In the Middle Ages, crusaders from the Latin West left an indelible mark on the cities of the Near East, constructing castles and fortresses that would withstand successive waves of conquest.

Many of these castles still stand today, and in some cases, remain in use. Krak des Chevaliers, perhaps the most iconic crusader castle, was even occupied and used as a military base in the recent Syrian conflict.

However, many of these impressive structures have yet to give up all of their secrets. Even in the late 20th century, crusader structures were still being discovered in the Levant, the most notable of which was the 350 meter (985 feet) “Templar tunnel” running underneath the modern city of Acre. These discoveries continue to shed light on this fascinating period of Middle Eastern history.

The Templars were a military religious order, originally founded to ensure the safety of the regular stream of pilgrims that made the arduous and dangerous journey from Western Europe to the Holy Land.

According to historian Dan Jones, they were so named because their original headquarters stood next to the Temple of the Lord in Jerusalem, and in the 12th and 13th century they played an important role in defining the political and military successes (and failures) of the crusader states in the Levant.

In 1187, however, the city of Jerusalem was lost after a decisive victory by the Ayyubid leader Salah ad-Din (otherwise known as Saladin) at Hattin. The crusader states had lost their capital, and their shock defeat at the hands of a powerful Muslim army launched what would later be known as the Third Crusade.

According to Jones, several large armies set out from England and France to provide aid to the beleaguered crusader kingdoms, with the goal of reconquering Jerusalem.

This was a vain hope, and the armies of the Third Crusade, led (amongst others) by Richard the Lionheart, would eventually leave without reclaiming Jerusalem. However, they did manage to recover the important port city of Acre.

Following a long siege led by the king of Jerusalem, Guy de Lusignan, the Muslim inhabitants of the city surrendered, and Acre became the new capital of the crusader states.

Ever fearful of a renewed attack by Saladin and his successors, the Templars set about constructing an impressive fortress at Acre. The settlement was already well protected by high walls and the surrounding sea, but the new Christian occupants proceeded to construct seemingly impenetrable defenses.

According to Jones, Acre was a strategically significant Mediterranean port, and controlling it was key to controlling access to the rest of the region. However, this meant that it was constantly under threat, both from enemies outside its walls, and from infighting amongst those within.

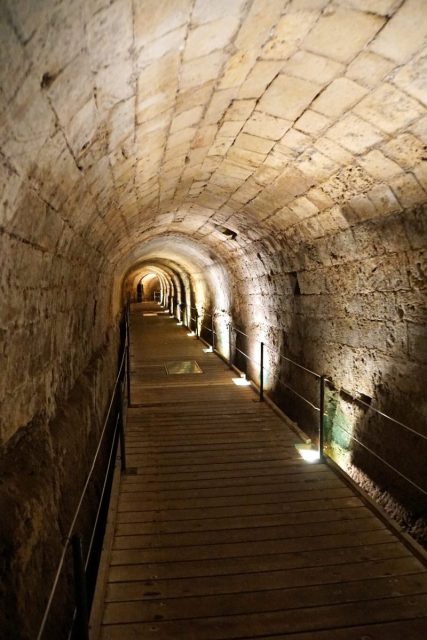

This may explain why the Templars decided to construct a secret underground tunnel, leading from the fortress to the port. This would ensure a quick, easy escape for any inhabitants in case the city was overthrown and could provide a useful, secret channel for supplies if the city was besieged.

However, in 1291, disaster struck. Acre was attacked and taken by the Mamluk ruler of Egypt, Sultan al-Ashraf Khalil, and he ordered that the city be razed to the ground to prevent further Christian reoccupation. This once-pivotal, strategic port fell into insignificance.

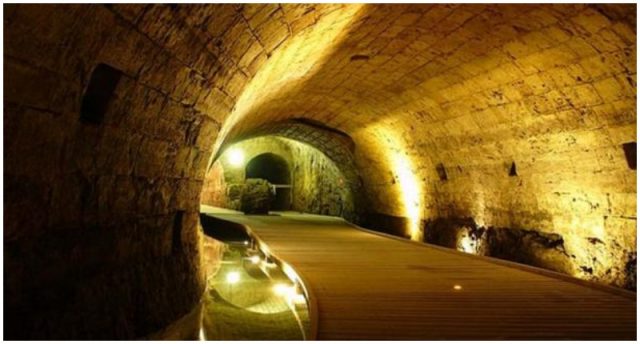

However, in 1994, over 700 years after the fall of the fortress, a startling discovery was made by a woman living in the modern city of Acre. When she sent a local plumber to investigate the cause of her blocked drains, he stumbled into a medieval tunnel running right underneath her house.

Further excavations revealed that the tunnel had been constructed in the Crusader period, and ran all the way from the fortress to the port. This was an extremely significant discovery, as it’s one of the rare pieces of Crusader architecture in Acre to have survived the invasion of the Mamluks.

Today, it’s even possible to visit the tunnel, which has been fully restored, cleaned and drained. Although the Templar fortress may be long gone, modern tourists can still walk in the footsteps of these crusading knights, 700 years after their deaths.