The American Revolutionary War was one of the most pivotal chapters in the histories of the great nations of the world. In declaring their independence from the British crown, the United States had effectively declared war on the most powerful country on Earth.

One of the more interesting chapters of this war was the occupation of New York by the British between 1776 and 1783.

History.com reports that many young sailors set out as privateers to harass the British Royal Navy during the war, with many of them eventually being captured and interned in British prison ships.

One such sailor was the young Christopher Hawkins whose recently recovered journal details his daring escape from the HMS Jersey prison ship.

Christopher Hawkins was only 13 when he signed up as a privateer aboard the brig Mariamne. Hoping to find his fortune, he eventually met with intense tribulation. American Heritage reports that the Mariamne was five days out of Newport when she was taken by two British frigates.

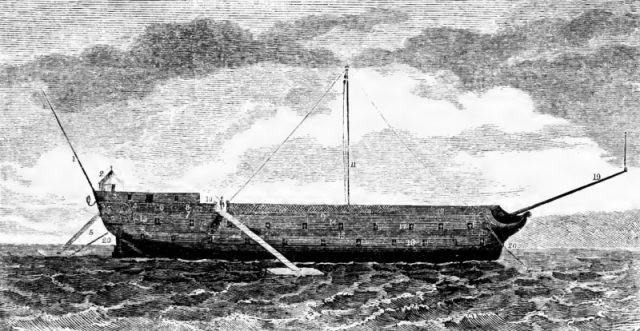

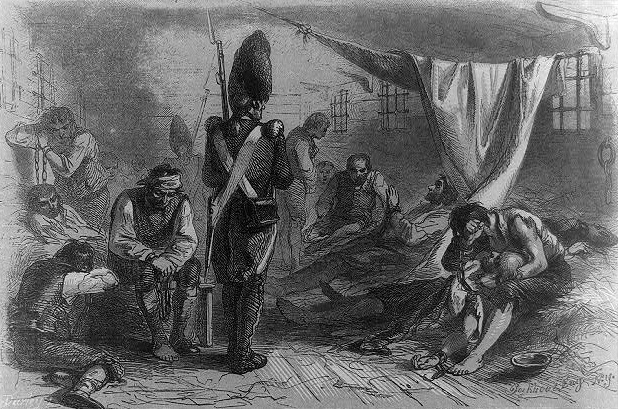

The crew of the Mariamne was taken aboard the HMS Jersey. Sickness and starvation were rampant, and death was very common among the inmates. Between six and eleven men died every day, mostly from diseases like dysentery or smallpox. The dead were carried up from below-deck every morning to be brought ashore and buried in shallow mass graves.

Getting enough food was a constant struggle. Hawkins’s journal describes one occasion when a prisoner had pilfered food from another group of prisoners. The offending prisoner was strapped to a water cask and allowed to be flogged by the other prisoners whose food he had stolen. The offender apparently fainted repeatedly during the flogging and died within days from his wounds.

With the stench of death all around him, Hawkins knew he had to do something fast or face the same untimely end as his fellow shipmates. Escape was a difficult venture since it would be extremely difficult to plan without other inmates knowing about it in advance of the attempt. The ship was also stationed in New York Harbor, surrounded for miles by British forces and loyalist Americans.

Although the prospect was daunting, escape was far from impossible. There were only about forty armed men on board at any given time, managing almost fourteen hundred prisoners. It wasn’t unheard of for a careless guard to get knocked out and allow twenty to thirty men to escape from the ship.

Hawkins’s journal details his escape from the hell of the HMS Jersey. Hawkins says that he stole an axe from the ship’s cook, which he used to break through a barred porthole during a thunderstorm.

In order to camouflage the sound of his axe against the bars, Hawkins timed his blows to be in sync with the thunderclaps. The cracking of the storm allowed him to break through the porthole without the sounds alerting the guards.

After escaping the hold of the ship, Hawkins had to swim for over two and a half hours. The surrounding countryside was mostly populated by loyalist Tories and it would be difficult for an escaped prisoner to find support from them.

Hawkins hid in barns for a couple of nights then decided to try stealing some potatoes from a field to stave off starvation. While attempting the theft, Hawkins was discovered by a young woman, who screamed and ran, forcing Hawkins to return to the woods in the opposite direction and arm himself with anything he could find.

