Teeth reveal all manner of things about our health, and it’s no surprise that archaeologists often rely on evidence from teeth and bones in order to draw conclusions about the lives of our ancestors.

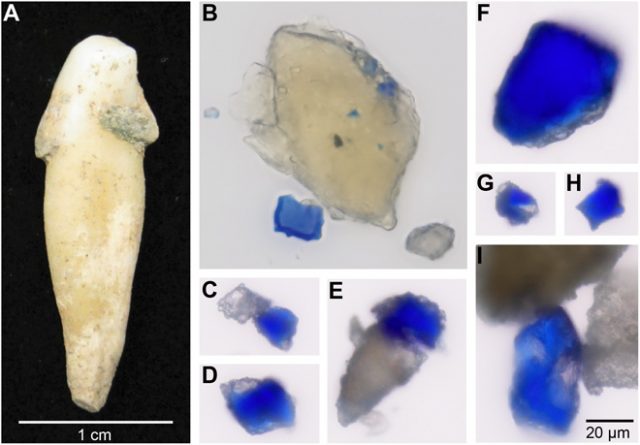

However, the discovery of a blue-stained tooth in the corpse of a medieval nun has left historians particularly excited about the possible implications.

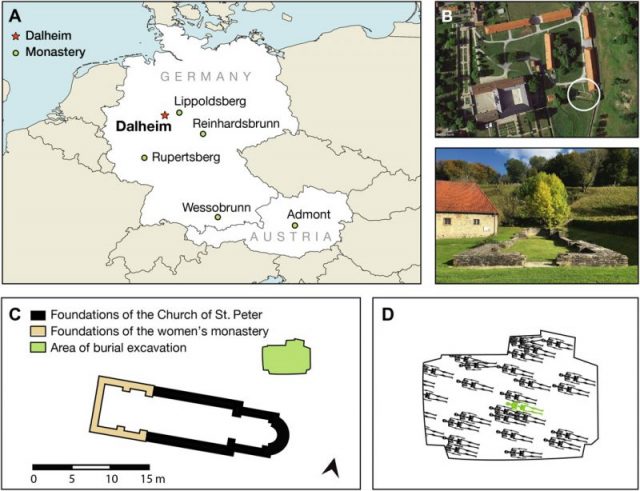

An interdisciplinary team of archaeologists, anthropologists, historians and scientists recently published a groundbreaking study in which they report that bright blue deposits were found in the teeth of a medieval nun at a monastery in Dalheim, Germany.

According to the report, published in the journal Science Advances, this particular woman had an astonishing number of ultramarine flecks in her mouth, which appeared to have accumulated over many years.

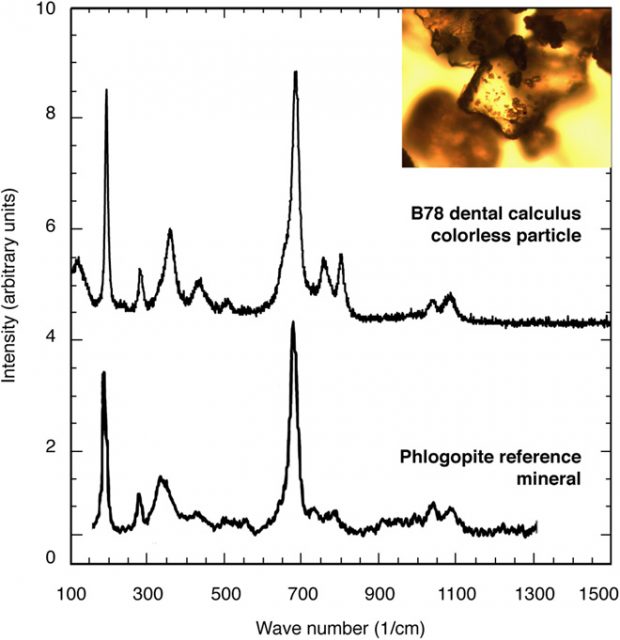

Further analysis revealed that the blue flecks were actually lapis lazuli, a rare and vibrant blue pigment found only in an area of Afghanistan.

This rare and expensive material was used in the production of lavishly decorated manuscripts, and was reserved for only the most important texts.

Blue is a notoriously difficult color to manufacture, and the brilliant, bright hue created by lapis lazuli was in high demand for exceptional works of art.

Lapis lazuli was imported from Afghanistan, ground into a powder and mixed with water to make a pigment, which was then carefully applied to illustrated manuscripts by trained scribes.

Only the most accomplished and experienced scribes would be trusted to handle such a rare substance; it was at least as expensive as gold and much more difficult to find.

According to the report in Science Advances, the team found that the teeth contained many flecks of lapis lazuli that had become embedded in the dental calculus, hardened plaque that gathers on the teeth over the course of a lifetime.

Furthermore, the pattern of these deposits was consistent with a licking motion, as if they had accumulated when the scribe licked the end of her brush with her tongue.

Analysis of the corpse indicated that this particular scribe was female, and aged between 45 and 60 years old when she died. Aside from the extraordinary amount of lapis lazuli they found in her mouth, the team agreed that she was an otherwise normal and healthy woman.

Radiocarbon dating techniques revealed that she was alive sometime between 997 and 1162, during a period in which European monasteries were flourishing.

Monasteries were a hotbed of artistic activity in medieval Europe, and all kinds of religious, liturgical and historical texts were produced in these institutions.

Manuscript illustration is one of the most elaborate and beautiful forms of medieval art, and these objects represent labors of love created by skilled scribes trained in the religious community.

It has often been assumed that the majority of scribes who produced these beautiful works of art would have been men. Some historians have even gone so far as to suggest that women would have been prohibited from illustrating important manuscripts in this period.

More recently, however, important work by historians such as Alison Beach has shown that female scribes were much more prevalent in European monasteries than has previously been assumed.

Part of the difficulty in identifying female scribes is due to the fact that the majority of medieval texts were produced anonymously, and even those that were signed rarely include a female name.

As a result, this discovery marks an important breakthrough. It provides concrete evidence that women were involved in the production of some of the most important manuscripts produced in religious foundations, as lapis lazuli would have been reserved for only the most special texts.

It also may point to the significance of the monastery at Dalheim as a center of manuscript production. Prior to this research, very little was known about the monastery and what went on within its walls.

The study is also important in showing the movement of exotic goods on long distance trade routes from Asia, and the ways in which they were used in Western European societies.

This supplements recent research that attests to the connections that existed between Europe, the Middle East and Central Asia in the medieval period, and emphasizes the vitality of medieval trading routes.

Read another story from us: Incredible Forest ‘Crop Circles’ Appear in Japan

The members of the team are particularly hopeful about the possibility of applying the techniques developed in this study to other contexts. Who knows what else could be revealed by analyzing medieval teeth?