When producer Barry Navidi picked up the script for a comedy called Divine Rapture, he thought he had a hit on his hands.

Convinced of its box office potential, he spent several years trying to get it made. By the mid-Nineties the film was up and running, with an all star cast and an idyllic Irish location.

It all looked so promising. Yet Navidi’s dream ended in tatters and the village Hollywood appropriated to shoot their latest offering was left high and dry. How had things fallen so far from such lofty beginnings…?

The 1950s-set screenplay, written by Glenda Ganis, “had a mischievous twinkle that recalled Ealing comedies” according to a Guardian piece looking back on the production in 2009.

The Independent outlined the story in 1995, which “centred on a priest… who was convinced a miracle had occurred after a machinist in the lingerie factory… who died during love-making, came back to life at her funeral.”

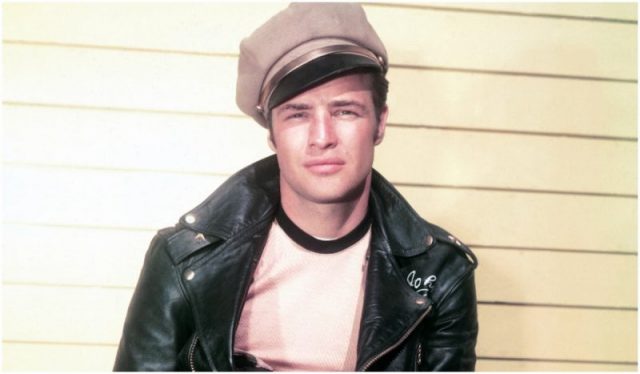

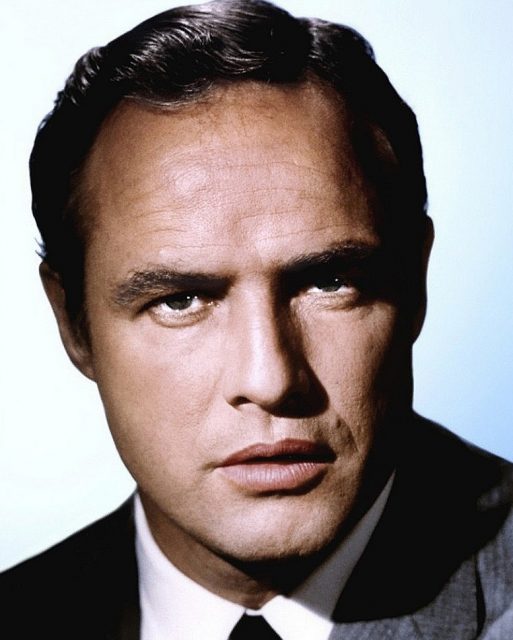

Debra Winger (Terms of Endearment) was cast as the deceased stitcher. This news was impressive enough, yet bigger fish were to land when it came to the male leads. None other than Marlon Brando was signed up as the priest.

The definitive method actor’s interest in the project was a deeply personal one. Believing he might have roots in the Emerald Isle, he indicated he could conceivably take Irish citizenship off the back of the movie.

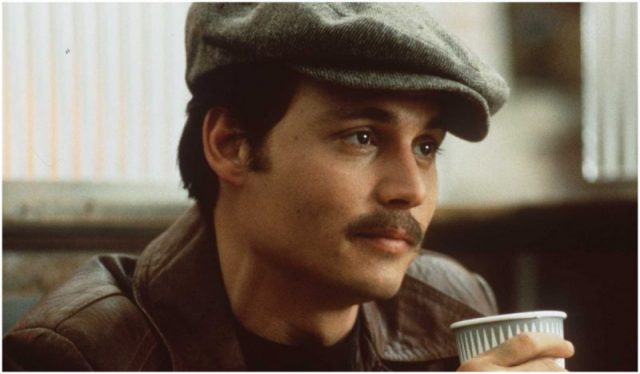

With one acting legend on board, it didn’t take much to attract another major name. Johnny Depp made Don Juan DeMarco with Brando in 1994 and jumped at the chance to collaborate again.

The Belfast Telegaph wrote in 2009 that “Depp agreed to work for a reduced salary just for the chance to feature alongside Brando.” Depp would play a reporter following the strange events in Divine Rapture’s fictional community. Also joining the cast was John Hurt.

Ballycotton, described as “stunningly situated at the southern tip of a 10-mile wide glassy blue bay in County Cork” by the Independent, was selected as the location. Locals were welcoming of their wealthy visitors, and some were hired for the production in various capacities.

Director Thom Eberhardt (Night of the Comet) soon found that Brando had some rather offbeat ideas on how to play his character. The Guardian mentioned how, soon after his arrival, “Brando phoned Eberhardt asking if they could meet at 11 pm.”

Eberhardt picked up the story. “I said, ‘No, Marlon, I’m too tired. I’ve been rehearsing all day.’ Then he said, ‘I’m going to shave my hair off and wear an orange wig’. Panic set in: ‘Get me a car!’ As I pulled in, the hair and makeup people were leaving. This guy comes down the stairs looking like a d*** with ears. Bald as a buzzard.”

Related Video: Vintage Celebrity TV Commercials

The star was known for his challenging behavior, but despite this Divine Rapture could have succeeded. Unfortunately its failure can be put down to that most common of movie hiccups… cashflow.

Budgeted at $12 million, Navidi used a company called CineFin as investors. While the arrangement seemed respectable enough, CineFin had been in hot water with the Feds over what were referred to as “alleged banking improprieties” involving its associates.

It became clear the funds simply weren’t in place. Everything began to unravel when “Winger’s agent went to collect her fee from CineFin’s escrow deposit company in Los Angeles, only to discover a parking lot at the given address.”

Divine Rapture shut its cameras off two weeks into the shoot. Just over 20 mins of footage was in the can.

A mortified Winger decided to offer villagers money out of her own pocket. “You don’t do this to people,” she was quoted as saying. “I couldn’t stand the thought that this is what showbusiness does.”

Brando returned home, having already received $1 million (his fee was to have been $4 million). The issue of his citizenship went up in the air, along with his plane.

Ballycotton took a financial hit from this outrageous fiasco, though the community took away some interesting memories from their time in the spotlight.

Talking to the Independent, fisherman John Roberts revealed what it was like being in the orbit of major movie stars. “One woman from London who was mad into Marlon Brando came over for five days,” he said. “She persevered and persevered day after day so she could just shake hands with him… Then we had to keep back hundreds of teenage girls when Johnny Depp arrived. That was very tough work!”

There was controversy of a different sort when the Bishop of Cloyne, Dr. John Magee, “forbade the use of the village’s Catholic church, so confessional booths were installed in a deconsecrated Protestant one just down the street.”

Documentary Ballybrando (2009) immortalized events behind the ill-fated film, and in 2012 producer Navidi made an attempt to mount the production again with a different cast, this time under the title of Holy Mackerel. If he’d gotten his way, Ballycotton would have been the setting and amends duly made.

Depp went on to take part in another movie that ultimately went unfinished — Terry Gilliam’s original version of The Man Who Killed Don Quixote (2000). That too had an accompanying documentary, Lost In La Mancha, which followed two years later.

It’s hard to tell if Divine Rapture would have set the box office alight. As things stand, it became famous for the wrong reasons. The residents of Ballycotton know it by another name… “Divine Rupture”. Perhaps one day Navidi will complete the picture and plug the gap on his CV.