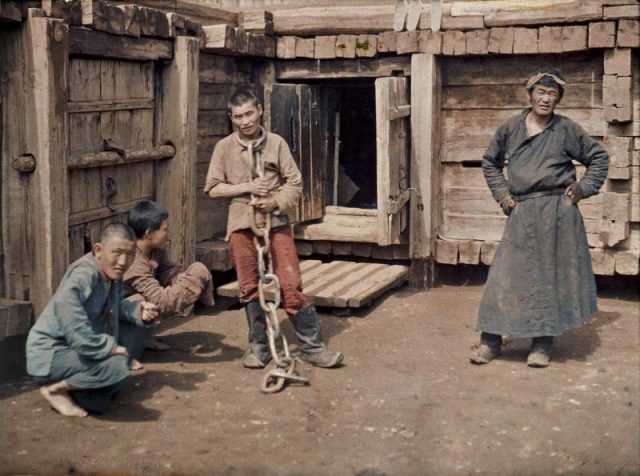

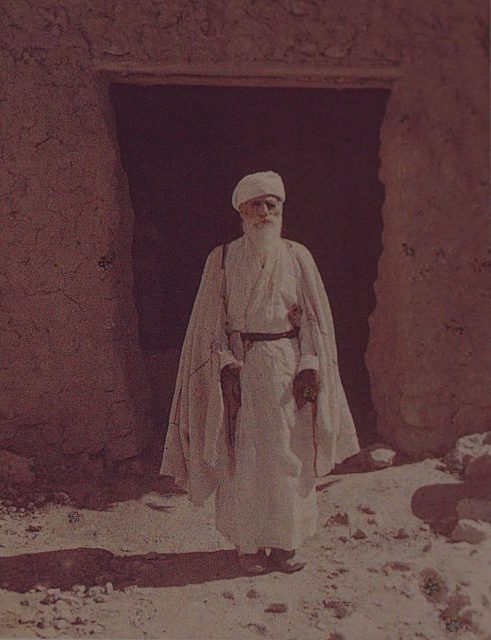

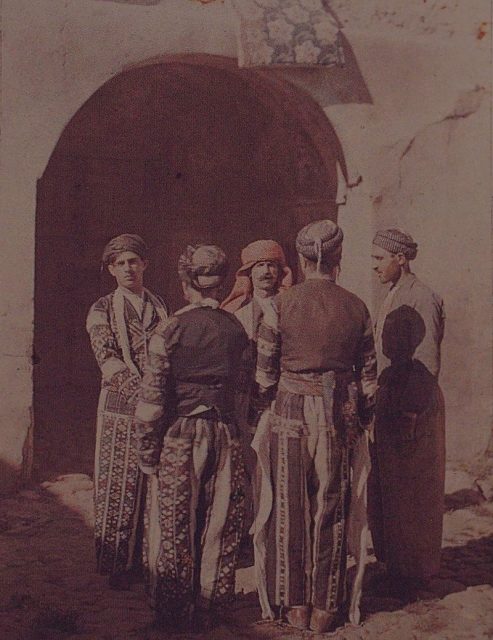

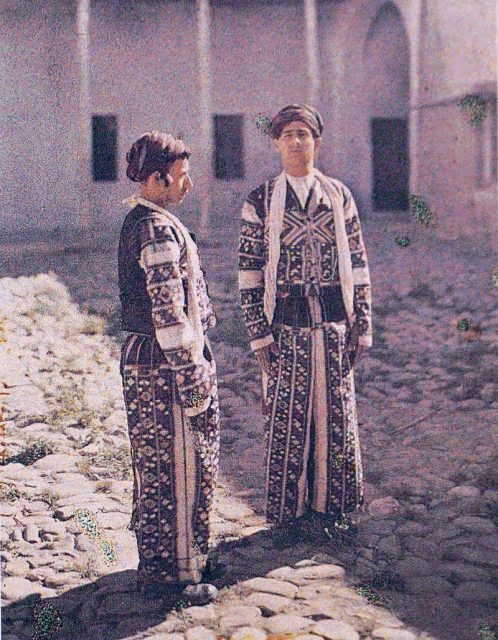

It might come as a surprise, but it wasn’t long after photography became widespread that experiments with color took place, creating vivid images which suggested endless possibilities.

As early as 1855, a Scottish scientist called James Clerk Maxwell made notes on how it would be possible to add color to black and white photographs.

