It is 1917, the height of the first World War, and the people of Paris are plagued with bombing attacks by German Gotha Bombers and Zeppelins.

This tactic is meant to dishearten and demoralize the French people, to drain them of their resolve. But instead, it has the opposite effect. The people of Paris gather in the streets, shouting and taunting the Germans that fly overhead.

But a secret meeting is being held to create a buffer between the French people and the raids that become more frequent by the day.

The Daily Beast reports that an Italian engineer named Fernand Jacopozzi came up with a plan that could avoid further destruction.

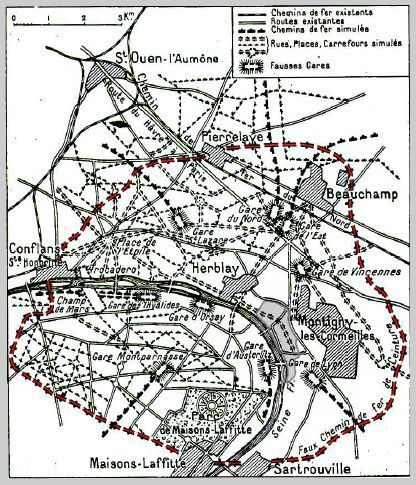

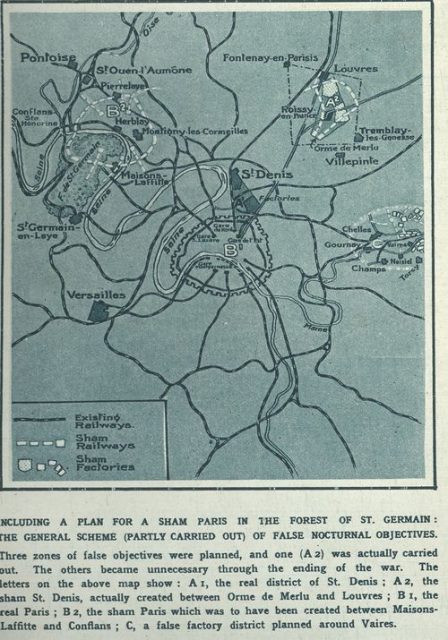

He proposed that replicas be made of major parts of the city, ranging from industrial zones and train hubs, to the city center with iconic landmarks such as the Arc de Triomphe, according to The Telegraph.

Plans were at once detailed and thrown together, relying on the fact that aviation at the time was dependent on visual flight and target acquisition, without advanced equipment like radar to confirm where the targets were, meaning that the replicas only had to be convincing from the air.

Three areas were planned for the creation of the replica buildings. To the northeast, a major train hub. To the northwest, a copy of the city center.

To the east, an industrial zone with fake lights and smoke. And connecting all of these fake neighborhoods would be a rail line with a train made out of wood.

But there was a problem, writes Military Factory. Paris, the City of Lights, shone brightly even into the early morning hours. That’s what made it such an inviting target to the German bombers, as they could fly by night and bomb the city, allowing them to evade the increasingly effective anti-air tactics of the French against their wings of tightly knit bombers and the gargantuan zeppelins.

Jacopozzi provided an ingenious solution to convince the Germans the faux Paris is real. Culture Trip relates that the engineer proposed using an intricate pattern of multi-colored lights to replicate large swaths of the city, making it look like Paris had tried to initiate a blackout, but failed. Meanwhile the real Paris actually would enforce a strict blackout, becoming practically invisible to the eyes above them.

He even created a system to place aboard the fake train, testing it, according to Paris Invisible, from a viewing platform on the Eiffel Tower to see if it looked convincing.

The government approved this plan, sending resources out and hiring the craftsmen necessary to raise the structures. The streets were laid out with tremendous attention to detail, copying sections of Paris exactly.

A transparent paint was even applied to the tops of the fake industrial buildings to simulate the look of glass that would ordinarily be there. Yet all of this work would be for naught.

The final German air raids were in September of 1918, a month before the end of the war.

As the end of the war loomed, and the city of Paris was safe from the air raids, Invisible Paris reports that only a few industrial buildings and one fake train station had been built, and had never seen use in the war.

As the Armistice passed, city officials moved to quickly disassemble the structures, not wanting to tip off the Germans to their subterfuge.

This was not the end for Fernand Jacopozzi however. He would go on to work on the lighting projects for the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe, making a name for himself during the Roaring Twenties.