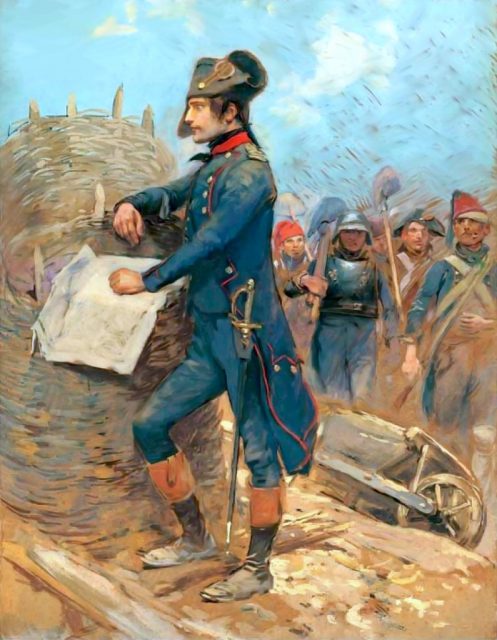

After having conquered most of Europe, Napoleon suffered defeat and gave up his throne in 1814. A few months later, he escaped from the island of Elba and returned to the French mainland, rallying men as he went and forming a new army. The unloved and unpopular Bourbon king of France fled to Belgium, and Napoleon Bonaparte became Emperor once again, soon raising an army 200,000 strong.

His former enemies, England, Prussia, Russia, and Austria, did not sit idly by while Napoleon reclaimed his throne. They raised new armies and formed the so-called Seventh Coalition against him. Inflicting defeat on the Prussians and many casualties on the British, Napoleon hoped for one final decisive battle that would allow him time to secure his place in France.

Of course, this was not to happen. Bonaparte met the British armies under Wellington and the Prussian armies of Blücher at Waterloo in Belgium and suffered the final defeat of his military career.

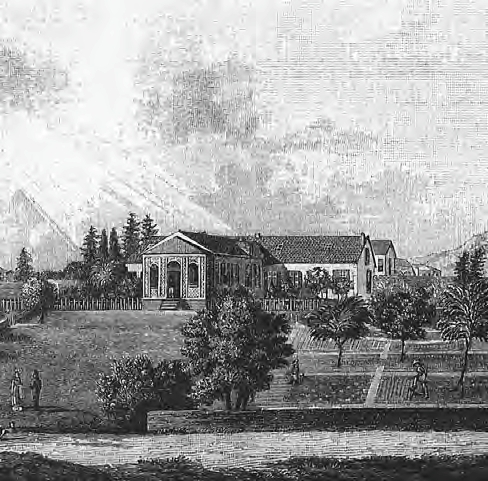

Once again, the victorious powers sent him into exile. Not wishing to make a martyr of him in France, they sent him to the distant British-held island of St. Helena.

One would be hard-pressed to find a more isolated place on the planet than St. Helena. Located almost halfway between South America and Africa in the Atlantic, the island is over 1,600 miles from any other significant land – which would be Angola in Africa.

This time, the British meant for Napoleon to stay in exile. They even posted guards on the even more remote island of Tristan de Cunha, the closest land and over 1,200 miles away, in case the Frenchman escaped and wanted to use it as a staging area.

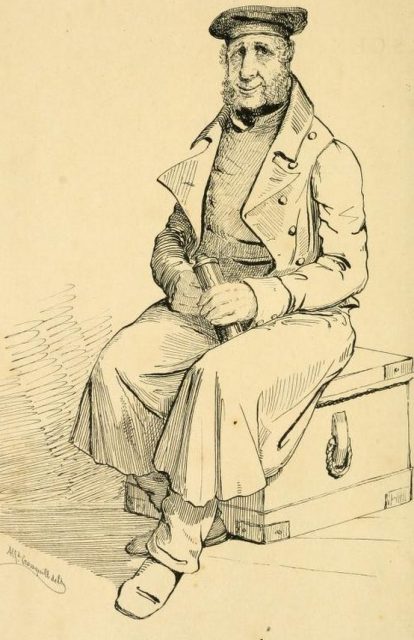

Enter Tom Johnson (sometimes referred to as Thomas Johnstone), one of the most infamous British criminals of the time. Johnson had led a life of crime since he was 12 years old and had even escaped from prison twice.

He made a living by smuggling goods in an out of Europe in violation of several bans from both England and France. Despite his criminal history, the British did employ him on at least two commando-style expeditions into enemy-held territory, though he did con the famed British author Sir Walter Scott about having piloted Admiral Nelson’s ship during one of his battles.

But these adventures may not have been the most exciting chapters in Johnson’s life. In his older years, he claimed to have been offered 20,000 British pounds to effect a rescue of the ex-emperor — using a submarine, a technology that was not even close to successful development, or was it?