In 1861, Thomas Sutton followed his instructions and managed to produce a three-color image of a Scottish tartan ribbon. However, this was simply a method of coloring black and white photographs. Although the results were similar, inventors and enthusiasts alike were looking for a solution that would create photographs in color without additional colorization.

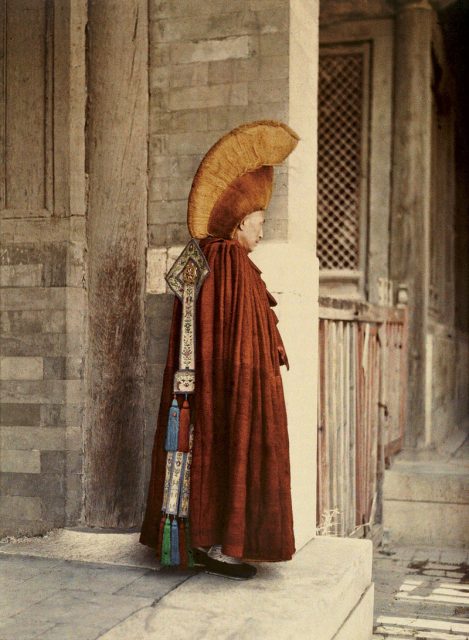

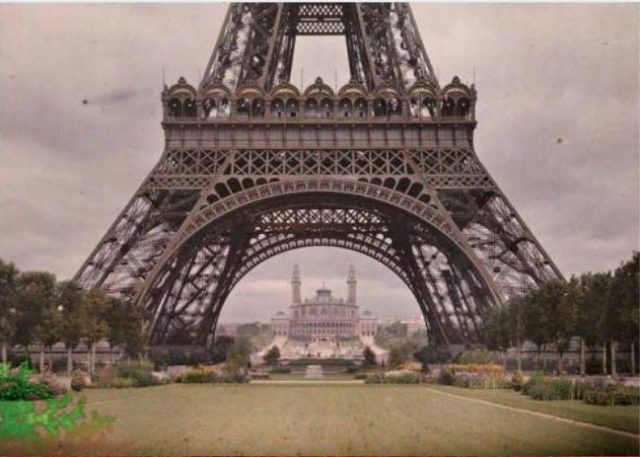

This didn’t happen until 1903, when the Lumiere brothers ― the same ones responsible for the invention of the cinematograph ― patented a process that would change everything. The Lumiere Autochrome entered commercial use in 1907, and quickly became the dominant process of color photography in Europe.

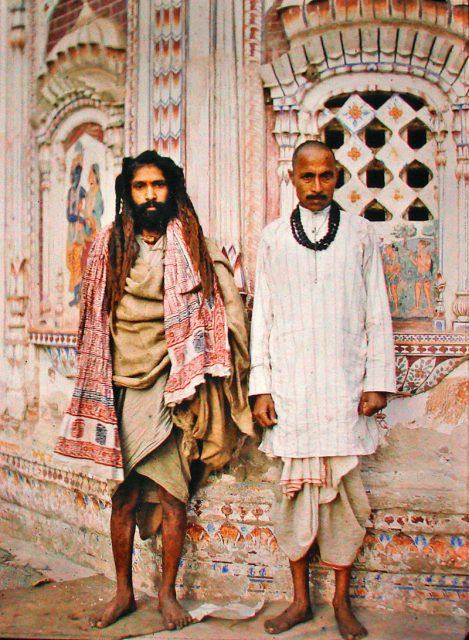

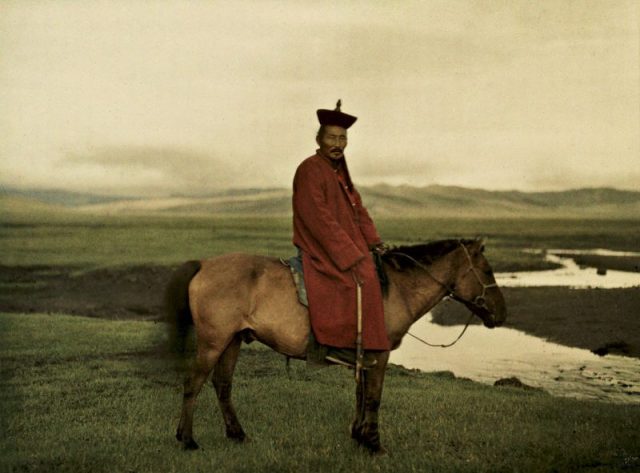

The Autochrome relied on earlier research conducted by Louis Ducos du Hauron and established a method that utilized dyed grains of potato starch in red-orange, green, and blue-violet which acted as color filters. Together with a light-sensitive emulsion, the Lumiere Brothers were able to imprint colors, creating a never-before-seen effect.

