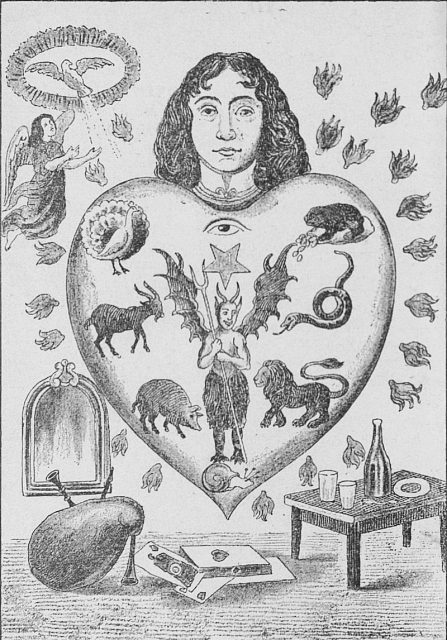

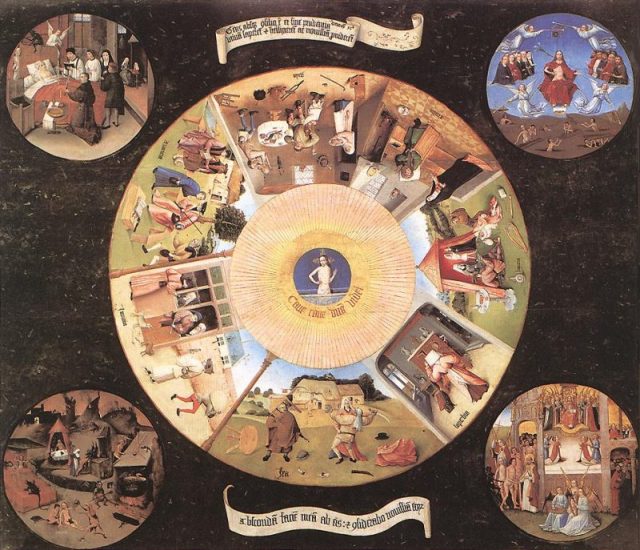

Today’s standard list of deadly sins names lust, gluttony, greed, sloth, wrath, envy, and pride, as opposed to the seven virtues (which are chastity, temperance, charity, diligence, patience, kindness, and humility).

The list rings at least some familiarity even to those who are not religious practitioners at all. The concept of sinfulness, or distinguishing right from wrong, goes way back the timeline. Before even Christianity established itself as one of the world’s major religions.

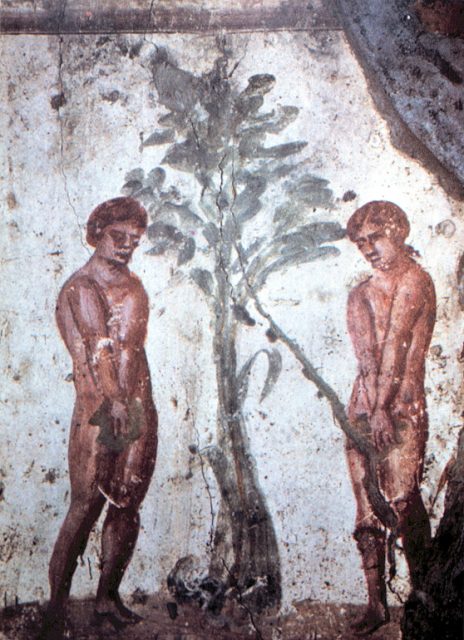

Even before we spoke of the original sin in the Gardens of Heaven, where Adam and Eve infamously devoured the fruit forbidden to them, ancient civilizations already mused on sin.

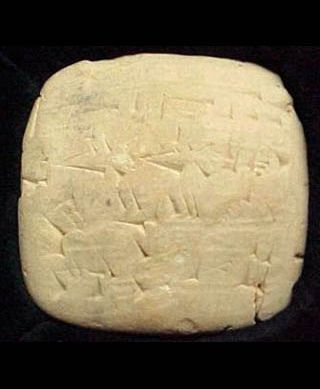

Attesting to that are different relatable inscriptions on the cuneiform tablets left by the ancient Mesopotamian civilizations.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for the prosperous societies that thrived from the 4th through the 1st millennia B.C. within the Tigris-Euphrates river system–its peoples wanted the answers to perennial questions such as why there is suffering in the world, or why some people will succumb to greater life difficulties than others. Great suffering was associated with penalties arranged by the gods in the heavens.