Although fearful that the Tory hounds would be set on his trail, he proceeded unmolested and once again found a barn in which he slept upon a pile of flax.

The next day, Hawkins approached some young workers in a field, appealing to them for food and clothing. They introduced him to their mother who tearfully heard Hawkins’s story. She was kind enough to offer Hawkins some clothing and directions to a canoe which he could row across the small bay towards Sag Harbor.

Although Hawkins was apprehended once more in Oyster Bay, he escaped his captors before they could return him to the HMS Jersey. He eventually reached his home in Providence, Rhode Island. He later settled in Newport, New York, in 1791.

Read another story from us: Man Finds Rare 100-Year-Old Negatives – Uses Photoshop to “Develop” Them

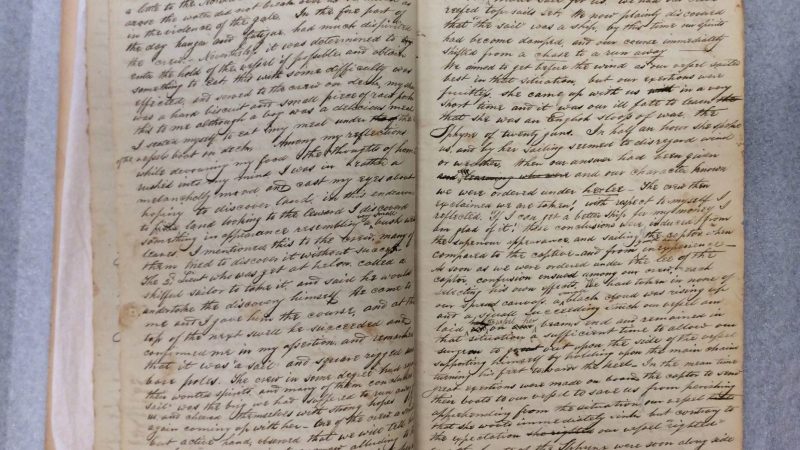

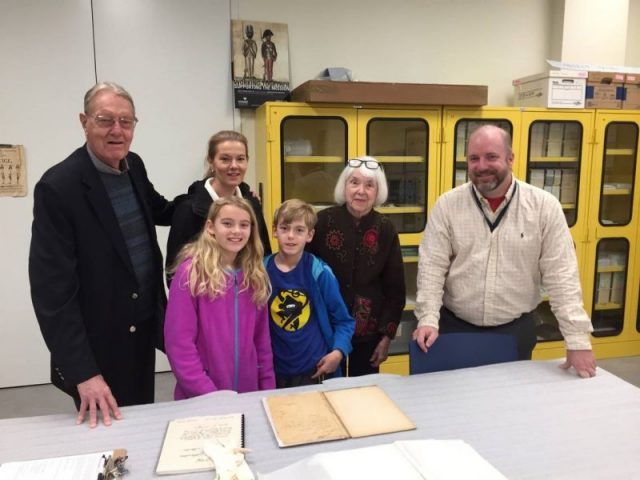

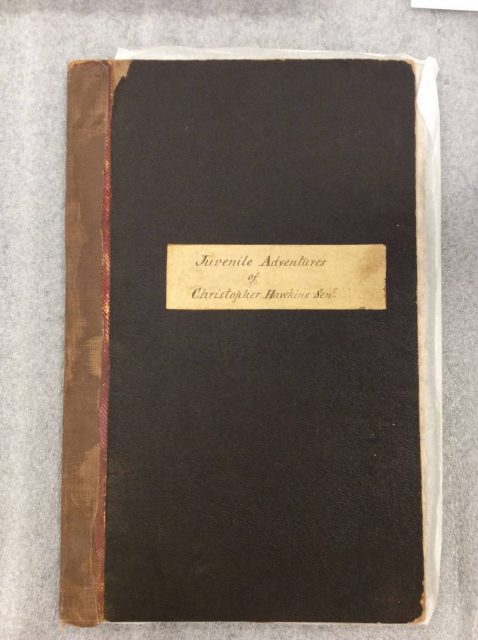

Hawkins wrote his memoir in 1834 at 70 years of age. The memoir was published in 1864 as the Juvenile Adventures of Christopher Hawkins. The original journal itself was eventually discovered in an old linen closet by Hawkins’s descendants who donated the find to the Museum of the American Revolution.