Today, almost none of us could imagine waking up in the morning without the sound (and for many of us the multiple snoozing) of the alarm clock placed on our bed table.

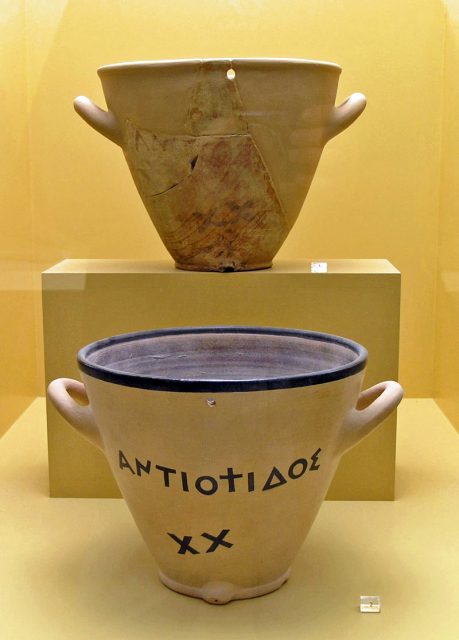

The earliest known alarm clock was invented by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (428–348 BC). Tired of students, and himself, arriving late to the academy because of oversleeping, his solution was to make some novel adaptations to a water clock. These were used to measure the passing of time by allowing water to drip via a small hole from one vessel to another. By the addition of a simple tube, Plato’s clock siphoned all the water very fast into one final vessel which was enclosed except for thin openings. As the air was pushed out, the alarm went off with a sound like a whistling kettle.

Another Greek, Ctesibius (285–222 BC), known as the Father of Pneumatics, took Plato’s water alarm clock idea and ran with it. Ctesibius’ clepsydra, or “water thief,” sounded a gong by dropping pebbles onto it at the appointed time. A more accurate clock would not be invented until Christiaan Huygens came up with the pendulum clock in 1658.

In China, a Buddhist monk and astronomer named Yi Xing created the first mechanical clock in 725 AD, although this was still powered by water. In addition to striking a bell every hour, this clever machine was also an astronomical clock that indicated the time of sunrise and sunset, and the cycle of the moon.

Levi Hutchins from New Hampshire was the first person to patent a modern alarm clock in the U.S., in 1787. His invention was prompted by the need to get up at 4:00 am for his strict work regime.

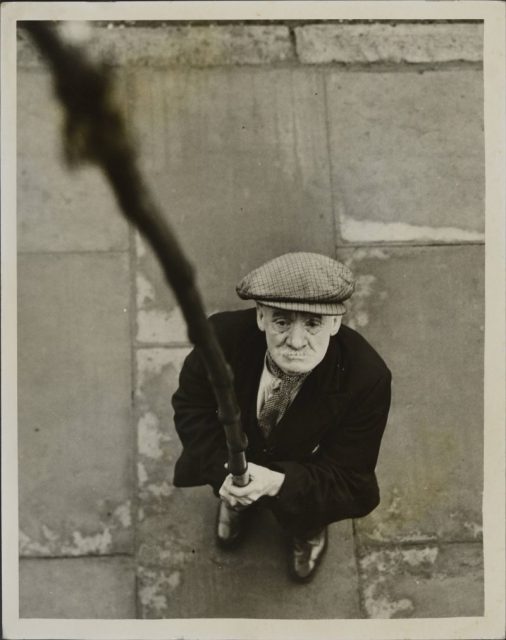

Considering these advances in clock technology, it may come as surprise to learn that up until the 1970s in some areas in Britain, especially in the northern mill towns and cities that have docks, workers were woken by a tapping at their bedroom window.

The people who did the tapping were known as “knocker ups” or “knocker uppers.” They walked the streets from early in the morning, tapping on the windows of their sleeping customers — usually men who worked shifts or odd hours — with a long pole. Alarm clocks were neither affordable nor reliable, but the knocker up was.

In an interview for Lancashire Mining Museum, artist Paul Stafford shared his memories of the knocker ups who woke up his parents in their family home in Oldham, Manchester when he was young.

Stafford recalls: “The knocker upper wouldn’t hang around either, just three or four taps and then he’d be off. We never heard it in the back, though it used to wake my father in the front.” Some knocker-uppers also used rattles, soft hammers or pea shooters. Of course, many may wonder: Who woke up the knocker-up?

This question gave rise to a popular tongue-twister that goes:

We had a knocker-up, and our knocker-up had a knocker-up

And our knocker-up’s knocker-up didn’t knock our knocker up, up

So our knocker-up didn’t knock us up ‘Cos he’s not up.

Knocker ups were highly aware of their importance for the workers and made sure their effort paid off economically. To begin with they would simply knock loudly on the front door, however neighbors of the workers who ordered waking up often complained of being disturbed.

Realizing that many who didn’t pay for the service were also receiving it, the knocker ups modified a long stick which was loud enough to wake the respective client but not to disturb his sleeping neighbors.

In 1878, according to Lancashire Mining Museum, one Mrs Waters explained her trade to a reporter for the Huron Expositor. Customers paid a weekly fee that was “reasonable and usually based on how far the knocker-up had to travel and the time of day the person needed to be awakened.”

“Mrs. Waters claimed ‘she never earned less than thirty shillings a week; mostly thirty five; and … as high as forty shillings a week.’ ” This was a remarkably good income, especially for a woman. For comparison, a skilled sewing machinist working long hours in a mill is unlikely to have been paid more than 16 shillings per week.

Knocker ups were always in demand in larger industrial towns like Manchester, so many people supplemented their income by moonlighting as human alarm clocks. Sometimes, this duty was considered even more important than urgent community policing.

As reported by the Lancashire Mining Museum, the man who discovered the first victim of Jack the Ripper in Buck’s Row, Whitechapel, alleged that he immediately informed a policeman — who practically ignored the man’s cry for help due to his own knocking-up duty.

Read another story from us: Oldest Periodic Table in Existence Found While Cleaning a Scottish Lab

Some families of knocker-uppers passed on the trade to the next generation, however, by the 1950s, knocking-up had all but vanished due to affordable alarm clocks and electricity. The last knocker-up was from Bolton and he retired in 1973.