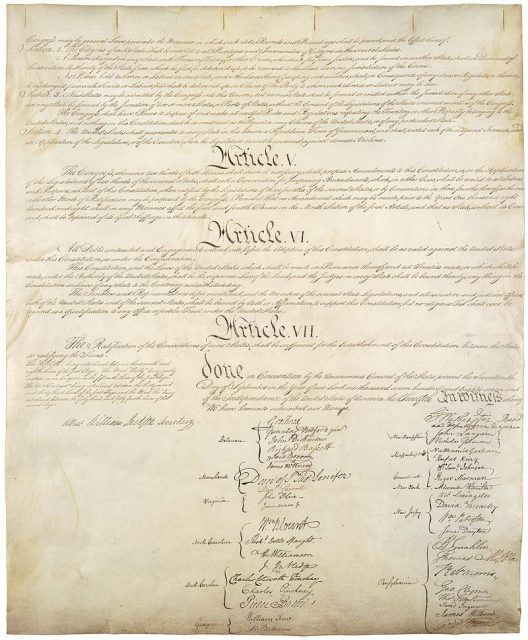

“We the people of the states of New-Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, Connecticut, New-York, New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, North-Carolina, South-Carolina, and Georgia, do ordain, declare and establish the following constitution for the government of ourselves and our posterity.”

Sound familiar? Kind of? How about this: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union…” Better, right? ‘

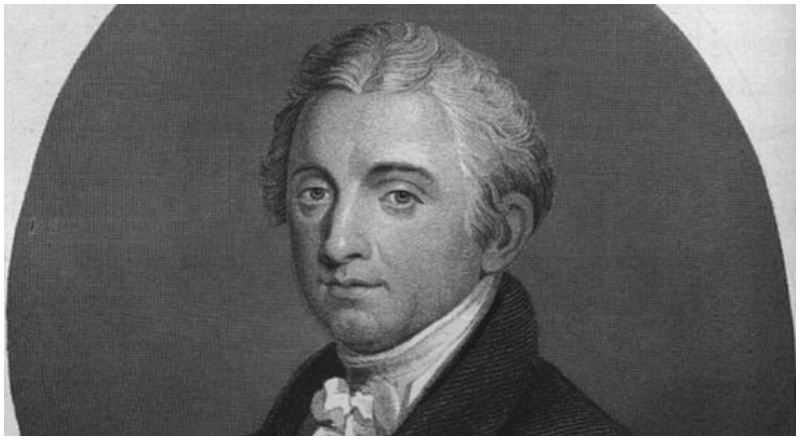

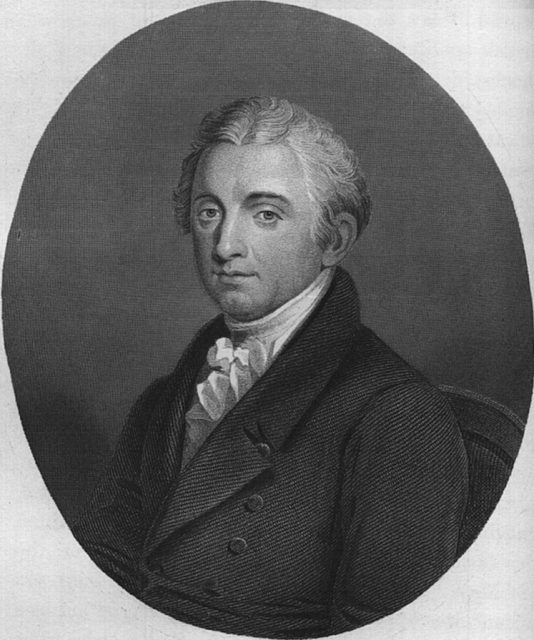

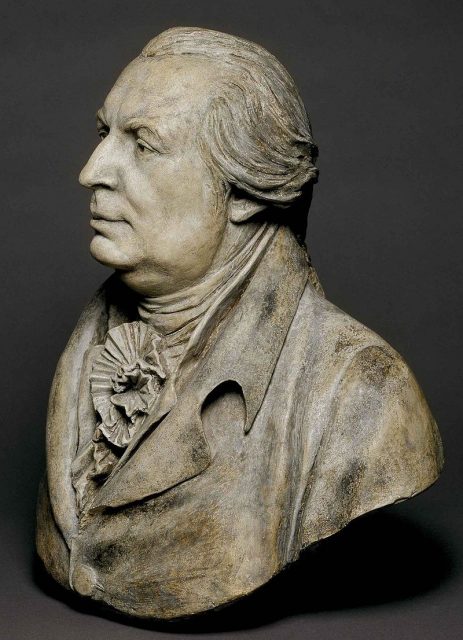

Well, you can thank a man with the unusual name of “Gouverneur” that you didn’t have to memorize that first part in school. Gouverneur Morris was one of the Founding Fathers, and today he is remembered more for his name than his life – but what a life it was.

