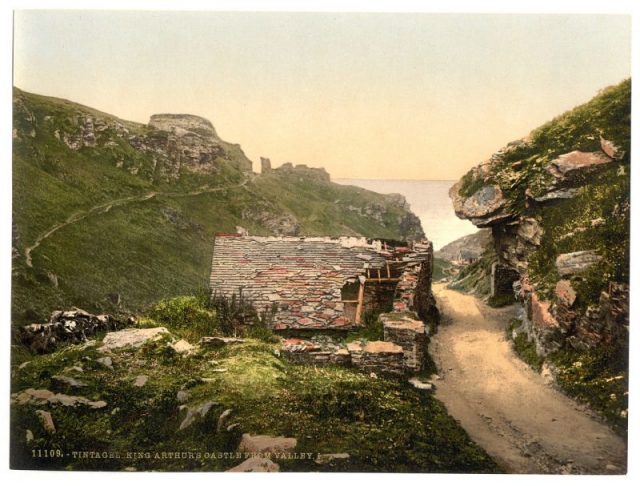

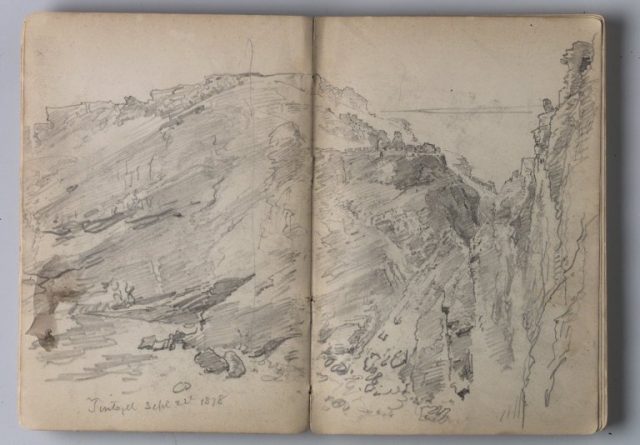

A windswept headland off the Atlantic coast of Cornwall, Tintagel is a land shrouded in myth. Associated with the legend of King Arthur since the 12th century, the ruined castle which clings to the dangerous-looking crag entices visitors across a dramatic footbridge to drink in a landscape that wouldn’t seem out of place in Game of Thrones or Lord of the Rings.

Tintagel Castle was built in the early 13th century by Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall — the younger brother of King Henry III of England and one of the wealthiest men in Europe. Lacking in any strategic value and constructed in a style that was purposefully out of date, Richard was deliberately bringing a lost legend to life.

IDS photos CC BY-SA 2.0

The English cleric and chronicler Geoffrey of Monmouth conjured up the Arthurian connection to Tintagel in his 1136 epic Historia regum Britanniae, or The History of the Kings of Britain. He claimed that his book, which connected England’s historical monarchs to mythical monarchs like King Arthur, was a Latin translation of an older text but much of it was Monmouth’s own elaborate fantasy.

Even within his lifetime scholars were crying “fake history.” Sometime around 1190, the historian William of Newburgh wrote that “it is quite clear that everything this man wrote about Arthur and his successors […] was made up, partly by himself and partly by others”

More recent studies have shown that Historia regum Britanniae can be traced to a number of earlier sources cherry-picked by Monmouth, from semi-mythical Welsh histories — which like Cornwall was a hold-out for the Celtic languages and legends that covered Britain prior to the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons — to local folklore and oral histories.

There’s no doubting geography played a part too. At the time of Monmouth’s writing, Cornwall was far from the center of English power. Although its local lords had been brutally suppressed following the Norman Conquest and their lands given over to the new Norman aristocracy, the Cornish still spoke their own language — a Celtic tongue closely related to Welsh and Breton — and maintained their own traditions.

Furthermore, the landscape was dotted with Iron Age hill forts, standing stones, and other reminders of an ancient culture, that stirred the imaginations of Anglo-Norman travelers.

Monmouth establishes the fortress of Tintagel as the site of Arthur’s conception, where his father Uther Pendragon uses a magic potion to assume the form of Gorlois of Cornwall in order to infiltrate his castle and sleep with Gorlois’s wife, Igraine.

Later writers upgraded it to the site of Arthur’s birth, as well as the seat of King Mark of Cornwall in the epic romance Tristan and Iseult — a sort of Celtic Romeo and Juliet that like the story of King Arthur, emerged in the 12th century and quickly captivated Medieval audiences.

Monmouth described the fictional fortress Gorlois of Cornwall in detail, writing that, “The castle is built high above the sea, which surrounds it on all sides, and there is no way in except that offered by a narrow isthmus of rock. Three armed soldiers could hold it against you, even if you stood there with the whole kingdom of Britain at your side.”

The castle that now stands in romantic ruin at Tintagel may have been built as a reflection of Monmouth’s fantasy, but in this case Monmouth’s fantasy was the echo of older history.

Historians dislike the phrase “Dark Ages” yet it is a commonly accepted term. It reflects a time when the history of Western Europe between the collapse of Roman rule (which ended around 410 AD in England) and the later Medieval era was little understood (in England this was thought to end in 1066 with the Norman Conquest).

In this outdated view of early Medieval history, following the retreat of Roman civilization the continent regressed into a state of barbarism and ignorance where nothing changed or developed. Put simply, because culture wasn’t written down nobody thought it existed.

It is in the Dark Ages that the mythical King Arthur was said to have reigned, maintaining order over an island nation of civilized “Romanised” Britons and fighting off cruel and warlike Anglo-Saxon invaders.

Through archaeology and careful study of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and other early Medieval sources we now know much more about these murky centuries than our predecessors did — and what it tells us is that there was an important fortress at the site of Arthur’s legendary birthplace.

Over the last few decades, archaeologists have increasingly found signs of a wealthy — most likely royal — settlement at Tintagel. The island was covered in simple houses that could shelter over 300 people, and the land-bridge was made narrower and more dangerous by the digging of defensive earthworks. There were no need for high walls when the unpredictable ocean and the jagged rocks can do the job for you.

Tintagel may have been one of the strongholds of the kings of Dumnonia, a Celtic kingdom which largely resisted the Romans and held out against the Anglo-Saxons in part until the 9th or 10th centuries. At the height of its power and prestige, Dumnonia covered a 150-mile stretch of southwestern England from Cornwall to the modern counties of Dorset and West Somerset.

The Dumnonii kings didn’t have a fixed home, but moved around their domain and Tintagel may have been one of their compounds — a secure location to wait out war or other dangers.

Whoever lived there was certainly immensely wealthy. Pottery found by digs on the headland suggests that Tintagel was at the end of a trade network that followed the French and Spanish coast down to North Africa and along the Mediterranean Sea to Greece, Turkey and the Near East — then parts of the Byzantine Empire.

The pottery remnants recovered at Tintagel so far are greater than the total finds of Eastern Mediterranean trade goods in the rest of Britain and Ireland combined — and so far only 5 percent of the site has been properly studied by archaeologists.

By the 13th century, the “new” castle of Tintagel was already crumbling, its location making it altogether too vulnerable to the elements, and eventually the gatehouse collapsed into the rolling waves.

The Earls of Cornwall who followed Richard didn’t share his enthusiasm for the folly and it was left in the hands of a skeleton staff before being abandoned sometime in the 15th century — but the legend of King Arthur ensures that it’ll never be forgotten.

While there’s no historical evidence for King Arthur, let alone evidence that actually connects him to Tintagel, archaeology reminds us that this incredible island still has a great many secrets left to tell of lost Dark Age kingdoms, warrior kings, and incredible riches.