The Vindolanda garrison area in northern England, once a distant outpost of the immense Roman Empire, is one of the most intriguing archaeological sites in the U.K. Ever since the discovery of writing tablets in the area back in the 1970s (the tablets now voted as Britain’s Top Treasure), archaeologists have repeatedly returned to Vindolanda in search of more artifacts. They have rarely been disappointed.

As of more recently, an excavation effort in 2017 uncovered thousands of artifacts dated to the early second century AD. Most intriguing, the treasure trove contained two iron swords, exceptionally well-preserved.

The swords resurfaced along with an array of other military and personal items that belonged to Roman soldiers and their families such as “cavalry lances, arrowheads and ballista bolts,” according to the Guardian. Add to those everyday items like “combs, bath clogs, shoes, stylus pens, hairpins and brooches.”

More tablets were also dug out, as well as some dazzling copper alloy fitments for saddles, straps, and harnesses. Given the abundance and remarkable preservation of the finds, archaeologists have compared this unexpected dig to “winning the lottery.”

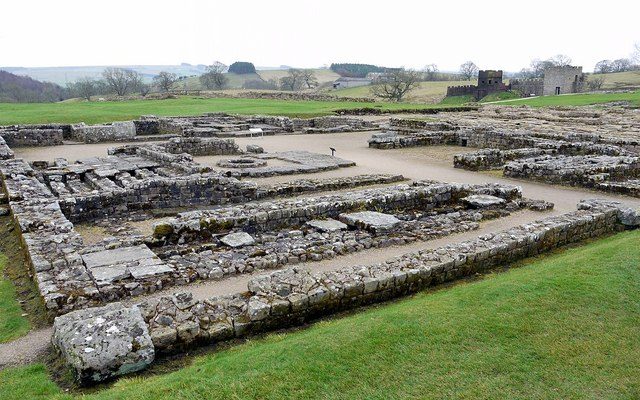

The Vindolanda site lies a short distance to the south of Hadrian’s Wall and near the market town of Hexham. For the ancient Romans, it was “a key military post on the northern frontier of Britain,” according to the Roman Vindolanda Museum. The earliest wooden fort was erected around 85 AD, predating the building of Hadrian’s Wall (122-128 AD). This was replaced with a stone fort after the completion of the wall — the ruins that can be seen at Vindolanda today are of a later fort dated to the 4th century.

The recent finds were sealed beneath a layer of Roman concrete, a notoriously durable building material, that was laid down when the first stone fort was built. It left the artifacts in oxygen-free soil, thus protecting them from degradation.

Of the two cavalry swords, one was found complete, albeit bent at the tip. It was found in a living room corner in the barracks and could have been retired by its owner. The second sword showed up in a room next door, almost complete as its handle and scabbard were missing. Since the costly weapons must have been prized to their owners, it’s puzzling to think of why they were left behind.

Comments by archaeologists say that finding the swords this way is comparable to finding the rifles of modern soldiers left in negligence, regardless whether the rifle is still being used.

Along with the real swords, the team on the field also came across two 2,000-year-old toy swords made of wood.

“The excavated rooms included stables for horses, living accommodation, ovens and fireplaces,” a press release from the Vindolanda Trust describes the barracks, which could have sheltered 1,000 people.

The first sword was found by a volunteer, as “the earth surrounding the object was slowly pulled back under careful supervision to reveal the tip of a thin and sharp iron blade, resting in its wooden scabbard.”

Dr. Andrew Birley, one of the senior archaeologists on board and son of Robin Birley who headed the team that discovered the famed Vindolanda writing tablets some 45 years ago, said that moment of the sword discovery was “quite emotional.”

“You can work as an archaeologist your entire life on Roman military sites and, even at Vindolanda, we never expect or imagine to see such a rare and special object as this,” he said.

Since the two swords originated from different rooms, archaeologists have assumed they were owned by different soldiers. Harder to determine is why the swords, like the rest of the usable items, were left behind in such a manner. One explanation could be that the garrison stationed there was forced to leave the premises in a great rush. The Roman soldiers consigned to serve at this far northern frontier of the empire had plenty of reasons to stay alert.

It is thought the barracks were deserted roughly two decades before Hadrian’s Wall was erected. The wall offered additional protection to the part of Britain administered by Rome against the Picts, who back then inhabited the territories of modern-day Scotland and parts of north England.

The soldiers also had to confront local native Britons who periodically rebelled against the presence of their continental tenants, especially around the period emperor Trajan died in 117 AD.

In this context, the barracks and its retrieved contents add to the history of the Hadrian’s Wall. The cavalry barracks and the weapons found indicate that Rome was strengthening its power in the region well before the wall was built. The times were turbulent.

Read another story from us: 4 Billion-Year-old Rock from Earth Discovered on the Moon

Meanwhile, new artifacts keep emerging from Vindolanda. A new research excavation that began in April 2018 unearthed a mysterious bronze hand that archaeologists have linked to the cult of Jupiter Dolichenus, one of the Roman “oriental” deities, which according to Britannica.com was “originally a local Hittite-Hurrian god of fertility and thunder worshiped at Doliche (modern Dülük), in southeastern Turkey.”

The diversity of artifacts that keep coming from the Vindolanda site is a testimony that the Roman soldiers lived a rich and intimate life, one greater than solely defending the borderline.