In recent years, machine learning has been in focus regarding issues such as transport, social networks, or virtual assistants of the likes of Siri and Alexa.

Scientists are constantly figuring out how to expand the field of use of this incredible invention, which enables computer software to progressively improve its actions by adopting knowledge gained from previous experience.

Machine learning, also referred to as artificial intelligence due to its ability to perform tasks using its own judgment, has been the subject of both praise and controversy.

However, the sophisticated algorithms that have served in providing you ads on social networks might have a grand future in philology, archaeology, and linguistics.

According to Émilie Pagé-Perron, a Ph.D. candidate in Assyriology at the University of Toronto, we might be closer than we thought to deciphering numerous Middle-Eastern cuneiform tablets written in Sumerian and Akkadian languages, all of which are several thousand years old.

Pagé-Perron is in charge of the project officially titled Machine Translation and Automated Analysis of Cuneiform Languages, which currently operates in Frankfurt, Toronto, and Los Angeles, using combined efforts to create a program capable of translating the clay tablets.

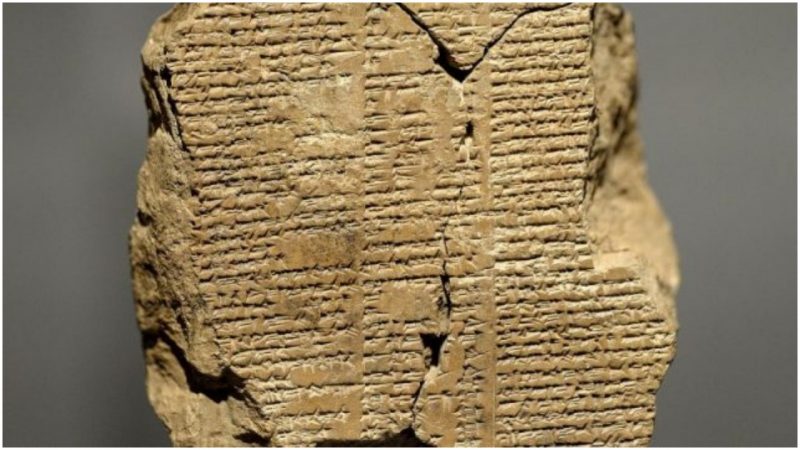

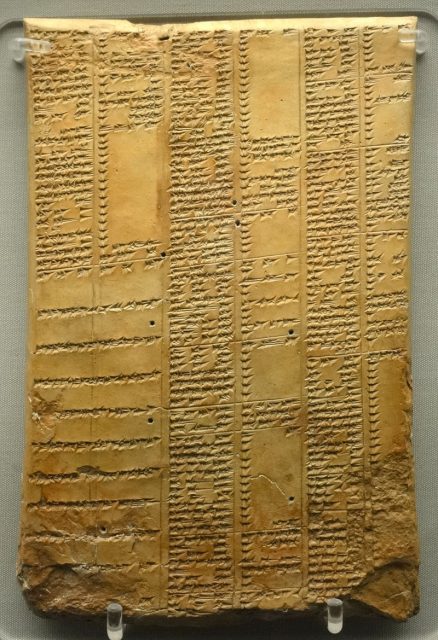

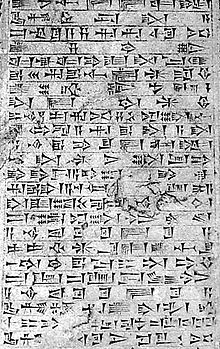

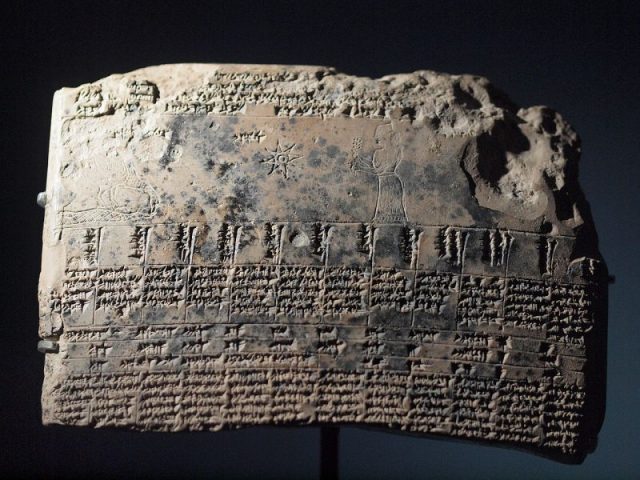

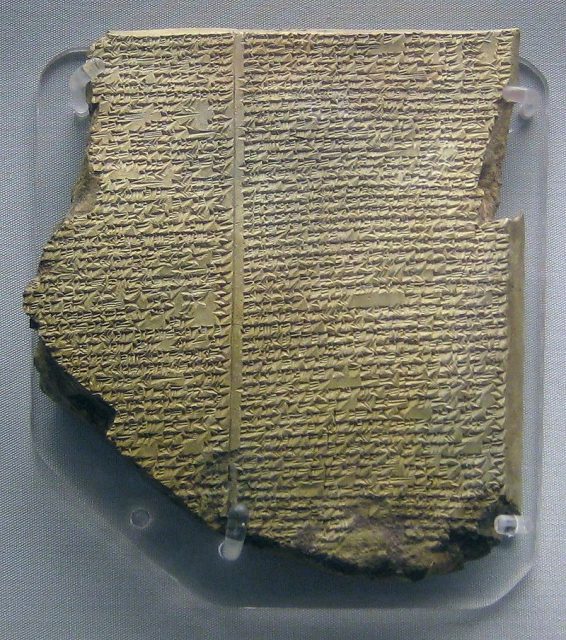

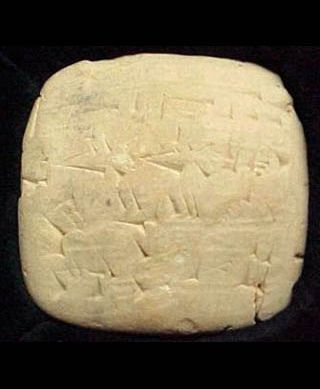

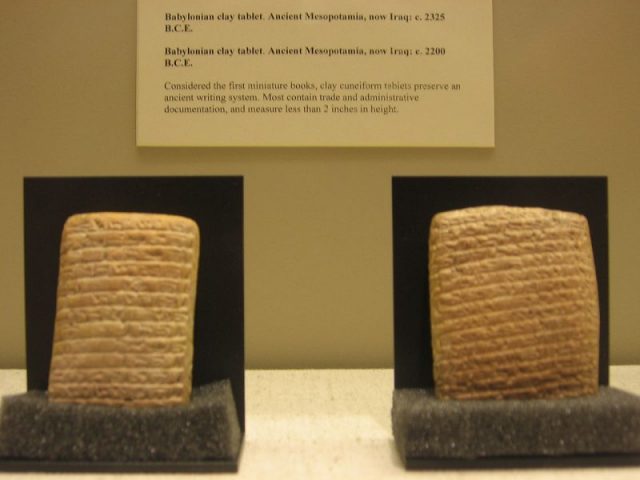

These relics of ancient languages printed in cuneiform ― literally meaning “wedge-formed” ― are among the oldest written documents known to humanity and were mostly used in Mesopotamia (today’s Iraq) more than 5,000 years ago.

While one might think that these scientists are handling a handful of texts, there are in fact more than 500,000 preserved cuneiform tablets scattered all over the world, with around 369,000 of them digitized.

Although a great number of clay tablets are available for viewing, only a limited number of them have so far been translated. The texts allude to an advanced civilization which used written language to great extent ― from administration to myths, prayers, and poetry. In fact, the Epic of Gilgamesh was first recorded using this method.