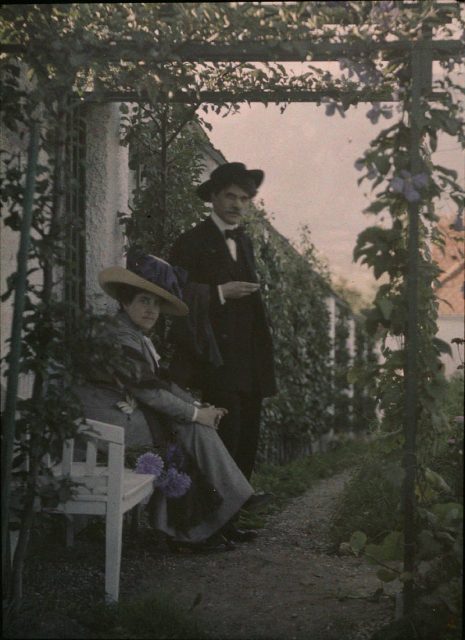

Their vivid photographs quickly captivated rivals and supporters alike ― it simply surpassed any other attempt of color photography, and certainly surpassed colorization methods, as they instantly became outdated.

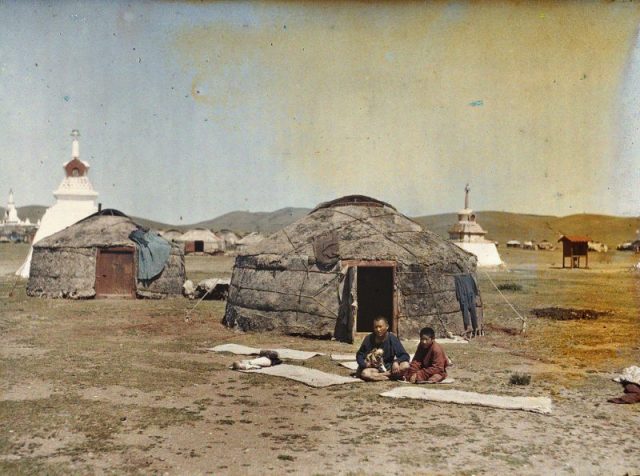

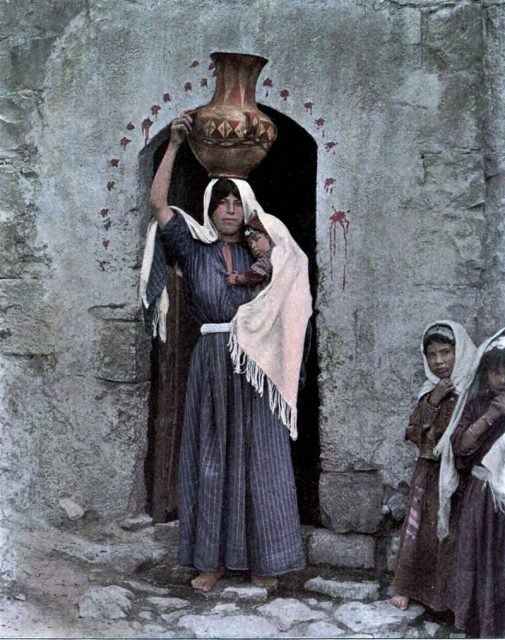

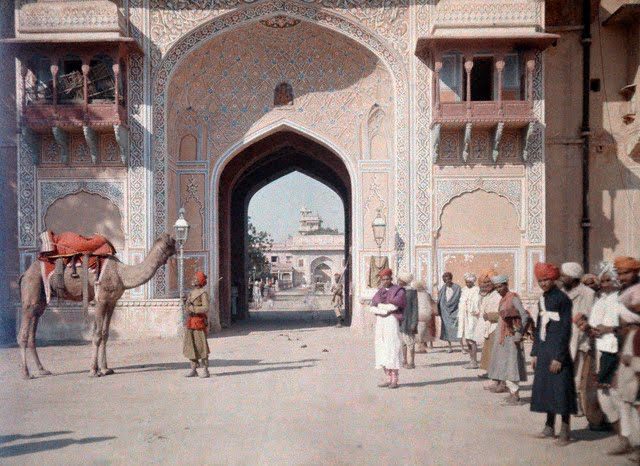

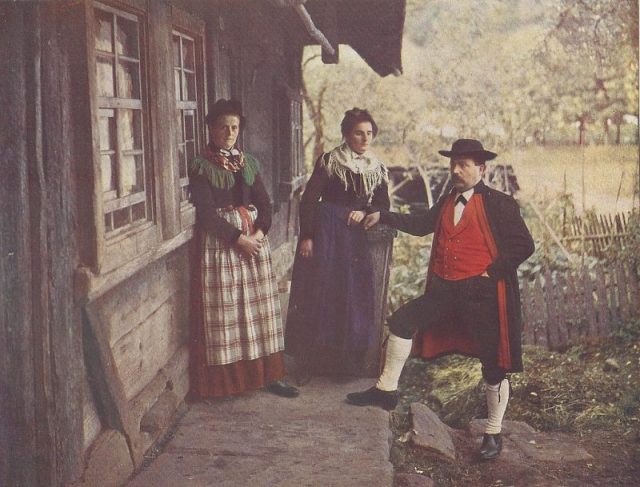

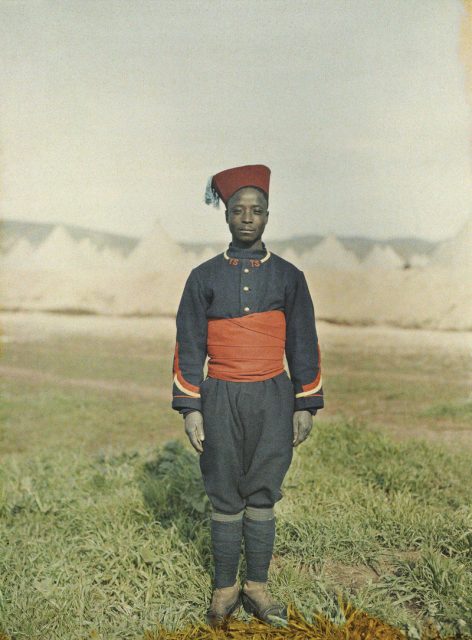

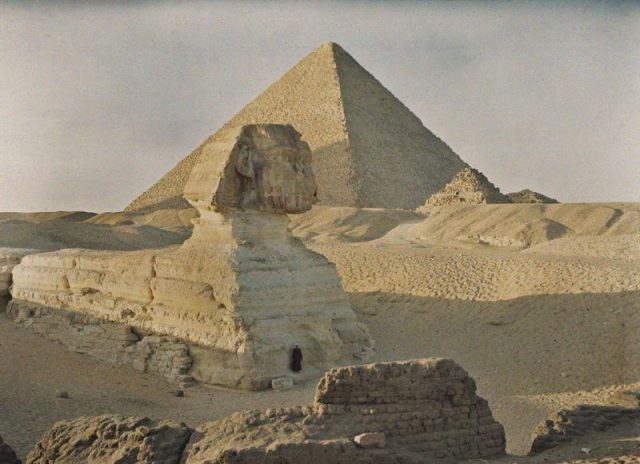

