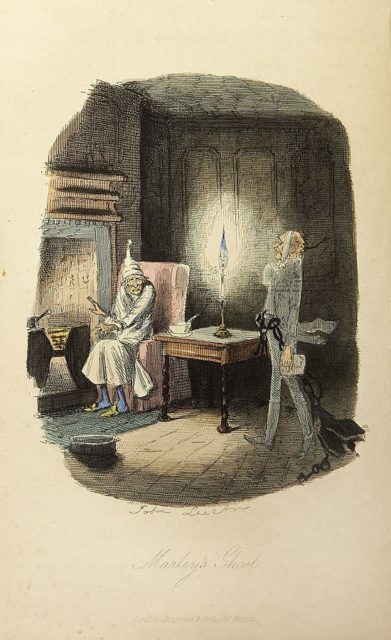

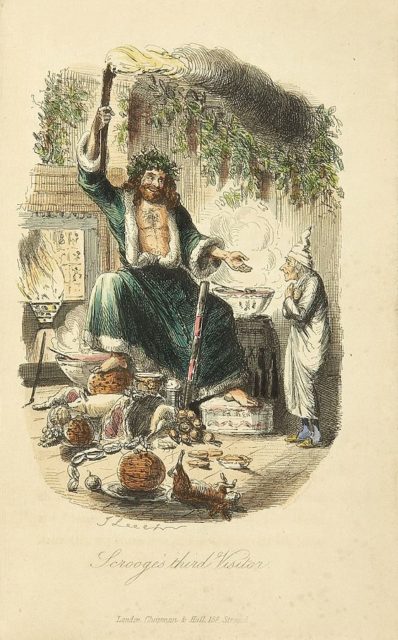

Holidays are coming and it’s time for Charles Dickens’ Christmas Carol. It is one of the most beautiful stories ever written, and Ebenezer Scrooge is still a synonym for a grumpy miser, or in modern terms, a greedy and cruel corporatist.

Ebenezer Scrooge is perhaps Dickens’ most iconic character. The puzzling part was whether he created Scrooge out of thin air, or if he was inspired by a real-life character. According to research, it’s the latter.

Legend has it that while in Edinburgh, in 1841, Dickens visited Canongate churchyard where he noticed a gravestone inscribed with “Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie – MEAN MAN”, and perhaps thought how terrible a person could have been to be remembered in such a way.

The deceased was, in fact, a “MEAL MAN” or corn merchant — Dickens’ misreading of the mans occupation inspired the name for his character: Mr. Scrooge.

In a 2014 book Inventing Scrooge: The Incredible True Story Behind Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, Carlo DeVito writes how Dickens created the protagonist of the book. Dickens was inspired by the life of John Elwes, today credited as the real-life Scrooge.

Elwes, born John Meggot, in 1714, was a Member of Parliament who was known for his miserliness.

His father, Robert Meggot, was a respected London brewer who died when John was only four, and left an inheritance of £100,000, equivalent to a couple of hundred million today. Although wealthy, John’s mother reportedly starved herself to death because she was too mean to spend money on her well-being.

John grew up to be a party-going, hedonistic, and generous man, a scholar at Westminster who liked high society and enjoyed riding and traveling abroad.

The main reason he changed his way of living and turned into a miser was his greediness for another inheritance — his uncle’s. Sir Harvey Elwes died in 1763, leaving his estate worth £250,000 (equivalent to $23 million today) to his nephew John, who even changed his name to Elwes to inherit that money.

With an eye on the fabulous fortune, John gave up his extravagant rich life to impress his uncle. But after Sir Elwes’ death, instead of enjoying the wealth, John remained unimaginably stingy.

He lived in a mansion with many rooms equipped with luxury furniture but during the winter, the young Elwes would spend most of his time in the kitchen with his servants so that he didn’t have to light another fire in the living room.

Refusing to pay money for maintenance on his house, water started dripping from every hole in the roof, and the grand furniture fell into a state of a complete decay.

He wore ragged clothes everywhere he went, and even slept in them. Sometimes he was mistaken for a beggar and given handouts, much to his joy.

His meals consisted of a single hard-boiled egg and a pancake which he kept cold in his pocket. He regularly ate moldy food, and one rumor was that he even ate a rotten moorhen he took from a rat.

The miser wore a tatty wig he found discarded in a hedge, avoided paying coaches even on rainy days, and sat in wet clothes to save the wood for the fire.

One story has it that Elwes hurt both of his legs while walking in the dark and allowed an apothecary to treat only one while wagering his fee that the untreated would heal first. He won the bet and refused to pay the doctor.

Interestingly, according to John Elwes’ friend and biographer, Edward Topham, despite being so incredibly tight with spending on himself, John’s generosity was renowned: “…his public character lives after him pure and without stain. In private life, he was chiefly an enemy to himself.”

He was elected as a Member of Parliament for Berkshire in 1772 and remained at the position for 12 years. He paid a whopping 18 pence in election expenses, and after three mandates he retired because he didn’t want to spend money on being re-elected.

Whenever he traveled to London for his job, Elwes rode a horse rather than ride in a carriage to avoid spending money on expensive turnpike tolls.

On the other hand, he was always quick to lend money and never asked for repayment, deeming asking for such things below a gentleman.

He also made a lot of investments and financed many building developments in London, some of which remain today such as Piccadilly, Portman Square, and the famous Baker Street.

As Topham wrote: “To others, he lent much; to himself, he denied everything. But in the pursuit of his property, or in the recovery of it, I have it not in my remembrance one unkind thing that ever was done by him.”

Read another story from us: Charles Dickens’ Pet Raven Inspired Edgar Allen Poe’s Most Famous Work

John Elwes immersed himself in full-time miserliness. On his death in 1789, he left £500,000 (almost £1bn today) to his two illegitimate sons.