The 1790s were a hard time for the British Empire. The United States had recently taken their place as a new, sovereign country. England had been at war with the French and Spanish all over the world, but especially in the West Indies and The New World. To top it all off, sailors in the Royal Navy had become disillusioned and disheartened under the tight reins of British Officers.

They were frustrated by the conditions in which they lived and in the pay which hadn’t gone up in almost a full century — the kind of situation that would push anyone to their limits. For Britain, these problems came to a head in 1797.

In April of 1797 the fleet, anchored at Spithead near Portsmouth, came together and mutinied in response to the incredibly harsh treatment that they’d suffered under the British flag.

Sailors demanded better pay and more bearable working conditions. After a short deliberation, the men who took part in the mutiny were given their demands and pardoned.

This would be the first of three major mutinies, the second coming in May 1797 at Nore anchorage on the Thames. The first ship to mutiny was the Sandwich, but they were joined by other ships.

Turbulent London reports that the sailors first demands were similar to the Spithead fleet demands: better pay and better working conditions. If they had stopped there, perhaps they would have been more successful.

They also, however, made demands including the dissolution of Parliament and immediate peace with France. The mutineers were offered the same concessions given to the Spithead fleet; however, radical elements of the crews continued to demand more.

Possibly their worst mistake was to blockade the Thames. Their hope was to prevent ships from entering London which, if successful, could cripple the economy.

The government simply denied food to the mutineers. That, plus internal dissent, led to ships departing the blockade and the mutiny eventually dissolved. Leaders of the mutiny, approximately 29 men, faced swift punishment including hanging, flogging, or being sent to Australian penal colonies.

Sadly this wouldn’t be the last or worst mutiny to happen in 1797. The HMS Hermione was a 32 gun frigate flying British colors under the command of Captain Hugh Pigot, son of Admiral Hugh Pigot.

At the age of 24, Pigot was given command, primarily because of the influence of his father according to Find a Grave. His first command was on the HMS Success, where his abuses were documented by the crew. In his short tenure, he had 85 members of the crew flogged, two of whom succumbed from their injuries. This comportment would continue to his command on the HMS Hermione.

On September 20, 1797, the Hermione was hit by a sudden squall. Captain Pigot called for the topsails to be reefed, with the threat that the last man down would be flogged. While trying to move as quickly as possible to avoid the punishment, three teenage members of the crew fell from the rigging high above the ship and died on the deck. As it turned out, this would be the final straw.

Two days went by, with the crew growing more restless and eventually furious with how they were treated and the officers who visited cruelty upon them. On the 22nd of September, after probably too much rum, the explosive situation finally went off. The crew stormed the deck, armed with cutlasses, tomahawks, and bayonets.

The men attacked Pigot in his bed. He yelled for help, but for Pigot, no help was coming. He was tossed overboard, mortally wounded but still alive, along with nine men that were loyal to him.

The crew then took the ship to La Guira in Venezuela and gave it over to the Spanish. Spain accepted the ship, and many of the crew served on Spanish and French ships.

Some men fled, attempting to outrun the law. Of the 62 men involved in the mutiny, 33 of them were captured and 24 were executed for their crimes.

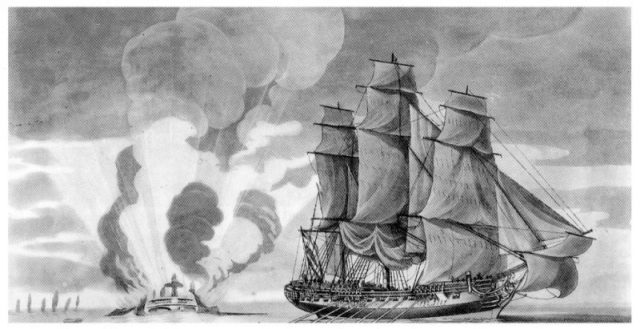

The Hermione would later be recaptured from the Spaniards by Captain Edward Hamilton in the HMS Surprise. According to Nicholas Pocock’s article on the Royal Museums Greenwich website, Hamilton had hoped to sneak in and recapture the heavily armed ship.

They were seen, however, and the crew of the Hermione (renamed Santa Cecilia) were prepared. Still, after a heated battle, Hamilton’s men boarded the ship and recaptured her.

Hermione was taken back to Great Britain, renamed as HMS Retribution, and served the navy for three years before being decommissioned, then scrapped in 1805.