Time can be a complete menace to works of art. Dust, mold, mildew, dirt and even the varnish originally used on a painting can become thick and dark over the years, eventually obscuring or even completely hiding from view the original work.

Art conservation is a highly skilled and painstaking trade, in which the layers of grime are removed one time section at a time until the original piece is restored to its former glory.

However, despite what may have originally been good intentions, not all art conservation is successful, or even done professionally. In other cases, works of art are destroyed deliberately, as a political statement or act of violence. Here are just a few examples of works of art ruined by human intervention.

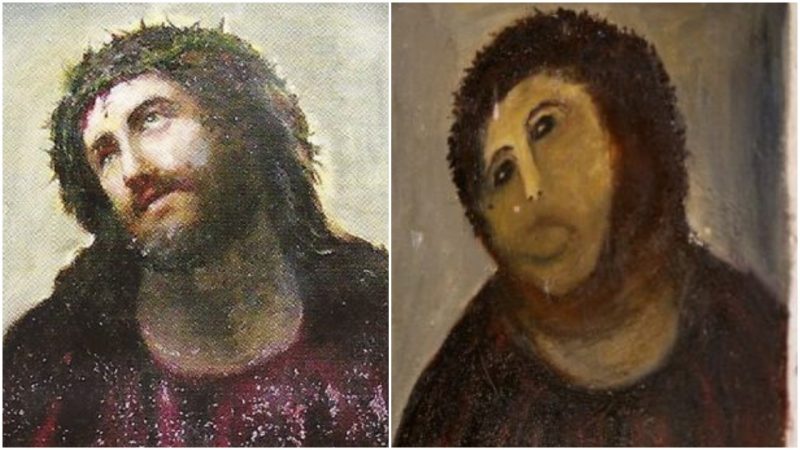

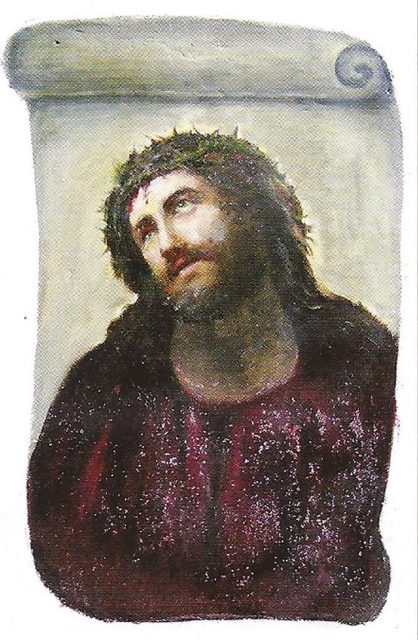

Ecce Homo by Elias Garcia Martinez

Originally painted in 1930, this fresco of Jesus adorns the walls in the Sanctuary of Mercy church in Borja, Spain. An attempt was made in 2012 to restore the fresco by Cecilia Giménez, a senior untrained in art conservation.

Unfortunately, it did not go well. Her restoration effort has been compared to a monkey, and the painting is now sometimes known as Ecce Mono, or Behold the Monkey.

Thanks to social media, news of the botched restoration spread quickly, and the priest of the church, Father Florencio Garces, believed that the fresco should be covered up.

However, the image has now become a tourist draw; in 2013, it brought around 40,000 visitors to the church and generated more than €50,000 for a local charity. There is now an interpretation centre on site, as it continues to draw visitors from around the world.

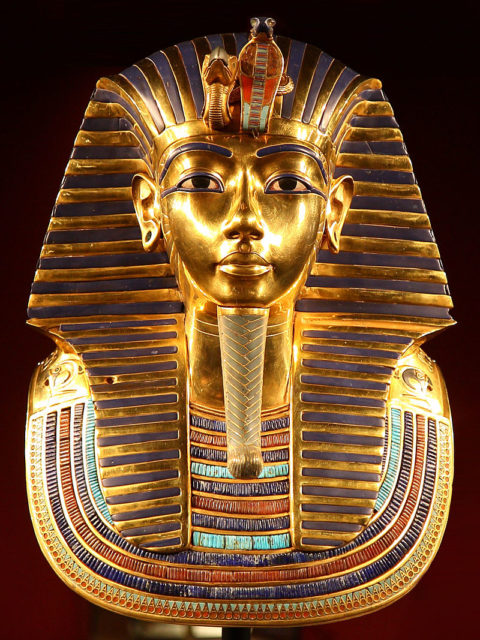

King Tut’s beard

The golden burial mask of King Tutankhamen is arguably one of the most well-known pieces of art in the world. However, the beard of the mask was accidentally broken off in 2014, and workers tried to reattach it using epoxy, which in turn caused extensive damage to the priceless artifact.

