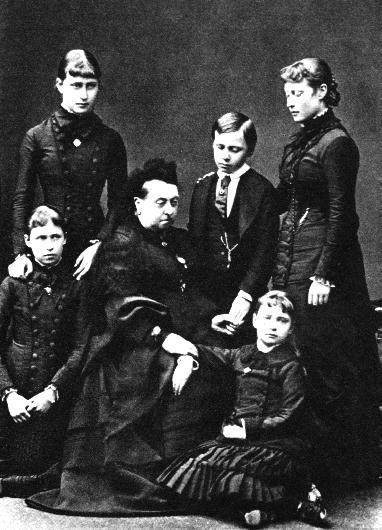

Indeed, a letter sent to Queen Victoria from her aunt Queen Adelaide in 1843 perfectly illustrates the disapproval people had regarding wigs at the time.

In the missive, an opinionated Adelaide declares how unfortunate it is that Victoria’s eldest daughter is forced to wear a powdered wig. How strange she must look, clucks Adelaide.

For men, wigs were considered the height of vanity. Women wearing wigs would be accused of employing trickery in a desperate bid to snare a husband. Wig became such a forbidden word that hairdressers came up with colorful euphemisms, such as “gentlemen’s invisible perukes” or “ladies’ imperceptible hair coverings.”

Often, being fitted for a wig was a clandestine encounter between hairdressers and their clients. In his book The Strange Story of False Hair, author John Woodforde relays a touching story about a girl, whose mother shaved her head and fitted her with a blonde wig to lure potential suitors.

After marrying, the girl would wear the wig till the day she died. She would go so far as to issue orders specifying that if she should die before her husband, her hairdresser should style the wig in her coffin, lest her husband discovers her shameful secret.

Frankly, many were happy to be free of their faux hair. The heavy, elaborate wigs of the Georgian era were something of a health hazard. People developed sores on their scalps, suffered from lice, and ran the risk of their hairpieces exploding! (The animal fats used for styling were highly combustible.)

Those still wearing full wigs by the mid-19th century often did so for reasons beyond the superficial.

A woman suffering from baldness, for example, was probably afflicted with syphilitics — a bacterial infection which caused symptoms such as open sores, nasty rashes, and bald patches.

Women’s hair during the first part of the century was typically worn in a neoclassical style that harkened back to ancient Greece, tied in a knot or chignon at the nape of the neck, curls framing the face and forehead, and accessorized with ribbons and headbands.

In later decades, hair became a bit more elaborate, perhaps swept upward and adorned with combs, flowers, leaves, pearls, or jeweled ribbons.

To create this style, women incorporated hairpieces made from strands collected from their combs and brushes and saved over time in ceramic or porcelain containers.

Men favored longer hair and mustaches, sideburns, and beards, during much of the 1800s — some using waxes and wood frames at the night to help preserve their shape.

In fact, the mid- to late-19th century would usher in more than a few advances in hair maintenance.

Eliza Rossana Gilbert, Countess of Landsfeld and a courtesan in the court of Ludwig I of Bavaria offered recipes for dying grey hair in an 1858 book she penned.

In 1882, Canadian Martha Matilda Harper started the first international chain of salons, offering a variety of treatments for healthy hair. And in 1890, Alexandre Godefroy invented a machine to dry hair in his Parisian salon.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the tide was turning once again, at least when it came to men, with publications such as the Hairdresser’s Weekly Journal suggesting that hairpieces created to hide male baldness went beyond mere vanity.

Read another story from us: Nipple Rings for Aristocrats – The Wild Victorian Fashion Trend

Women plagued with skimpy, wimpy strands weren’t quite as lucky.Intolerance toward faux tresses would continue all the way into the next century.