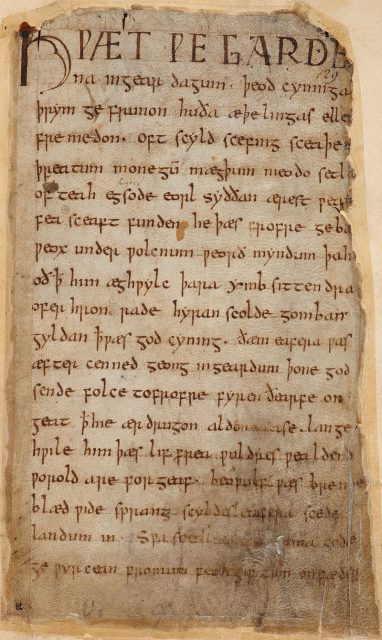

If you received an education from the American public school system, you will remember the tedious study of Beowulf during high school, but may not have taken the chance to appreciate one of the oldest remaining manuscripts in the English language.

You also would not have read the real Beowulf, but read a translation of the epic poem. It was written in Old English, an Anglo-Saxon language completely unintelligible to English speakers today.

Old English is most often incorrectly associated with the scholastic deciphering of Shakespeare. In reality, it dates back to the 5th century, eventually being replaced by Middle English after 1066, placing it two periods before the Bard. This ancient tongue was great grandparent to the Modern English we speak today.

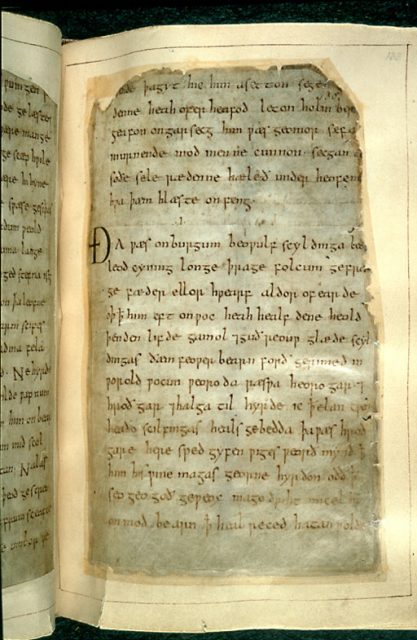

Fortunately, four primary sources of Old English poetry remain intact to this day. Along with the Beowulf manuscript, the Vercelli Book, the Junius manuscript of religious poems, and the Exeter Book have survived almost a full millennium.

The latter is the largest volume of Old English literature — be it poetry or prose — that still exists today. It was gifted to the Exeter Cathedral in 1072 from the bishop of Exeter upon his death.

The Exeter Book gives an in-depth look into medieval times as it contains the most varied collection of writing: along with an anthology of poems, the compilation also includes elegies (which back then were defined by more than just poems for the dead, subjects ranging across all human emotion) and, most interestingly: riddles.

There are just under 100 riddles in the Exeter Book, many of which have blatantly lewd hints. “I stand up in bed, hairy somewhere down below,” is arguably the most subtle line in Riddle 25, proving that bawdy humor is nothing new for the English language. Scribes were writing witticisms both pure and licentious from day one.

In these pages there lie more mysterious questions than “What am I?” Despite being fortunate enough to have these artifacts in their safekeeping, historians and linguistic specialists are unable to confirm the authors or the scribes who wrote them.

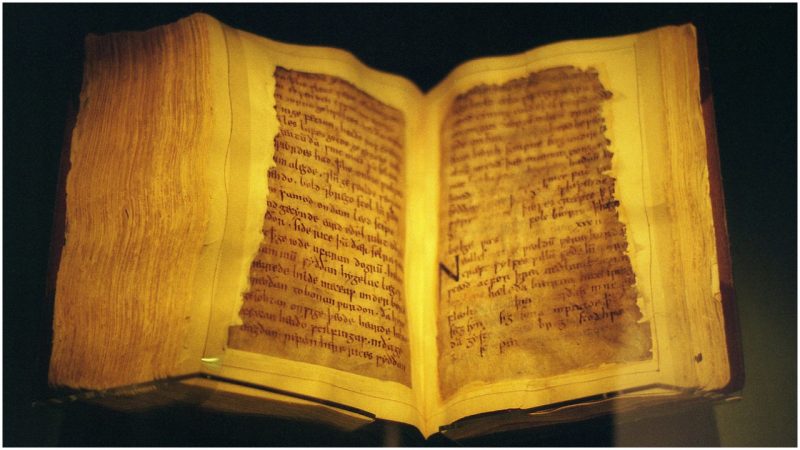

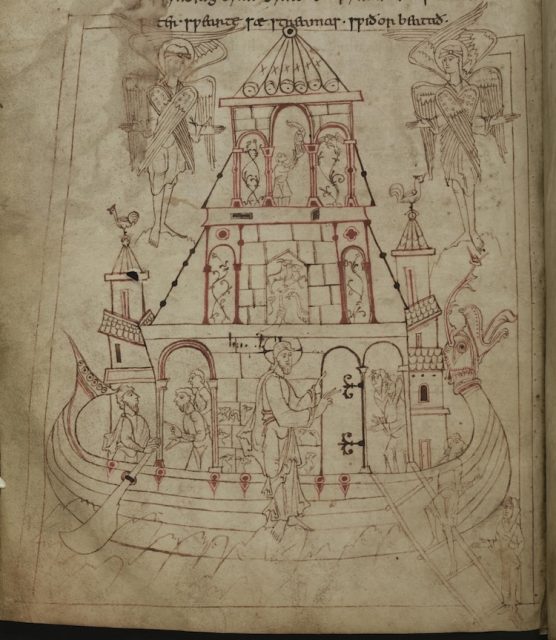

“Artifact” doesn’t even begin to convey a merited description of the texts, as the four codices each present themselves as an individual work of art.

A “codex” is what we call a book. To be precise: the composition of a book. Compared to a scroll, a codex is a collection of single sheets of paper bound together on one side. Because of the universally accepted form of books today, the term “codex” has evolved to imply a historical manuscript.

The effort put into these manuscripts in considerable. Each of the poems were written entirely by hand. Each illustration drawn freely, each letter carefully traced and filled in.

The unknown scribes had no other way to publish their manuscripts. Wood block printing already existed in China and Japan during the time of the Anglo-Saxons, but the technique wouldn’t make its way to Europe before the 14th century.

The movable type printing has a similar history. The attention to detail and dedication by the unknown craftsmen is obvious to anyone who sees these codices.

Along with Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, the Domesday Book, the Codex Amiatinus, and the Lindisfarne Gospels, the only remaining collections of Old English poetry are currently on display as part of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War exposition at the British Library in London until February 19th. It is necessary to book in advance and time slots are limited.

Thanks to the British Library, you can learn even more about the culture and society of Anglo-Saxon times with their new website (https://www.bl.uk/anglo-saxons).