Scientists have just named an ancient shark after an 80s video game, and it’s not just any ordinary shark. Its tiny fossilized teeth were found in the rock leftover that once contained the remains of Sue, the iconic T.Rex which remains the biggest and most complete fossil of its species so far found.

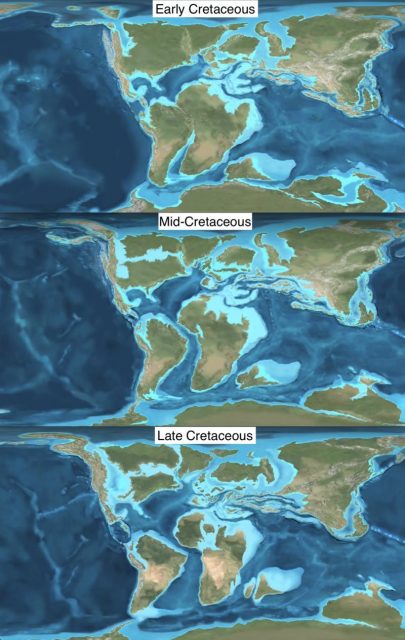

The extinct shark would have traversed the rivers and wetlands of South Dakota, USA some 67 million years ago. The new find, dating to the late Cretaceous period, has been recently presented in the Journal of Paleontology.

“The shark lived at the same time as SUE the T. Rex, it was part of the same world,” said Pete Makovicky in a press release statement, one of the study’s authors and also a curator at the Field Museum in South Dakota where Sue is permanently exhibited.

Most of the shark’s body was not preserved as “sharks’ skeletons are made of cartilage, but we were able to find its tiny fossilized teeth,” Makovicky said.

The teeth, of which about two dozens were retrieved, are each “only a millimeter wide–about the diameter of the head of a pin–and the shark they belonged to was small too,” he said.

“To the naked eye, it just looks like a little bump, you have to have a microscope to get a good view of it,” added Karen Nordquist, also from the Field Museum, who in fact first noticed the fossils in the remnants of Sue’s sediment.

The look of the teeth was impressive enough–resembling that of the player-controlled, space fighters from the memorable 80s video game Galaga. Altogether with the name of its finder, this inspired the research team to devise the species’ scientific name as Galagadon nordquistae.

The relatively small creature would have measured in between 12 to 18 inches and has been linked with modern-day carpet sharks like the bamboo shark and the wobbegong. It’s also intriguing that these analagous sharks today occupy waters mostly in the southeast Asia and Australia regions, and the Galagadon fossils showed up at a great distance from there.

“We had always thought of the SUE locality as being by a lake formed from a partially dried-up river–the presence of this shark suggests there must have been at least some connection to marine environments,” Makovicky said.

The extinct creature would have needed such water connections to end up in the Cretaceous rivers of South Dakota, the very same in which Sue waded through.

Galagadon nordquistae likely had a face that was flat and capabilities to camouflage well, perhaps similarly to its present-day relatives. With its tiny but strong teeth, it would have broken the shells of crayfish or snails, its major source of food.

Fossilized shark teeth remain to be the single greatest source of information for paleontologists to determine characteristics of lost species within this wide-spun marine, predatory family. The Galagadon find is the latest testament to that. Upon discovery, the team compared the teeth from the new find with other shark species, both living and extinct, to reach conclusions.

More than that, sharks remain among the most resilient creatures to have ever roamed planet Earth. Their fossil record is abundant enough as the oldest specimens of prehistoric sharks date back to some 450 million years in time.

Since then, sharks have made it through all known massive extinction events, including the one with the greatest amplitude of all. Roughly 252 million years ago, perhaps after a supervolcano erupted and acid rain fell from the skies, 90% of all life that lived on earth subsequently perished.

Only 5% of sea species were saved. The event known as the Great Permian extinction is less known than the Cretaceous extinction which claimed dinosaurs roughly 65 million years ago. Regardless of the case, sharks have always made it.

It is exactly their great ability to survive that has helped their kin reign at the top of the marine predators list and haunt the seven seas forever.