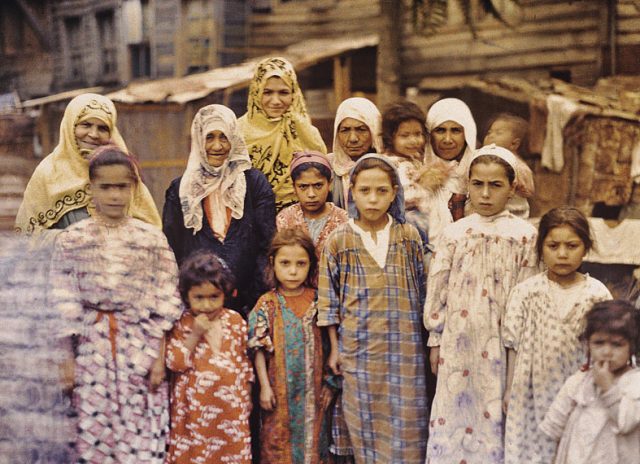

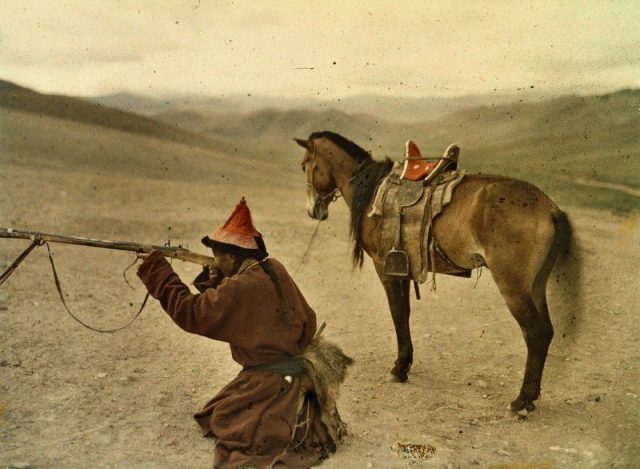

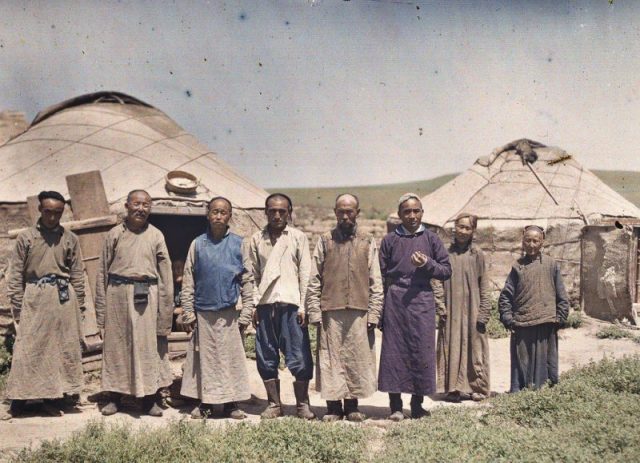

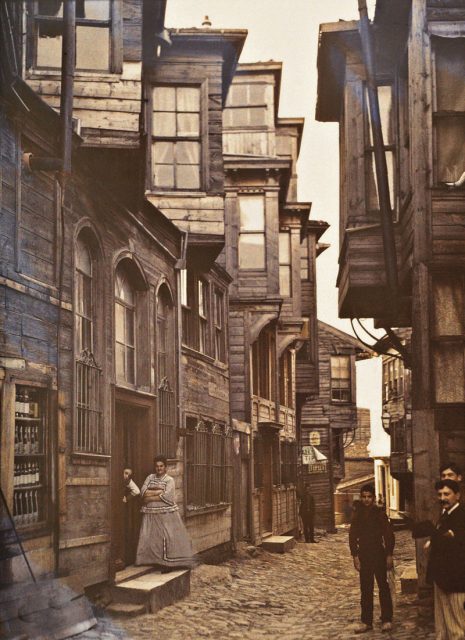

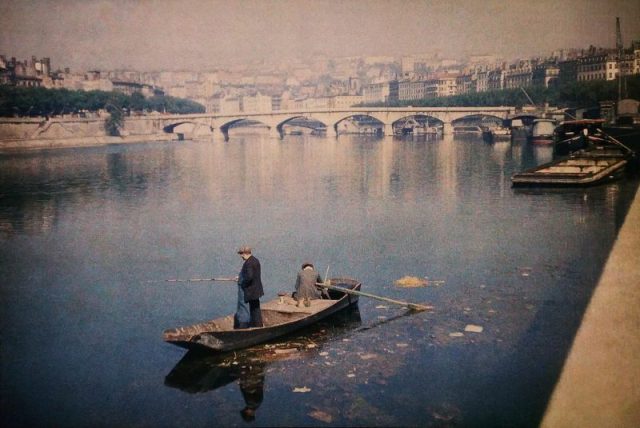

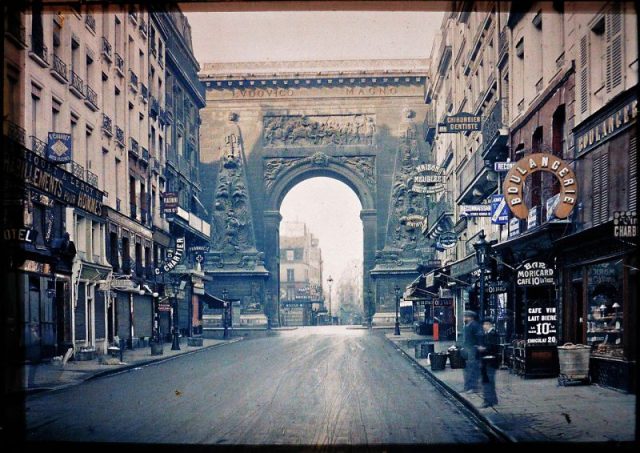

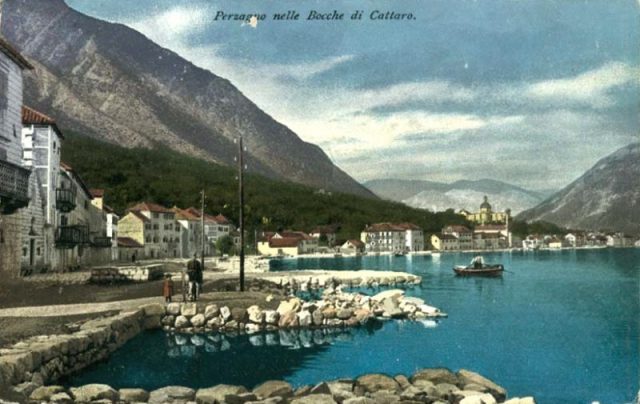

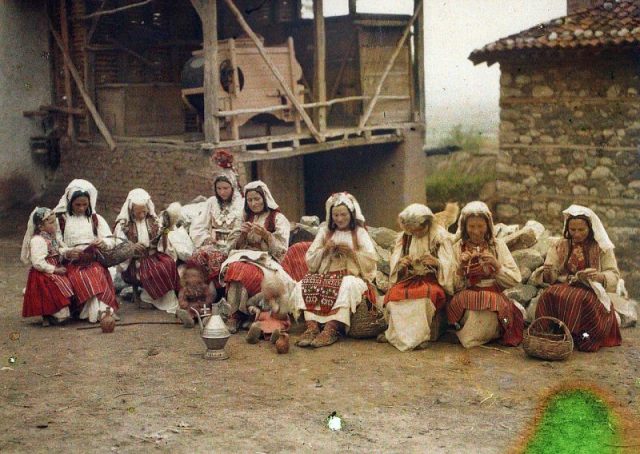

The Autochrome couldn’t come at a better time. As Europe progressed towards the First World War, photographers became keen on capturing