Many centuries before caviar became a prized — and pricey — delicacy served at restaurants, something amazingly similar was eaten by Stone Age humans out of their clay pots. That’s what a new study that was published in late 2018 in the journal PLOS One has concluded.

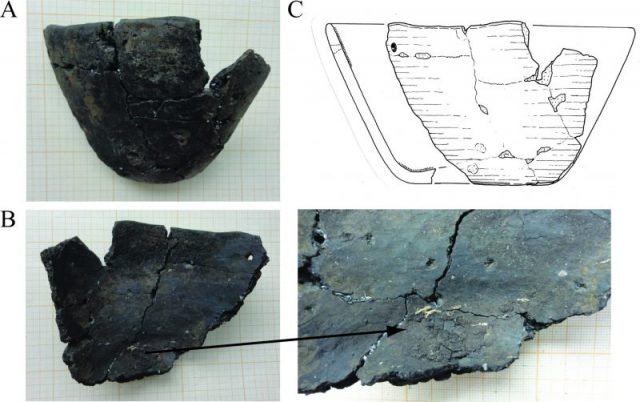

The study featured protein analysis of a 6,000-year-old cooking pot, revealing traces of cooked fish roe. The pot was recovered from an archaeological site in Germany.

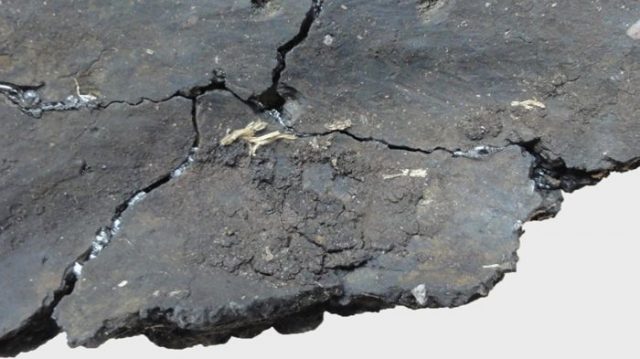

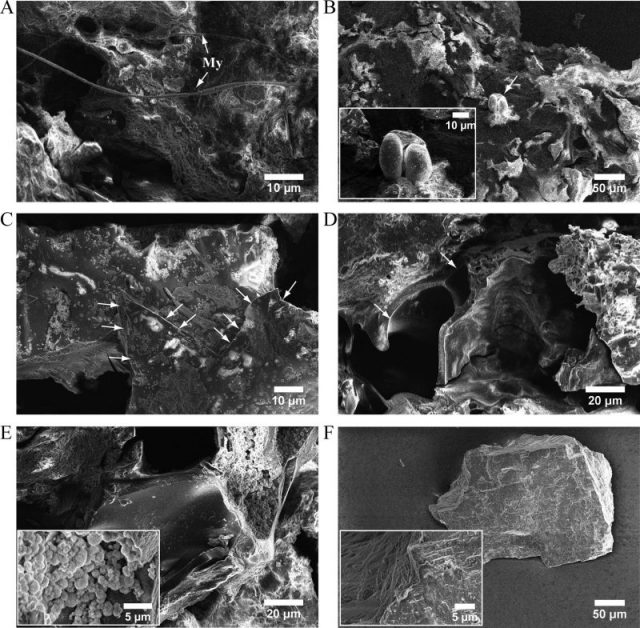

“For the study, researchers from Germany conducted a protein analysis of charred food remains caked to the shards of an Stone Age clay cooking vessel,” reported Mental Floss. “After isolating roughly 300 proteins and comparing them to that of boiled fresh fish roe and tissue, they were able to the identify the food scraps as carp roe, or eggs.”

Prehistoric societies knew how to make full use of natural resources, the study authors pointed out.

These groups of humans often lived close to rivers or lake shores. The scientists’ best guess is that these were hunter-gatherers who camped near lakes.

Trying to understand how the Stone Age people used “aquatic resources,” the scientists assembled “zooarchaeological” materials (shellfish, bones, scales), processing tools, and related art objects like zoomorphic figurines, paintings, and adornments. They also analyzed the DNA recovered from ancient fishbones.

According to Smithsonian, the lead author, Anna Shevchenko of the Max Planck Institute of Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden, Germany, “identified the elements of this prehistoric recipe by conducting protein analysis of charred food traces left on a clay cooking vessel dated to around 4000 B.C.”

Proteins on the clay that they analyzed matched those of the common carp (Cyprinus carpio).

Specifically, the proteins are common in the fish eggs. Other proteins they looked at suggest that the pot also held fish flesh. The authors say that the long-ago diners may have prepared their delicacy by poaching roe in fish broth or water, using leaves to cover the pot, according to Nature.

The clay shards that they analyzed were recovered from Friesack 4 in Brandenburg, Germany, which is a Stone Age archaeological site that has yielded about 150,000 artifacts for study, including objects made from antlers, wood, and bone, since the date it was discovered in the 1930s.

In the same study, the researchers report that they also found remnants of bone-in pork on a vessel recovered from the site.

Through such research, scientists have confirmed that some of the foods we think of as modern delicacies have been around for thousands of years, not only fish eggs but also cheese, salad dressing, and bone broth.

This research technique falls under the burgeoning field of proteomics, or the large-scale study of protein sets, according to Smithsonian. Proteomics allows researchers to focus on species- or age-specific proteins, providing a higher level of detail than most archaeological assessments of historical food substances.

The scientists said in a statement: “Burnt food particles are often found adhering to vessel shards on archaeological excavations. The analysis of their protein content helps us understand many aspects of prehistoric life.”

To analyze a ceramic bowl of burnt food leftovers found at an archaeological site in the state of Brandenburg in Germany, scientists from the Brandenburg State Office for Historic Preservation and the Archaeological Museum (BLDAM) contacted the mass spectrometry experts at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics (MPI-CBG) in Dresden.

Read another story from us: Unearthing Fast Food Joints and Takeaway Culture in Ancient Rome

“The team led by Anna Shevchenko at the MPI-CBG developed a new proteomics analysis that can identify more than 300 proteins and differentiate ancient and contemporary proteins. In this way, the researchers found in the charred remains of prehistoric food the fish roe of a carp,” according to the statement.