In 1835, a book entitled Scenes and Stories of a Clergyman in Debt was published, relating the authors’ experiences in debtors prison. One of the men he met was Johnson, who relayed the tale of his part in a plot to free Napoleon from St. Helena. In the book, the author (which some believe to be Johnson himself) describes in detail one of the submarines supposedly built to free the French emperor.

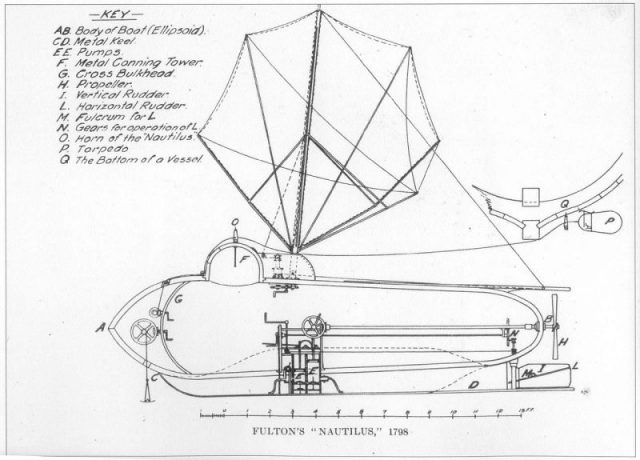

The sub was to carry 20 “torpedoes” in case the English sent a fleet after them (early subs’ weapons were waterproof barrels of gunpowder rigged to explode with a timed spark). It was 40 feet long, 10 feet wide and weighed 23 tons.

All in all, the description closely matches what was later built in Holland and the United States in the 1860s. Accompanying the large submarine, dubbed the “ Eagle”, was a smaller sub, the “Etna”.

Related Video:

https://youtu.be/MqllihZqzf4

Nowhere in the book does the author say how the sub was to get to St. Helena (though he did describe the sub having sails) but when it did arrive, it was to let loose a woven net of corks to cushion the smaller sub from pounding against the rocks of the island.

Next, Johnson and his men were to carry a “mechanical chair”, 2,500 feet of rope, and set up a pulley system at the top which would allow “His Imperial Highness” to be lowered to the waiting submarine below.

Napoleon would be whisked from his house in the disguise of one of his servants. Apparently, Johnson had contacts on the island (or so he said) who described the guards, their habits and the field of view from various points near Napoleon’s house.

The 19th century commando team would then transfer to the Eagle and effect a getaway, hopefully sinking any British ship that might happen upon them.

Unbelievable, right? Well, the Marquis de Montholon, a general who voluntarily went into exile with Napoleon, later published a book about his time on St. Helena long after the death of Bonaparte in 1821. In it, he wrote about a plot to get Napoleon off the island with a submarine that they had paid some 6,000 gold pieces for (worth $1 million today).

In 1833, the official British naval journal The Naval Chronicle also describes Johnson in connection with a submarine plot – and this was published before Scenes and Stories.

Ten years before both, a publication entitled Historical Gallery of Criminal Portraitures told the story of how and why Johnson felt himself able to build a submarine: he had worked with the American Robert Fulton, who, during the Napoleonic Wars, had come to England to sell the Royal Navy plans for a submarine – after first building a working prototype of a submarine for Napoleon, which Fulton had sailed on the Seine River in Paris.

When the French showed no interest in a larger second prototype, Fulton went to England to see if they would buy his idea. Now the capper: documents found in British archives show that Johnson had worked for the British Navy in 1812. During the conflict, Robert Fulton was actively trying to build a submarine for the U.S. Navy.

Johnson’s documents show that he was “on His Majesty’s Secret Service on submarine, and other useful experiments…”, and that he had drawn rough plans of a submarine matching his later description.

It says nothing of the main problems everyone working on the boats faced: how to get underwater, stay there, and make sure it could re-surface. Two very dangerous test runs in the Thames are described in other official papers.

Johnson wanted £100,000 for his sub. Another report at the time indicates that a Sir George Cockburn, noted for burning the White House to the ground in the War of 1812, inspected a submarine in 1820 to assess its cost and offered Johnson much less for it. This is the same time that French officers were offering Johnson the equivalent of $1 million.

Assuming there was a plot involving a submarine, a mechanical chair and a costume, it came to naught – Napoleon refused to entertain any escape attempt that included him disguising himself in any way.

Read another story from us: The Bizarre Journey of Napoleon Bonaparte’s Penis

If he escaped, he would do it “with his hat on his head and his sword at his side,” as one of his aides later put it. The former Emperor of France died on St. Helena in 1821. Johnson apparently left debtors prison and obtained a significant pension from the Royal Navy, allowing him a comfortable retirement.