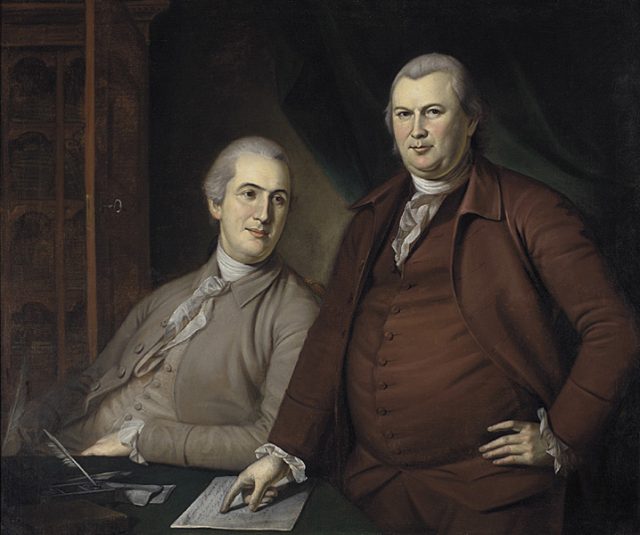

Morris was from a wealthy New York landowning family, and was in the Continental Congress during the Revolution and helped George Washington secure the funding he needed to keep the Continental Army intact.

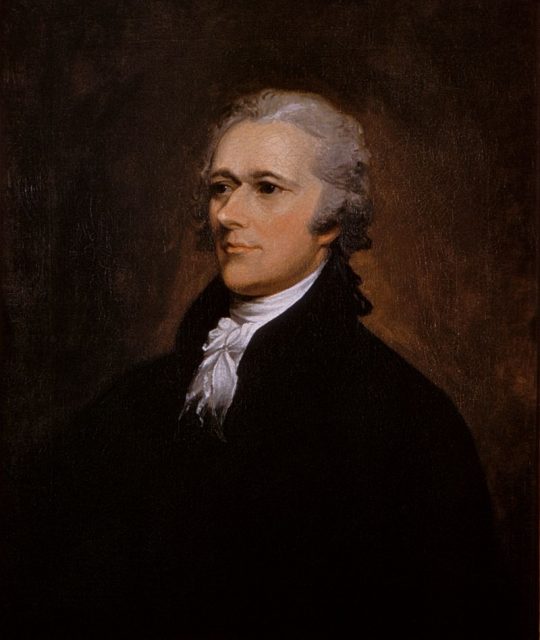

He also defended Washington at a time when members of Congress tried to remove the general from command. After time away from government, he returned to Congress in 1787 and began to promote, along with others, notably Alexander Hamilton and Washington, the idea of a strong central government rather than a confederation of states.

He was appointed to the committee which penned the Constitution and is responsible for much of its original wording.

Morris was an aristocrat who distrusted the majority of people, but at the same time, he defended the right of anyone to practice the religion of their choice, and in contrast to many of the Founders, was opposed to slavery.

In his words, “…It was a nefarious institution.”, and “It was the curse of heaven on the states where it prevailed.”

He argued against the so-called “Three-Fifths Compromise” in the Constitution, which counted black slaves as 3/5 of a person: “Upon what principle is it that the slaves shall be computed in the representation? Are they men? Then make them citizens, and let them vote. Are they property? Why, then, is no other property included?”

That was Gouverneur Morris in his professional life. His “private” life…well, it was even more radical and definitely more “out there.” You see, among Morris’ many peccadilloes was a liking for having sex in public. Yes, you read that right. A Founding Father in the late 19th and early 20th centuries who liked having sex in public places with the risk of being caught.

Morris spent time in France just before the Revolution and in the early years of revolutionary government there. In his diaries, Morris, who also liked to seduce married women, recorded occasions in which he and his married and aristocratic lover “celebrated” (that was his code-word for intercourse) in the halls of the Louvre.

At the time, the Louvre was a royal residence housing members of the aristocracy, and at times, the royal family. Morris recorded a number of episodes, including this one: “Go to the Louvre… we take the Chance of Interruption and celebrate in the Passage while Mademoiselle (the woman’s daughter) is at the Harpsichord in the Drawing Room. The husband is below. Visitors are hourly expected. The Doors are all open.”

