In the early 14th century, a nun named Joan of Leeds faked her own death to escape the house of St. Clement by York. She enjoyed an entirely different kind of life after slipping away from the convent. Scholars in the United Kingdom recently translated a letter that the Archbishop of York wrote about the nun’s scheme, which used a “dummy” and a bogus burial.

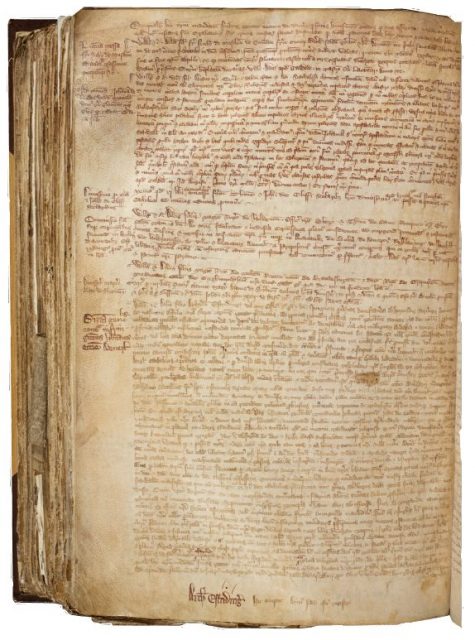

“Her story has been unearthed by researchers at the Borthwick Institute for Archives at the University of York, which are part of a £1 million project to put the 14th century registers of the Archbishops of York online,” according to Church Times.

After her “burial,” Joan was evidently revealed to still be very much alive in the secular world, to the horror of church leaders.

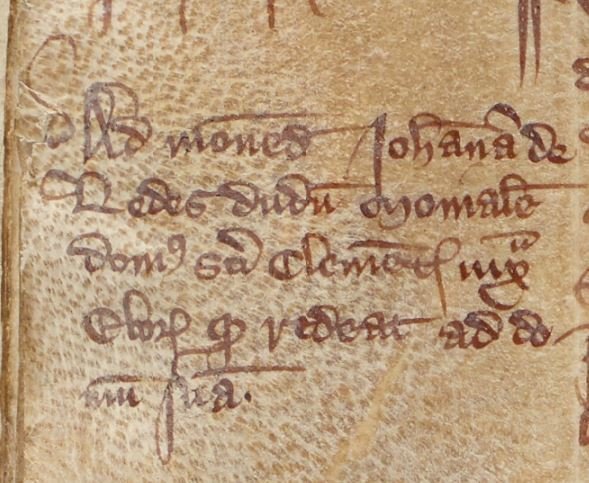

“She now wanders at large to the notorious peril to her soul and to the scandal of all of her order,” the highly disapproving Archbishop of York William Melton wrote about Joan in a record book dated 1318.

The Archbishop continued: “Having faked her death and, in a cunning, nefarious manner, turning her back on the observance of religion that she previously professed, and having turned her back on decency and the good of religion, seduced by indecency, she involved herself irreverently and perverted her path of life arrogantly to the way of carnal lust and away from poverty and obedience.”

University of York historian Sarah Rees Jones, who is leading the digitizing project, told HuffPost that her team isn’t sure if Joan ever returned to the convent ― either willingly or because she was forced.

Presumably fed up with her life as a nun, Joan faked “a bodily illness” and “pretended to be dead.” With the help of some accomplices in the convent, she successfully tricked the heads of her Benedictine convent into thinking she was dead. A lookalike dummy was buried “in a sacred space” among actual dead members of her order.

The letter doesn’t describe what Joan’s dummy looked like or was made of. Sarah Rees Jones has a theory that she may have filled a shroud with dirt or sand and arranged for its burial.

Rees Jones told the Church Times: “There are several cases of ‘runaway’ monks and nuns from various religious houses in the registers. But we don’t always get as much detail as this, and we don’t always have the full story. Women often entered convents in adolescence, and such changes of heart about their vocation were not uncommon.”

While the archbishop said that her goal was a life of “carnal lust,” Joan’s motives are not known for sure.

“This may mean no more (in modern terms) than enjoying the material pleasures of living in the secular world (abandoning her vow of poverty), or it may mean entering into a sexual relationship (abandoning her vow of chastity),” said Rees Jones to Live Science. “We do know that other religious [people] abandoned their vocations either to marry or to take up an inheritance of some kind.”

Cases of runaway nuns were not unknown in the medieval era. Some of them entered convent life in their early teens. History.com reveals that many women had trouble finding decent work to support themselves and faced difficulty finding a husband if their family couldn’t provide a good dowry.

Rees Jones went to say that survival in those days could be hard and one great benefit of living in a religious structure was that you always had bed and board..

Read another story from us: The World’s Oldest Nun who Defied the Nazis and Sheltered Jews

“From archaeology, we can tell that people living in religious houses, even quite small ones like the one that Joan of Leeds lived in, had probably on average a better standard of life than the ordinary run-of-the-mill people outside of the religious life,” she said. The high rate at which women died in childbirth was also a factor in why nuns might typically live a little longer than the average woman.