Death was a prevalent discourse during the life and times of average Victorians. One rather obvious reason was that life expectancy was much shorter. Be pleased with yourself had you lived in 19th century London and reached the advanced age of 45.

Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, a vigorous man who succumbed to a fever, was not as lucky and died at the age of 42. The sad event, which occurred on a cold December night in 1861 at Windsor Castle, would define the rest of Queen Victoria’s days as Britain’s reigning monarch.

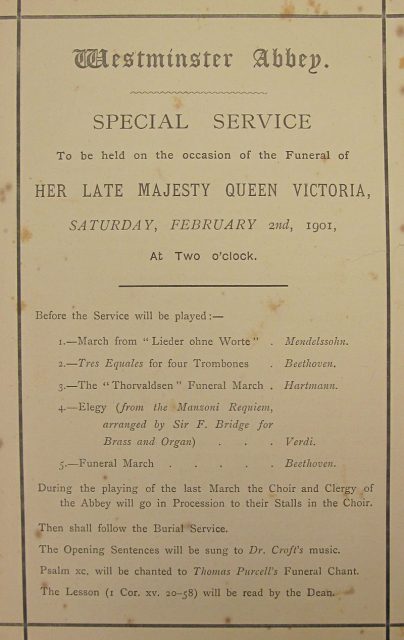

She would clothe herself in black up until the end of her own life some four decades later. Queen Victoria died on January 22, 1901 at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight and her funeral, which ended the era that claimed her name, is a story on its own right.

Once the Queen realized her time was running out, she reportedly called for her personal physician, who catered to her during the last 15 years of life — Dr. James Reid.

The doctor became a chosen confidant. Now at the end, he would bear the grave responsibility of conducting everything contained in the detailed 12 pages the Queen had prepared. The document described what should be done once her body turned cold.

As you might imagine, those instructions were kept secret. First and foremost because the Queen’s own children would have quickly denounced what stood written in her instructions. The document resurfaced years later in Dr. Reid’s family archives.

Dr. Reid assured that the instructions were fully implemented, including the list of rather bizarre items that were supposed to go in the coffin along with the Queen’s body.

The abundance of flowers, gathered and brought from all around the U.K. and abroad, helped some of those items go unnoticed.

So, what exactly did the longest reigning monarch of Britain at the time want to conceal?

These were mostly items of sentimental value for the Queen. One included a plaster cast of Prince Albert’s hand. It’s weird enough that the Queen actually kept a plaster hand of her dead spouse. Even weirder is that she slept with it for years after his demise. But that just one bit of all the weird.

The Queen’s grieving observations are known to have included requests to servants that each morning they bring hot water and the shaving set that belonged to Prince Albert, as if he was still there. This uncanny practice supposedly went on for years.

While the Queen didn’t ask for the shaving set to be placed in the coffin, she did ask for the prince’s dressing gown. The gown was placed above a layer of charcoal added to neutralize the smell of decay and she would lay atop of it.

Queen Victoria, perhaps surprisingly, also demanded a wholly white funeral. This would include white horses for the military processions that were arranged to carry her casket, with matching mourning attire and all.

Even more notably, the most famous widow in history wanted to be laid to rest with the white veil she wore on her wedding day in 1840. Such a wish entirely contrasted with the outfits the Queen opted for after the death of her late husband, but it was symbolic in several ways.

Queen Victoria pioneered the white wedding gown, setting the trend for generations to come. Before that, different colors were worn by brides for wedding ceremonies. The Queen was definitely attached to her bridal clothes. She would have the veil in the coffin both to hint at the chastity of her youth, and to honor the one most significant — and satisfying — relationship she experienced in life.

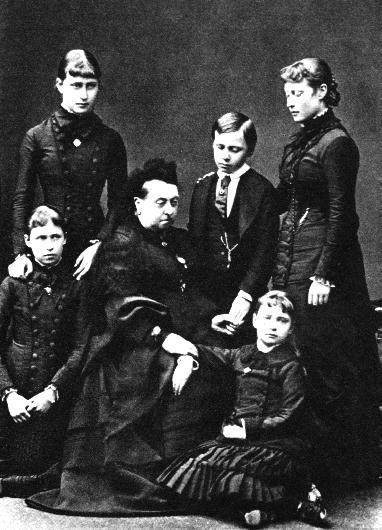

In the coffin, Queen Victoria also asked for a cloak which Princess Alice had embroidered for her father. Princess Alice, one of the nine children born to Victoria and Albert, was their third-born and she had forged a special bond with her parents. She is said to have taken care of Albert during his sickness, offering support until his very final moments. She was again there for her grief-stricken mother.

Since the Queen was overwhelmed by the loss, for a while Alice would step up as a personal assistant, replacing her mother for much of the ongoing royal duties.

It’s understandable that Victoria later developed an attachment for that particular embroidered cloak. Princess Alice was also the first of her children to pass away, aged only 35. The garment became a memory-preserving item, both of the Queen’s favorite child and of her loving spouse.

On her hands, the lifeless Queen Victoria wore an excessive amount of jewelry, something which critics have associated with occult practices (the presence of Albert’s embroidered cloak or his dressing gown in the coffin have also been connected with occultism).

But two pieces of jewelry stand out in importance: Queen Victoria’s wedding ring, and a second ring placed on the same finger that was given to her by her supposed lover, John Brown. Here begins the part where the Queen probably needed Dr. Reid’s help the most.

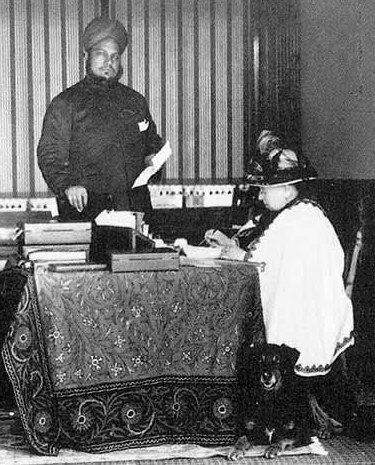

Brown was a royal family servant from Scotland and who comforted the Queen following the Prince Albert’s death.

For other royal family members, this affiliation screamed scandal, however. The close relationship that developed between the Queen and her servant was not approved of. To such a degree that her son and successor to the throne — Edward VII — made sure to discard all memorabilia associated with John Brown. (Probably equally loathed was the Indian servant Abdul Karim, with whom Victoria became close after Brown’s death).

Thanks to the good doctor, Queen Victoria still carried a lock of John Brown’s hair and a photo of him to her grave. One of her fingers indeed was adorned with a ring that had originally belonged to Brown’s mother. Many of these sentimental items found their way into the coffin moments before it was sealed.

Only one request by the Queen was not carried out — that a life-size sculpture of her should be moved to the mausoleum at the Frogmore Estate, which housed a matching sculpture of Albert, as well as his remains.

The mausoleum and the sculptures were commissioned by the Queen shortly after Albert’s death. While Albert’s sculpture was erected in the mausoleum, the one depicting his wife was kept at Windsor until the right moment for its usage came. Since four decades passed between the two deaths, Victoria’s sculpture was lost and added to the mausoleum only months later when it eventually resurfaced.

Read another story from us: The Hilariously Botched Coronation Ceremony of Queen Victoria

Queen Victoria’s body was not disclosed for public viewing, even though the most famous person of the 19th century had just died. The last “friend” the dying monarch demanded to see was her Pomeranian dog, Turi. The royal pet became the last living soul to hear the Queen’s breathing.