This was all the more risky, for if he had been caught, it’s likely Morris would not have been able to get away or fight off an angry husband – his left leg was missing below the knee, and he walked with the aid of a wooden prosthesis.

He had lost the leg when a carriage hit him in Philadelphia some years earlier. The accident was a result of Morris’ trying to escape…an angry husband who was chasing him down.

That wooden leg would help him while he was in France, for during the Revolutionary period, he was riding in a carriage when a mob attempted to seize him – fancy carriages and wigs being signs of the aristocracy.

Morris apparently opened the window and waved his wooden leg about – no one is sure whether the crowd hesitated because they were shocked, or because perhaps they believed he was a war veteran, or even if Morris was trying to hit them with it – all that mattered for Morris is that he gained enough time with his leg for the carriage driver to make a getaway.

Ironically for a man who had played a role in the American Revolution to rid the Colonies of a king, Morris supported the French royal family during the French Revolution.

When Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette were being held by the Revolutionary tribunal, Morris attempted to free them, trying to raise funds to bribe their guards. As history records, this did not work. Before he left France, Morris bought Marie Antoinette’s personal furniture and returned to the United States with it as a memory of his time in France.

Even when Morris decided to get married himself, it was a bit scandalous. He married his housekeeper, who was 22 years younger than him. The age difference was not that unusual for the time, and even today, but marrying a housekeeper was.

But not only was she a housekeeper, but she had also carried on an affair with her own brother-in-law when she was 17 and had gotten pregnant by him. The baby died shortly after birth, however, and the girl was put on trial for murdering her baby.

Though she was acquitted, the stain of her affair and trial stayed with her for the rest of her life. Morris announced his marriage to her at his Christmas party. His diary records “I marry this day Anne Gary Randolph. No small surprise to my guests.”

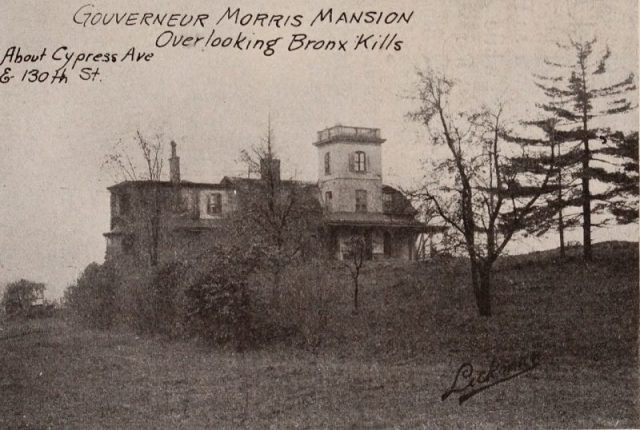

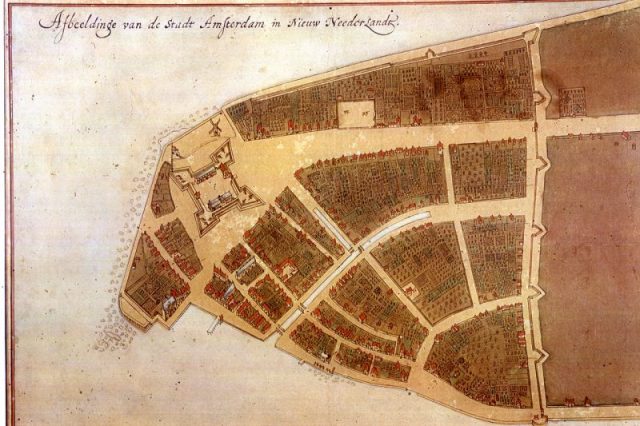

In 1811, Morris joined a committee that left a more reputable and more long-lasting legacy. He was part of a three-man committee charged with developing a growth plan for Manhattan.

Morris and his colleagues fought for (and won) a plan that involved a grid, rather than circles and grand plazas, as some in the city had argued for. Today’s Manhattan street plan is a direct result of Gouverneur Morris’ work.

At the end of his life, Morris suffered what many at the time believed to be a blockage in his urethra, making it almost impossible for him to urinate.

Today, most medical historians believe that Morris was suffering from prostate cancer, which made urination difficult.

Believing the cause to be a blockage in his pipes, Morris decided to take matters into his own hands. He used a piece of whalebone in an attempt to unclog what he thought was a blockage in his private parts.

Read another story from us: The Steamier Side of the Founding Fathers

As you can imagine, this caused a great deal of damage and the resultant infections killed him. The news of the day recorded his death as “a short but distressing illness.” To say the least.