The daguerreotype was the process of development of photography which entered use in 1839 and quickly gained massive popularity in Europe. Invented by a French photographer, Louis Daguerre, it reigned supreme as the first-ever photographic process available to the public. The process was affordable and relatively easy to produce, launching photography from its experimental phase right into the homes of common people and curious amateurs.

Naturally, during this time the photographic portrait also gained popularity, threatening to replace portrait painting completely. The invention left Europe, and pretty soon found its way into North America, where daguerreotype photography was pioneered by a man called Matthew Brady, who witnessed the birth of the technique first-hand in France.

By 1844, Brady had opened the first photography studio in New York, where he battled through prejudice and fear in order to establish himself as the master of photography in the American metropolis. Later on, he would become the official photographer of the likes of Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, and Abraham Lincoln, as well as the man who pioneered war journalism, with his images of the Civil War.

Around this time a great number of portraits were made, mostly involving younger people who were following the European trend and were keen on discovering more about this emerging trade and the science behind it.

However, for a generation of New Yorkers born in the 18th century, the recent invention wasn’t something they were going to adapt to easily.

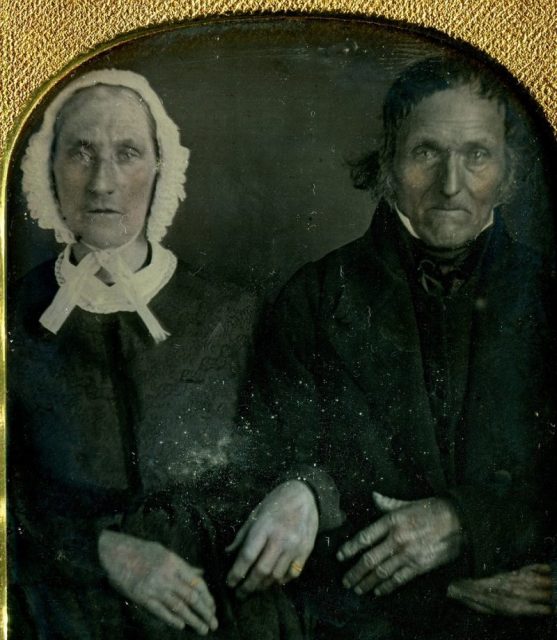

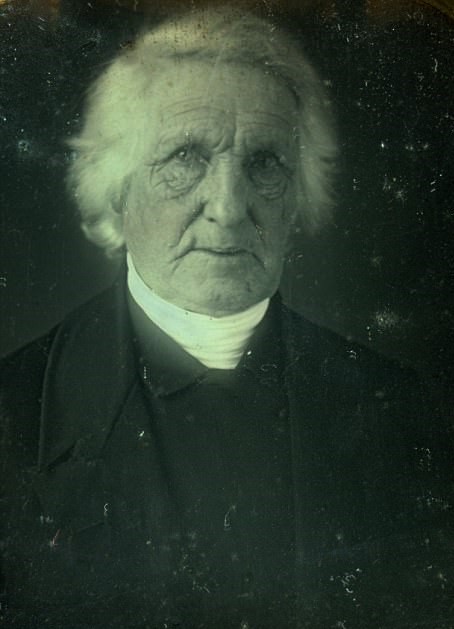

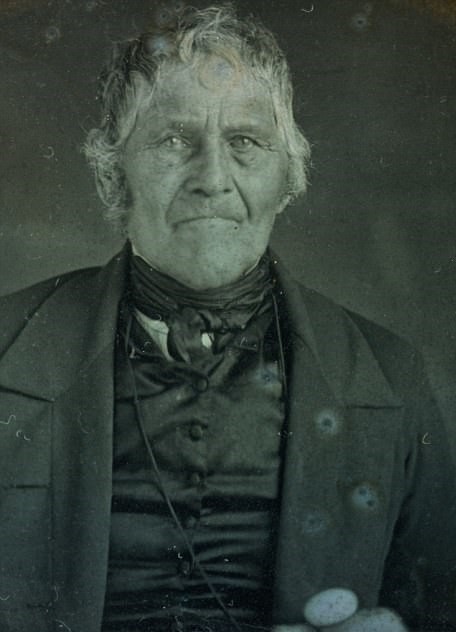

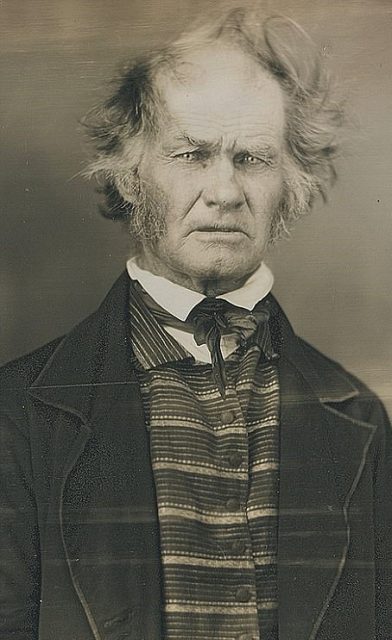

On the other hand, some older people, most of whom were distinguished professionals and other dignitaries, agreed to pose as models in the early 1840s. Most of the models were couples who agreed to immortalize their presence in the world, as well as the lasting bond that they had with their partners.

Thanks to this endeavour they became the oldest generation of people ever to be photographed since most of them were born in the 1700s, with some of the men even being veterans of the American Revolutionary War.

The women are mostly wearing typical bonnet headgear, while the men are dressed in their formal attire. What they share, however, is the reluctant gaze, as their faces clearly reflect a feeling of mystery and confusion.

It is only presumed that a number of these photos were Matthew Brady’s work, for he was the most active photographer of the era, residing in New York, but a number of other artists might have participated in making this unique and historically priceless photoshoot.