A team from Germany and Egypt began a professional restoration of the mask in October 2015, with the aim to not only reattach the beard properly but also conduct a complete study of the mask, which had not been done before. The restoration took nine weeks and the beard was successfully reattached using simple beeswax, which would have been a common material in ancient Egypt and is less likely to cause damage to the metal on the mask.

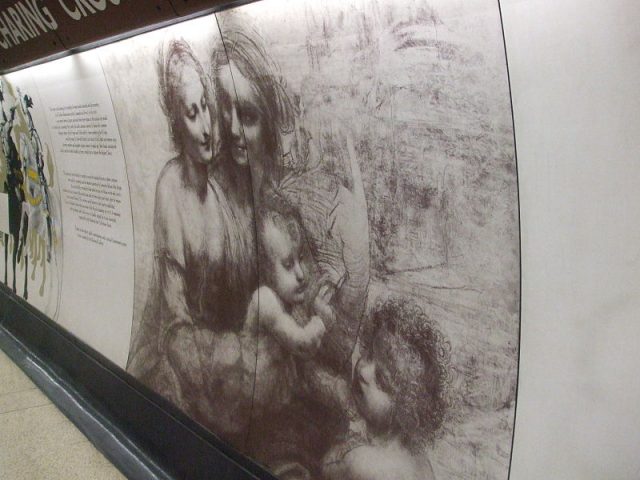

The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist, by Leonardo da Vinci

In 1987, a man by the name of Robert Cambridge walked into the National Gallery in London, England, with a sawn-off shotgun and fired directly at a work by Leonardo da Vinci, called The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist.

Mentally ill, Cambridge wanted to bring attention to the “political, social and economic conditions of Britain” with his actions. The shot shattered the glass covering the painting and caused significant damage to the work.

Fortunately, the shotgun pellets did not completely penetrate the laminated glass protecting the work, although a hole about 6” in diameter was torn in the Virgin’s robe. The multiple tiny fragments of paper that were left were painstakingly glued back together using surgical instruments and a magnifying glass. The restoration took several months. In the end, only about 1 square centimeter of the work was lost.

Fountain by Marcel Duchamp

A porcelain urinal, this sculpture was produced by Marcel Duchamp in 1917, and a replica is housed at the Tate Gallery in London, England (the original was lost in 1917).

Being a urinal, the piece has been the subject of much controversy of the years, and in 1993 an artist named Kendell Geers urinated in a replica of the work at a show in Venice, Italy.

Musician Brian Eno also relieved himself in the Fountain replica while it was on exhibit at the MOMA that same year, as did another artist, Björn Kjelltoft, in Stockholm in 1999.

Significant damage was done, however, in 2006 when performance artist Pierre Pinoncelli attacked the porcelain work with a hammer. It has since been restored.

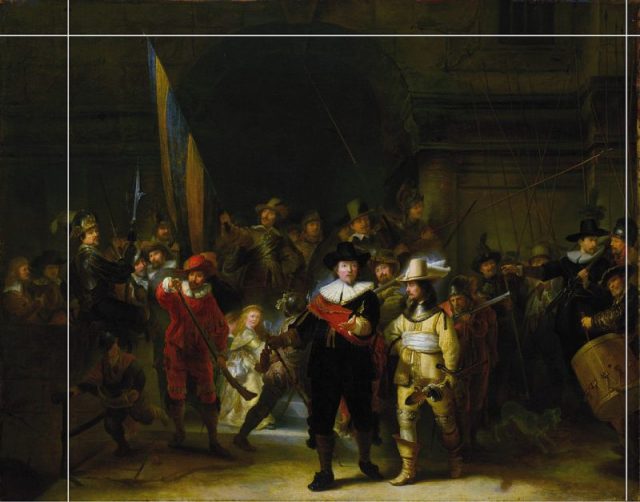

The Night Watch by Rembrandt van Rijn

One of the best-known paintings in the collection of Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, The Night Watch has been attacked three times in its lifetime. In 1911, a shoemaker protesting his failure to find work slashed it with a knife.

