Thanks to a nine-year-old boy who tripped over a rock while following his dog, scientists made a discovery that they are now convinced is the “missing link” in human evolution.

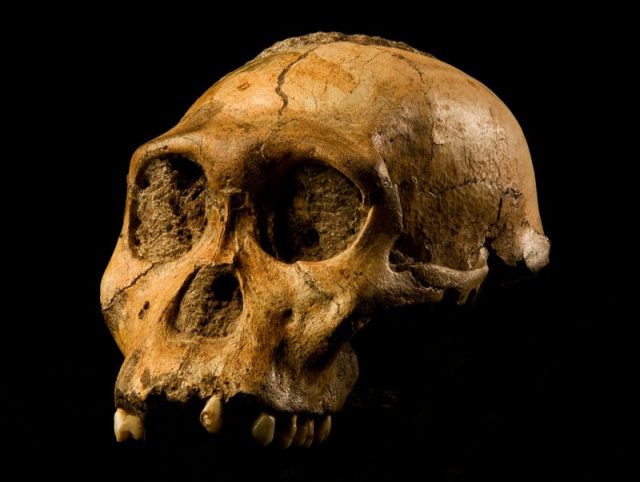

The fossils of Australopithecus sediba were found in 2008 after the boy, Matthew Berger, stopped to examine the rock he tripped over in what is now called the Malapa Fossil Site in South Africa.

It turned out it was a human bone and there were two partial skeletons there. The skeletons are now under the custodianship of the University of Witwatersrand.

Each partial skeleton is more complete than the famous “Lucy,” an early hominin species found in 1974 in Ethiopia.

After 10 years of careful study, a new report has announced that the two skeletons are of the same hominin species and that species is likely to be the proverbial “missing link” – the transitional species that became the first humans.

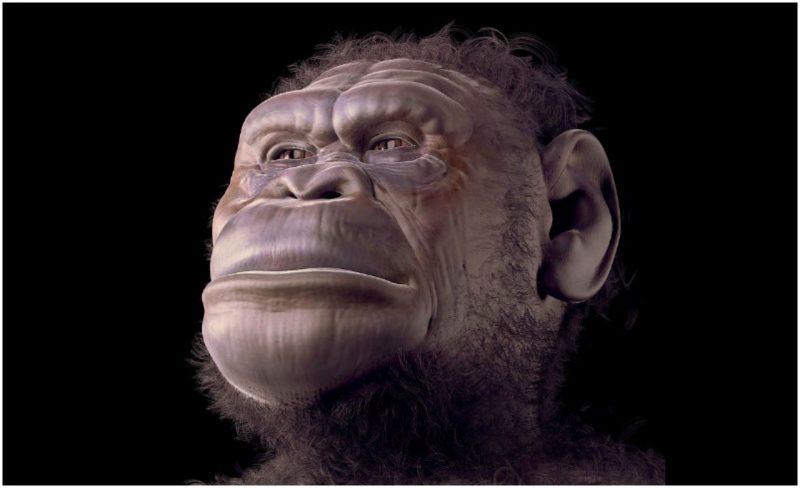

The study, which describes the new species’ anatomy in detail, found that Australopithecus sediba is unique, but shares similarities with its neighbor Australopithecus africanus and early members of the genus Homo, “suggesting a close evolutionary relationship.”

If it’s true, that transition occurred much later in history than previously believed. The partly fossilized 2-million-year-old bones were of an adult female and a juvenile male.

“Researchers discovered that the Australopithecus sediba species is closely related to the Homo genus and fills a key gap in the chain of human evolution between early humans and our more apelike ancestors,” according to USA Today. “The fossils are distinctive yet similar to species along the same timeline, according to researchers.”

Australopithecus sediba was well adapted to terrestrial bipedalism–or walking on just two feet–but also spent “significant time climbing in trees, perhaps for foraging and protection from predators.”

At the same time, Australopithecus sediba’s hands have grasping capabilities, which suggests that the species may also have used tools.

“Our findings challenge a traditional, linear view of evolution. It was once thought that a fossil species a million years younger than Lucy would surely look more human-like,” explained Jeremy DeSilva, an associate professor of anthropology at Dartmouth and co-author of the study, in a press release.

Photo by Brett Eloff. Courtesy Profberger and Wits University CC BY SA 4.0

“The anatomies we are seeing in Australopithecus sediba are forcing us to reassess the pathway by which we became human,” said DeSilva.

“Australopithecus” means “southern ape,” a genus of hominins which lived between around 4 and 2 million years ago.

This discovery set off debate among scientists, with some rejecting the idea that they were from a previously undiscovered species with close links to the homo genus and others floating the idea that they were from two different species altogether.

Photo by Durova -CC BY-SA 4.0

“Imagine for a moment that Matthew stumbled over the rock and continued following his dog without noticing the fossil,” the scientists wrote in their study. “If those events had occurred instead, science would not know about Au. sediba, but those fossils would still be there, still encased in calcified clastic sediments, still waiting to be discovered.”

The Lucy skeleton finding was momentous to an earlier generation. Lucy was found on November 24, 1974, at the site of Hadar in Ethiopia. Two scientists had taken a Land Rover out that day to map in another locality. After a morning of surveying for fossils, they decided to head back to the vehicle.

Johanson suggested taking an alternate route back to the Land Rover, through a nearby gully. Within moments, he spotted a right proximal ulna (forearm bone) and quickly identified it as a hominid. Shortly thereafter, he saw an occipital (skull) bone, then a femur, some ribs, a pelvis, and the lower jaw.

Two weeks later, after many hours of excavation, screening, and sorting, several hundred fragments of bone had been recovered, representing 40 percent of a single hominid skeleton. named Lucy.