everyday street life, monuments, architecture and folklore, tirelessly working on documenting the reality before them.

When the war came, they turned their eyes towards the home front, as well as the frontlines, creating an eternal record of the desperation, devastation and uncertainty during the years Europe spent in conflict.

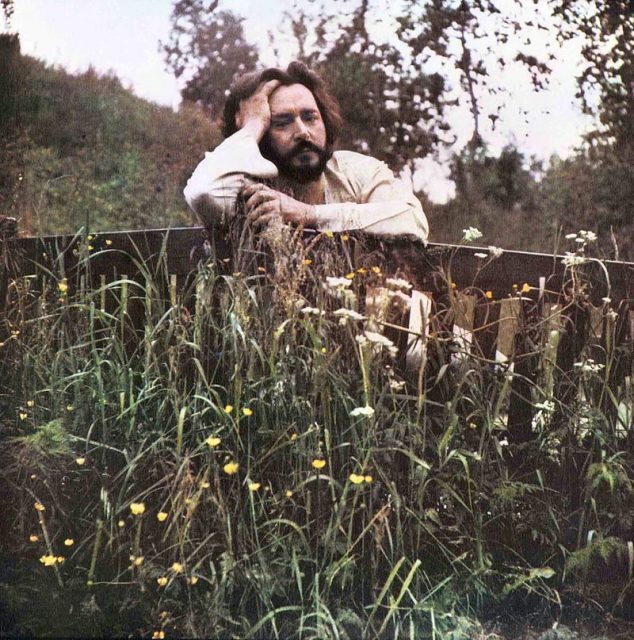

By the 1930s, Autochrome reigned supreme. However, with the invention of Kodachrome film in 1935, the popularity of the Lumiere’s patent quickly declined.

Although Kodak offered an alternative which was superior to Autochrome, in France, photographers continued to nurture their home product, with some even remaining loyal to the Lumiers until the 1950s.

Read another story from us: A Historic Look at the World Through the First Photographs Ever Taken

Kodachrome would be completely replaced by digital photography at the beginning of the 21st century, becoming as obsolete as its predecessor.