The scientists currently developing the program that would sift through the hundreds of thousands of untranslated cuneiform texts are using a sample of 67,000 administrative documents, from which they hope the software will “learn” to decipher others.

But this is no simple task. In an interview for CBC in December, Émilie Pagé-Perron described in detail the process of developing the program:

“We’re using two different methods, so we are training our algorithms on a specific set that we’ve created manually, but we’re also using methods that don’t require training. We’re using both and we’re trying to find the best methods in both camps. And at the end of the project, we hope to merge them into a pipeline that will render the best machine translation results possible.”

Handling such large chunks of data is indeed difficult, in fact so difficult that it proves impossible for scholars to do. The number of people who are familiar with these languages is very small and it would take ages to translate just a small fraction of them.

Therefore the AI is absorbing both linguistic and cultural references of the texts written in ancient Sumerian language that dates back to the 21st century BC, in order to provide a basis for future translation.

These huge portions of texts will later be used for comparative purposes as well as to produce various statistical data, which is, according to Pagé-Perron, the primary goal of the project.

While the scientists continue to craft the tools with which the cuneiform will be translated, they plan to reveal the body of texts to the public, in hopes of providing information for experts in other fields such as economics or politics.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kQsy4cM09bQ

Parallel to the research, they are also making an accessible and easy-to-handle interface that will host the data and offer it in open access under the MIT license.

Read another story from us: 4,000-yr-old Tablet is the World’s Oldest Customer Service Complaint

With the project already underway, Émilie Pagé-Perron predicts that the two teams will finish their research by June, while the whole project should be officially functional by August.