Then in 1975 it was slashed again, this time by a teacher, Wilhelmus de Rijk, who believed he was ordered to do it by God. The restoration of the large knife marks took four years, and evidence of the damage can still be seen on the painting.

In 1990, the work of art was sprayed with sulphuric acid by an escaped psychiatric patient. Fortunately the acid only penetrated the varnish and the work was fully restored. The painting is expected to undergo a full restoration beginning in July 2019, while remaining on public view.

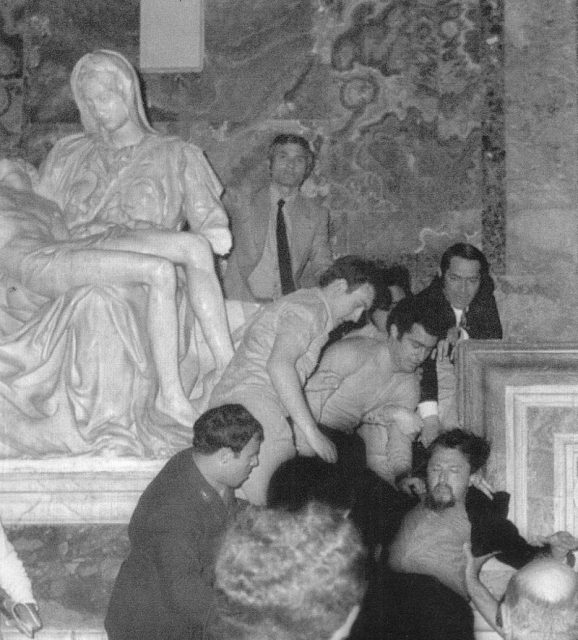

Pieta by Michelangelo

Housed in St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, Michelangelo’s Pieta was made for Cardinal Jean de Bilhères’ funeral monument, but was moved to the basilica in the 18th century. Interestingly, it is the only piece that Michelangelo ever signed.

In 1972, a man named Laszlo Toth attacked the priceless sculpture with a geologist’s hammer, all the while shouting “I am Jesus Christ; I have risen from the dead!” As a result of his efforts, Mary’s arm was detached at the elbow, a chunk of her nose taken off and part of her eyelid.

Over 100 marble fragments flew off the sculpture, some of which were picked up by visitors to the Vatican, including Mary’s nose, which eventually had to be reconstructed from a block cut from the back of the piece.

The repair of the statue was one of the most delicate and controversial art restorations in history. Some wanted the statue to remain damaged, as a sign of violent times; others believed it should be restored to its original state, but with a clear indication of what was original and what was new.

In the end, the Vatican decided that the Pieta would be restored such that no traces of intervention would be visible.

Antonio Paolucci, director of the Vatican Museums, said that “with any other statue, leaving the wounds [of the attack] visible, however painful, could have been tolerated. But not with the Pieta, not this miracle of art.”

10 months after the attack, the Pieta was back on display — although protected by bulletproof glass.

Statue of St. George, Spain

Similarly to the Ecce Homo incident, an amateur attempted to restore a 16th century wooden sculpture of St. George in the Church of San Miguel de Estella in Navarre, Spain.

Rather than contracting a professional conservator, a local art teacher was hired to conduct the restoration. While her intentions may have been noble, the statue has since been compared to a Disney character, with its new bright pink face, and red and grey suit of armour.

Instead of cleaning the original polychrome paint, the teacher, known only as Carmen in the local media, simply painted over it. According to the town’s mayor, Koldo Leoz, the restoration was conducted without consultation and is “unfortunate” in its results.

Taking it further, the Spanish Conservationists and Restorers Association (ACRE) contacted prosecutors to explore whether or not the failed restoration would constitute “a crime for damage against objects of cultural and historical value.” Ironically, prior to the restoration, the statue had been in rather good condition considering its age.