Mary Ball Washington was quite the character. They say that behind every great man is a great woman…and, sometimes, a pill of a mother. Take George Washington, for example. America’s first president made his way across the Delaware River, froze his buns off at Valley Forge, and led the fight for America’s independence, yet was helpless when it came to controlling his own mom.

Mary Ball Washington was, if historians are to believed, something of a handful — a woman who got on her son’s last nerve and who no doubt had the big guy pulling out his powdered hair by the fistful.

Born in 1708, and orphaned at 13, Mary would marry British businessman Augustine Washington, a widower with four children, at age 23.

The couple would have five children of their own — four boys and a girl, George being the oldest. (A sixth child, a girl named Mildred, didn’t survive infancy.) Augustine would die just twelve years after they were married.

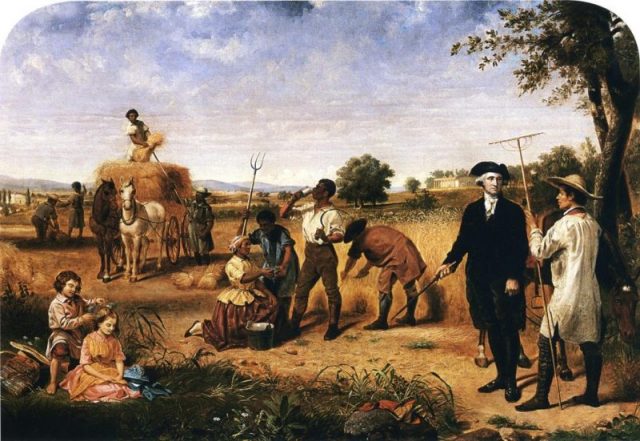

Unlike most women of the time, Mary never remarried and ran the property (Ferry Farm) herself while raising her young brood, with the help of a half-dozen slaves.

Formidable, to be sure. Particularly when it came to her firstborn — and most famous — son, George. After he inherited Mount Vernon from his father in 1754, he and his mother saw very little of each other, save for when business would take him to the Fredericksburg area. But make no mistake, Mary was still very much a part of Washington’s life.

Entrenched in the Pennsylvania backwoods, as an aide to General Edward Braddock during the French and Indian War, young Washington received a letter from his mother, informing him that she was in serious need of a servant and (wait for it) some butter. (You read that last part twice, didn’t you?)

An incredulous Washington would fire off a terse missive, which started off, “Honourd Madam,” and went on to say that he was “sorry it is not in my power to provide you with a Dutch Servant, or the Butter … you desire. We are quite out of that part of the Country where either are to be had, there being few or no Inhabitants where we now lie Encampd, & butter cannot be had here to supply the wants of the army.” (Basically, 18th century shorthand for “Yeah…that’s not gonna happen.”)

That, apparently, settled the matter. But a decade later, during the Revolutionary War, Mary was back in form, openly singing the praises of England’s King George III and the Loyalists — the very men her son was fighting against. And then, there was a little matter of her living arrangements.

In 1772, getting on in years, Mary was convinced by her children to leave Ferry Farm and move into a home that Washington had purchased in Fredericksburg, not far from his sister Betty. Though the place was modest, Washington took great pains to upgrade the two-acre property.

Imagine then his surprise, while deep in his battle with the Brits, he received word that his mother was complaining about her living arrangements to pretty much anyone who would listen, bemoaning that she “never lived soe poore in all my life.” Mary even went so far as to bring in the big guns, asking the Virginia state legislature for a pension.

This was too much. Upon learning that his mother was accepting handouts, Washington, a proud man who feared being “viewed as a delinquent, and considered perhaps by the world as [an] unjust and undutiful son,” wrote to one of his brothers, asking him to sniff around and suss out if her claims of poverty were legit — yet at the same time instructing him, “to represent to her in delicate terms, the impropriety of her complaints, and acceptance of favors, even when they are voluntarily offered, from any but relations.”

For good measure, he also wrote to a pal in the Virginia Assembly, making it clear that his mother, “has not a child that would not divide the last sixpence to relieve her from real distress. This she has been repeatedly assured of by me; and all of us, I am certain, would feel much hurt, at having our mother a pensioner, while we had the means of supporting her; but in fact she has an ample income of her own.”

Mary lived to the ripe old age of eighty-one, succumbing to breast cancer in 1789. Washington would see her one last time before traveling to New York for his inauguration.

Mary would die four months later and was buried near Kenmore, the home of her daughter Betty and her husband Fielding Lewis — just a heartbeat away from Meditation Rock, a place Mary often spent time reading and praying for her son’s safe return during the Revolutionary War.

Read another story from us: George Washington’s Bizarre False Teeth

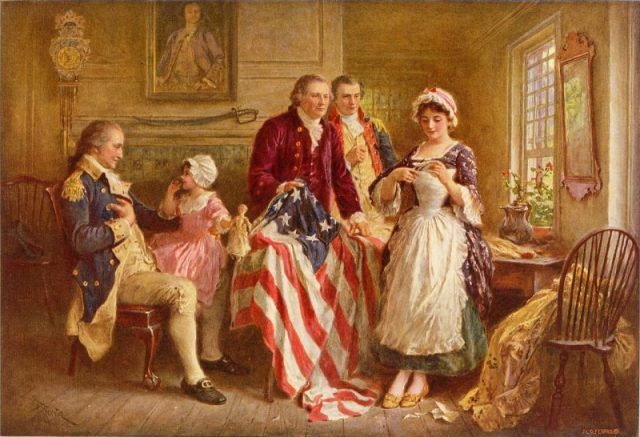

Today, a tall granite monument, built with money raised by the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution, stands at the gravesite. Fittingly, for the mother of the Father of Our Country, the Mary Washington Monument is the only monument in the United States erected to a woman by women.