Historically speaking, translating the Bible was not as innocent as one might assume. More than a few cases speak that such an act at some point was deemed heretic by the Church, hence translators were denounced and even put to capital punishment in front of watching crowds.

The first Bible translations appeared out of necessity. The Old Testament, which originally appeared with almost all text in Hebrew, had to be translated to Aramaic in times when Persia ruled over territories that encompassed the east Mediterranean. Aramaic, as opposed to Hebrew or Persian, was the one language understood by everyone in those ancient days. The lingua franca of the region.

Greek translations of the holy scriptures appeared during the 3rd century BC, after extensive, time-consuming translation efforts, and triggered by the fact that Greek was now the dominant language in the then-known world.

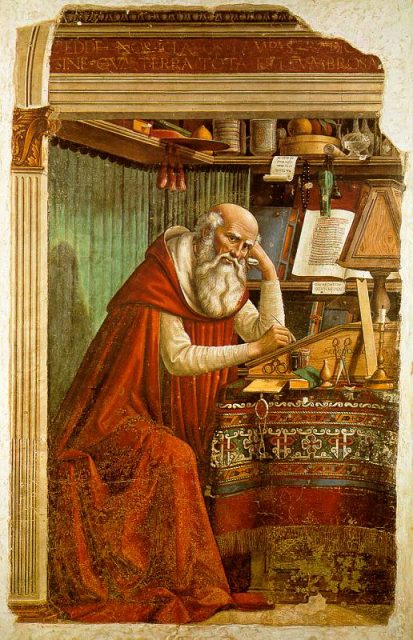

With the further spread of Christianity, the Bible saw its translations into several other languages, such as Ethiopian and Coptic. But the most significant translation was into Latin, following the Roman Empire’s acceptance of Christianity.

The Latin version was ready and set by 405 AD, an accomplishment ascribed to the Bethlehem-born St. Jerome. His version, called the Vulgate, though riddled with mistakes left by copywriters, remained widely accepted in the West for centuries to come.

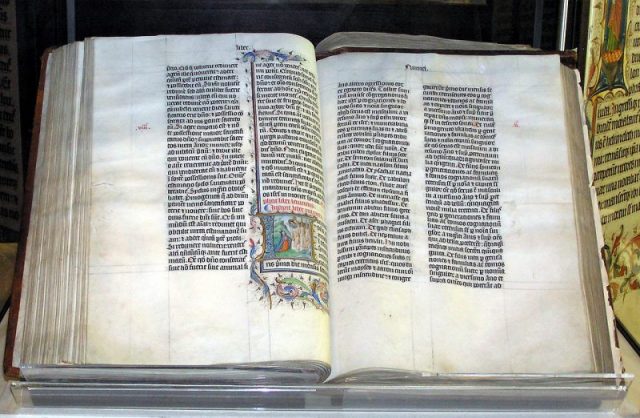

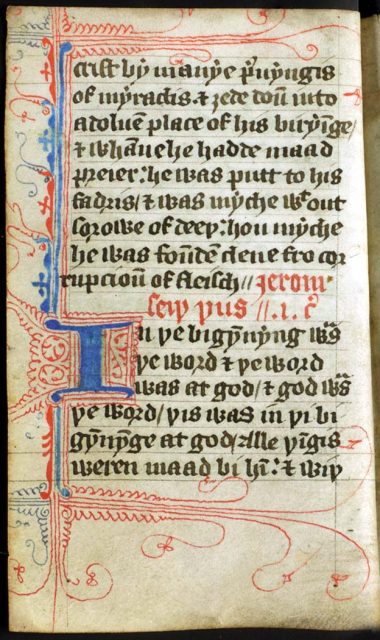

The full, comprehensive translation of the Bible in English did not arrive until the late 14th century. One John Wycliffe is credited for producing the first English version along with his team, but for a while, his work remained accessible only on the black market. With Wycliffe is actually where the history of Bible translations enters a really dark, blood-lustful chapter.

A well-respected, Oxford-affiliated priest and theologian of his day, Wycliffe confronted church officials in his mission to reach out to people of lower scales of society and enable them to read the scriptures for themselves, rather than rely solely on the teachings of clerics.

Things were different in Wycliffe’s days. With striking poverty levels typical for the time period, many people were unable to read or write well. Peasants, for whom learning Latin was a far-fetched reality, could only learn so much about the scriptures by attending church service. Some sections of the Bible were available in English, but that still accounted for a very limited learning experience.

Wycliffe had many career opportunities to ascertain that one of the most vital governing institutions of Middle Age society was greatly corrupted. The doctrines of the Catholic Church were not in favor of the poorer of society.

He would heavily criticize the Church at one point, and would anger the Pope so much that he issued an official document accusing Wycliffe of “vomiting out of the filthy dungeon of his heart most wicked and damnable heresies.” This affected the man, as he lost his job and ended up under arrest.