The cuneiform tablets have revealed questions like ‘Has he became close with the wife of his neighbor?’ or ‘Has he broken into the home of his neighbor?’ And also: ‘Has he committed a sin against a god or against a goddess?’

The sentiment is that Sumerians and Akkadians–both which dominated Mesopotamia–were clear on the principles of what’s good and what’s bad behavior, centuries before the completion of the Bible.

Similarly, the people of ancient Egypt as well had a sense of right and wrong. Though, ancient Egyptians carried a sentiment that they can prove their innocence before the gods they obeyed. This was done with the help of correctly uttering the declarations of innocence, among scholars known as “negative confessions.”

Examples of “negative confessions” can be stumbled upon in the Book of the Dead papyri, which document the journey of the deceased into the underworld. ‘I have not committed sin’, ‘I have not worked witchcraft against the king’ or ‘I have not stolen grain’ would be some of the 42 such statements the soul needs to confirm upon facing its judgment day.

Our very own seven deadly sins were more or less pinned down by Pope Gregory I. He had the list refined somewhere at the end of the sixth century A.D., as a means to teach people right from wrong. Such a list cannot be found in the holy scriptures, however, the concept is essentially biblical. A few more names deserve a mention, who attempted to organize lists of sins or virtues before Pope Gregory I.

Within his abundant output of work, the famed Greek philosopher Aristotle authored a list of human merits and virtues. But for each one he wrote stood two easily-identifiable vices. The concept, known as “the golden mean” against Aristotle’s expectations, earned him quite a lot of approval. But the idea about a list still lived on.

During the fourth century A.D., a famous monk of the day attempted to give a more clear list of deadly sins.

His name was Evagrius Ponticus, and as Britannica.com notes, he was “Christian mystic and writer whose development of a theology of contemplative prayer and asceticism laid the groundwork for a tradition of spiritual life in both Eastern and Western churches.” More than that, the philosophy of Ponticus “is sometimes seen as the Christian analog of Zen Buddhism.”

Ponticus saw sinfulness as eight thoughts of evil. He listed them in Greek, and these included: Gastrimargia which stood for gluttony, Porneia for fornication or prostitution, Hyperephania or pride, Akedia or acedia (as understood as the effect of spiritual aloofness), Philargyria or avarice, Kenodoxia or boasting, Orge or wrath, and Lype which denoted sadness over somebody else’s fortunes and well being.

Related Video: Did Jesus Heal his Followers Using Cannabis Oil?

https://youtu.be/cO-UDb6Usq4

From Greek, this concept was eventually translated to Latin by Saint John Cassian, who was a student to Ponticus. Cassian’s translation is how the West became acquainted with the concept of deadly sins.

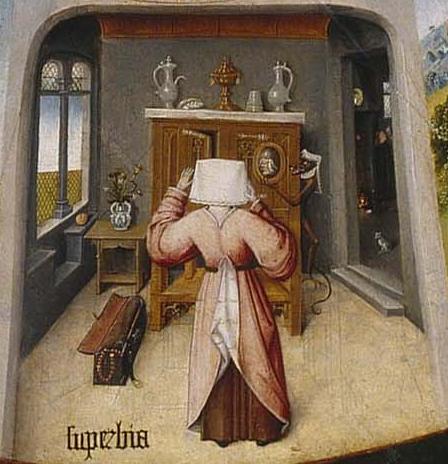

In Latin, the list above read as follows: Gula for gluttony, Luxuria or Fornicatio for lust and fornication, Superbia for pride and hubris, Acedia for sloth, Avaritia for greed, Vanagloria for pride or vainglory, Ira for wrath, and Tristitia for sorrow and despair.

Additionally, these eight sins were subdivided. One group of sins included those relatable to lustfulness such as gluttony and greed. Another referred to anger-fueled wrathful wrongdoings. The third was the sins affecting and spoiling the mind such as excessive pride or sorrow.

Two centuries after Ponticus and Cassian indeed, Pope Gregory I simply had to refine the list of eight evils. At this point, he fused Tristitia and Acedia under one point. The pope also perceived unwarranted boasting as another manifestation of pride, so also fused were Vanagloria and Superbia.

Lastly, the sin of envy–Invidia was added as the list’s seventh deadly sin.

Read another story from us: Biblical Sin City of Sodom Destroyed by Giant Meteor says Archaeologist

The well acclaimed 13th-century theologian Thomas Aquinas would say the sins on Pope Gregory I’s list are the “capital sins.” By then the list had sunk in the teachings of the Catholic Church. Only one alteration had followed, in which sadness was substituted with sloth.