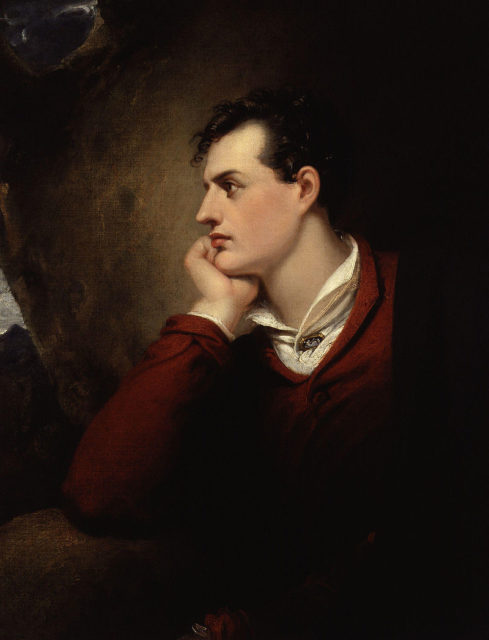

With a talent for writing poetry, a deformity to his right leg that affected his character, and an unstoppable appetite for women and debauchery, George Gordon Lord Byron stands out as an icon of the Romantic movement in literature.

He was born in London, in 1788 and his best-known work, widely read in schools to date, includes the Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

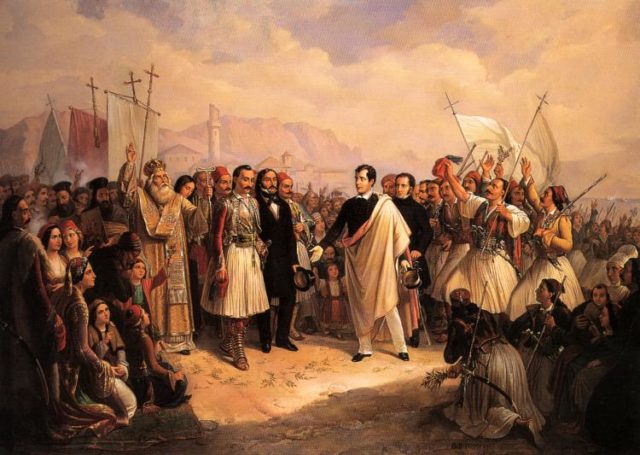

On the lesser known side of Byron’s life, he was as well involved in politics. He came from a well-off family, and his privileged position enabled him to serve terms in the House of Lords. But more notably, he actively participated in the Greek War of Independence to end the Ottoman rule there, offering both financial and logistical support. It would also be in Greece, the country which still praises him as a hero, where Lord Byron died in 1824.

Byron’s writing and political career began at quite an early age. He took up his seat in the House of Lords by the time he was 21, and was already past his first unreturned love from Marcy Chaworth — his cousin, who eventually inspired him to pen some of his early erotically-pumped poetry. He was also a student at Cambridge, but better remembered for taking a keen interest in gambling and sex.

At 22, Byron left Britain and began an extensive voyage around the Mediterranean. It was this journey that inspired Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, which revolves around a typical theme and setting of the Romanticism days: a young man who is fascinated by nature and his exploration of foreign countries.

Byron eventually reached Greece in 1809. He truly loved the Balkans, having previously traveled in Albania, but Greece he liked the most. In the country known as the cradle of civilization, Byron visited many monumental, ancient sites. He also became acquainted with the Greek cause, well enough that his later contributions will forever remain in the annals of Greek history.

During this first stay in Greece, Byron also found a love interest in the daughter of the British consul and dedicated her the poem Daughter of Athens. The British poet postponed his departure as much as he could, and returned to the country again and again.

In 1812, Byron wrote yet another poem in Greece — The Course of Minerva. Unlike the previous one, this one was more politically charged. It was his way to condemn Lord Elgin, whom he despised for dismantling and administrating the shipping of almost half of the Parthenon sculptures to Britain. One half of those marbles are still in London, housed in the British Museum. The remainder is displayed in the Acropolis Museum in Athens.

Byron was already a very successful poet by then, making lots of money, most of which if he didn’t spend on travel but on women. He had some attempts to settle for a more family-orientated life, as his political career dictated, but this did not go so well.

Byron’s half-sister Augusta carried a daughter in 1814, with many speculating the child was his. The year after that, he wedded Annabella Milbanke, who gave birth to the lustful poet’s only legitimate daughter. Milbanke left Byron in 1816, after which he freely proceeded with his pleasure-seeking.

Such way of life more affected Byron’s reputation to the point he self-exiled from Britain in the spring of 1816, never coming back. That summer he spent at the Lake Geneva with Percy and Mary Shelley.

It was the so-called “Year without Summer” when heavy rain poured down all summer in Europe, flooding the continent’s biggest rivers and destroying crops. Inspired by the weather, the writers spent hours telling each other scary stories, the event eventually leading Mary Shelley to devise her infamous fantasy character — Frankenstein’s Monster.

During his stay there, Byron became involved with Claire Clairmont, Mary’s half-sister, who also resided in the house and with whom he had yet another daughter. From Switzerland Byron moved to Italy, and eventually to Greece after he was asked in 1823 to actively join the Greek struggle against the Ottomans.

At this point, Byron would invest large amounts of his own fortune to fund the maintenance of Greek warships and he even launched his own fighting unit. He first stayed on the island of Cephalonia but eventually relocated to Missolonghi, a town on the west coast of mainland Greece which heavily suffered in the war. It was here that the poet died.

In the time preceding to his death, Lord Byron collaborated with Alexandros Mavrokordatos, a prominent leader of the Greek revolutionary movement. Byron also established himself as a link between the Greek revolutionaries and the London Philhellenic Committee, a group of British philhellenes who channeled more money to support the Greek military.

Within the circle of Greek revolutionaries, things were not going so well, however. Byron would soon voice his concerns that some of the Greek leaders spent the fundraised money not for the purposes of liberation but for other political means.

Things apparently got heated between the various rebel Greek factions, since the poet wrote to a close friend in September 1823 that “the Greeks seem to be at a greater danger among them, rather than from the enemy’s attacks.”

The war concluded in 1830, effectively helping Greece to declare independence — but by that time its faithful helper, Lord Byron was long gone.

Early on in 1824, amid all the stress to keep things together, Byron succumbed to an illness. It took only a few months for the disease to extinguish all life from him. He passed away in Missolonghi, on April 19, 1824, shortly after his 36th birthday. His early death was grieved both in Greece and Britain. His remains were returned to Britain where he was laid to rest in Nottinghamshire.

Read another story from us: The Cross-Dressing French Aristocrat Who Became an Elite Royal Spy

Besides his contribution to the Greek cause, Lord Byron is also noted for expressing his support for the independence of Ireland, both in poetry and political speeches. On one occasion he also supported the independence of India, albeit his stances on these two matters were not so popular back in his day. Before fighting for Greece, Lord Byron also actively joined the liberation movement in Italy which eventually led to the birth of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861.