But what really got on the nerves of the Church was that John Wycliffe was resolute in his plan to complete a full Bible translation into English. That a copy of the book should find its place on the shelves of every home. Since that was against the doctrines of the papacy, the scandal lasted.

John Wycliffe, who died in 1384 before his project was fully completed, would have his bones exhumed and destroyed in 1427, on the orders of Pope Martin. He was regarded as a “disciple of antichrist” and there was no need for anyone to revere his final resting place.

The idea of Bible copies written in languages other than Latin continued to be a thorn in the eye of the church. In 1415, the Czech priest and scholar Jan Hus, an admirer of Wycliffe, was burned alive for producing a Bible translation in his native language. A statue of him still stands in Prague’s main Old Square.

As Harry Freedman tells in The Murderous History of Bible Translation, Hus shared the same sentiment as Wycliffe that real societal change will happen only when people are provided with better means to educate themselves. Such as a fully legible copy of the Bible, written in a language everyone understood. Hus was detained over his actions and faced trial in the Kingdom of Bohemia (the historical predecessor of the Czech Republic).

Hundreds of ministers, archbishops, and even the Pope himself were due to attend his trial, but Hus’ remorseless and cold-blooded execution soon triggered a fierce counter-movement.

Admirers of Hus, mostly the Czech-speaking population of the Kingdom of Bohemia, would group themselves in military factions and confront and defeat several crusades sent by the Vatican and its allies in between 1419 and 1434. These confrontations became known as the Hussite Wars.

Calamities related to Bible translations did not end here. Things got even more vigorous by the 16th century when death was sometimes meted out for the most mundane of cases. Such as translating a single prayer from Latin to English.

Wycliffe’s Bible remained blacklisted in England, where it was illegal to possess a copy of it, if one only had the fortunes to obtain it in the first place. That means that people still had scarce knowledge of the scriptures, until another scholar and high-profile translator tried to give another attempt. His name was William Tyndale.

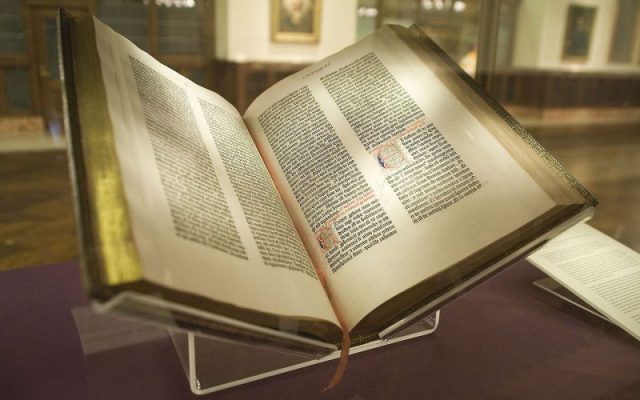

Educated at Oxford and working at Cambridge, Tyndale was unsurprisingly denied permission by the Church to work on a Bible translation from Latin into English. He sought better luck in Germany and by the summer of 1525 his take on the New Testament was ready to be shipped to England. The invention of the printing press allowed for faster production of copies.

Even though Tyndale was working from outside England, he was still in an extremely dangerous business. He was always on the run, changing locations to remain safe from secret agents until he was betrayed in Antwerp. Like his colleagues detained over the same wrongdoing, Tyndale too received a death sentence. He was burned at the stake in 1536, near Brussels. A similar fate followed dozens caught owning a copy of his Bible or trying to sneak one into Britain.

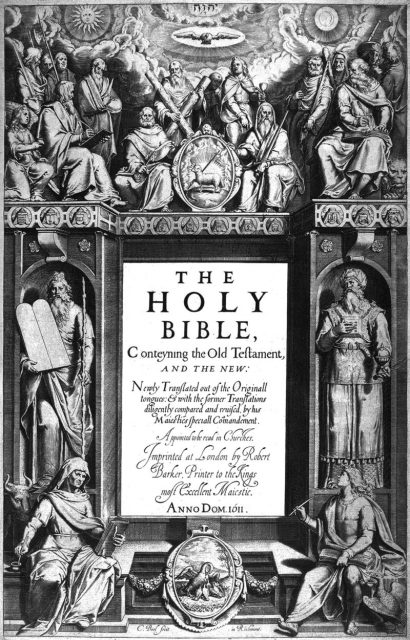

Britannica.com further notes: “At the time of his death, several thousand copies of his New Testament had been printed; however, only one intact copy remains today at London’s British Library. The first vernacular English text of any part of the Bible to be so published, Tyndale’s version became the basis for most subsequent English translations, beginning with the King James Version of 1611.”

Read another story from us: Artificial Intelligence is Deciphering the World’s Oldest Writings

It took a little longer until the church accepted that any person is free to study and interpret the Bible on their own. To this date, the Bible remains the one most translated book on planet Earth.