The North Malukus are a chain of islands that form the larger archipelago of Indonesia. Home to the heavenly retreat of Bali and otherworldly Javanese coffee, Indonesia boasts more than just human indulgences.

The northern islands are not nearly as big as their southern compatriots that boast supreme comfort and morning energy, but they do hold a very important treasure of the biological world.

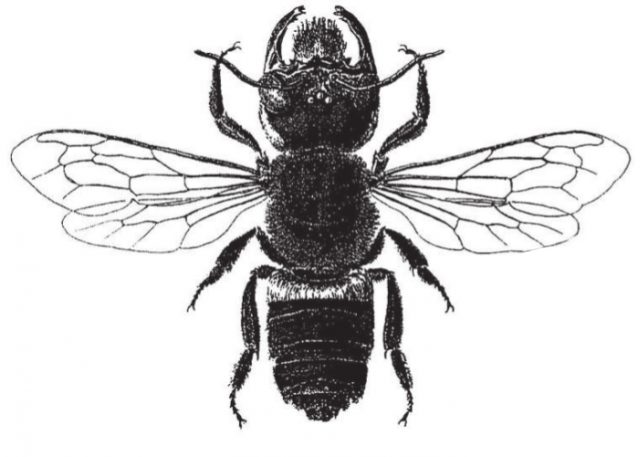

On the islands of Tidore, Bacan, and Halmahera lives the world’s largest species of bee. At least, it’s supposed to. Growing up to the length of the average adult’s thumb, with a wingspan of 2.5 inches, Megachile pluto is more colloquially known as the Giant Bee.

Also officially name Wallace’s Giant Bee, Megachile pluto gets its name from the naturalist who, in 1858, first discovered the insect: Alfred Russel Wallace.

Wallace is a scientist of note, though his name may have gotten a bit lost in history. Most people will have heard of his partner with whom he co-developed a very important theory: Charles Darwin.

Though Wallace first discovered the bee, he didn’t give it too much limelight. It wasn’t until over 100 years later, in 1981, that an American entomologist confirmed its existence, seeing for himself about six different nests on these very same northern Indonesian islands.

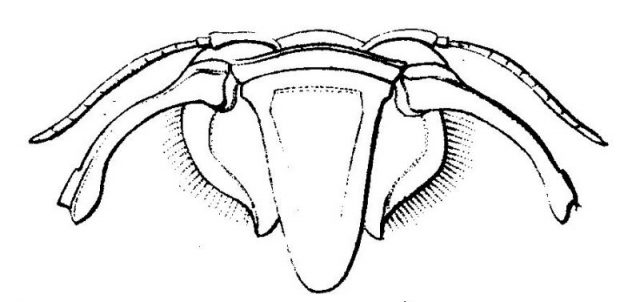

Megachile pluto’s nests are communal. She builds them inside preexisting termite tree mounds, employing sticky tree resin to defend her nest against the invasive termites.

These unlikely neighbors are a key choice for Wallace’s Giant Bee, as the termite mounds help protect the nest from predators. Even local residents are unaware of these nests, they’re so well hidden.

Just this month, however, a new team of entomologist Eli Wyman and wildlife photographer Clay Bolt confirmed the bee’s existence once again after a 38 year silence. Sponsored by Global Wildlife Conservation, the duo participated in the group’s “hunt for lost species” and managed to momentarily catch a Wallace’s Giant Bee, film and photograph her, before setting her loose again. It’s the only footage of a live Megachile pluto.

Just last year, Wyman contributed to an article for National Geographic’s blog after two significant events. After a trip to New York, where at the American Museum of Natural History he was able to examine the only existing specimen of Megachile pluto up close, Wyman became interested in this legendary insect.

It then transpired that two (not one, but TWO!) specimens of Wallace’s Giant Bee unexpectedly went up for auction on eBay in April, 2018 — a significant resurgence before this year’s rediscovery. This pushed Wyman to make his February 2019 trip to Indonesia.

Wallace’s Giant Bee is in danger and further scientific studies of it could help keep it buzzing. Right now, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) does not restrict international trade even though the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) labels Megachile pluto as a Vulnerable species.

This meant that the $9,000 online sale of each of the Wallace’s Giant Bees was completely legal. This greedy, collectible mind set, mixed with a large growth of palm oil plantations on the islands concerned, puts Megachile pluto at great risk.

Clay Bolt points out that he and Wyman “weren’t sure [it] existed anymore,” making their find all the more momentous.

The pair, along with IUCN and other invested conservationists, are hoping to change the Wallace’s Giant Bee’s future, securing it the protection it needs to survive.

Though it’s not confirmed whether or not Megachile pluto creates a giant amount of honey, it has certainly made a giant stir in the insect community this week.