Imagine you are attending a soirée at a local château. Now imagine that into the room walks a lion, only it is not a real lion; it is animatronic. Now imagine that it is the early 16th century. This would be surprising to anyone, but perhaps less so if you were in the company of a certain Leonardo da Vinci.

Born in Italy as Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci in 1452, da Vinci’s name has become synonymous with invention, engineering, architecture, science, mathematics, astronomy, cartography, and, of course, art.

The painter of the Mona Lisa, da Vinci is known to have created numerous other masterpieces throughout his 67 years, including The Virgin and Child with St. Anne in 1510, The Virgin on the Rocks in 1486, and The Last Supper in the 1490s.

Considered to be a “universal genius”, the scope of da Vinci’s interests were unprecedented. According to art historian Helen Gardner, whose 1926 book Art Through the Ages is still the standard text for American art history classes, da Vinci’s “mind and personality [were] superhuman, while the man himself mysterious and remote.”

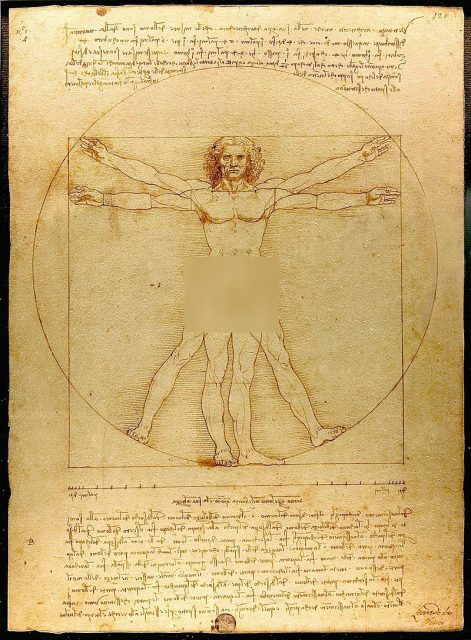

Although known primarily as a painter, da Vinci’s mind was equally scientific. His drawing of The Vitruvian Man is thought of as a cultural icon and has been reproduced a myriad of times on everything from tote bags and postcards to the Euro.

Da Vinci dissected 30 cadavers in his lifetime by his own count, creating intricate and highly detailed drawings of both animal and human anatomy. While he never considered himself a medical professional and did not teach anatomy or publish his findings, his drawings have served as the basic principles of modern scientific illustration. But it was his ingenuity with regards to technology that really set him apart from his contemporaries.

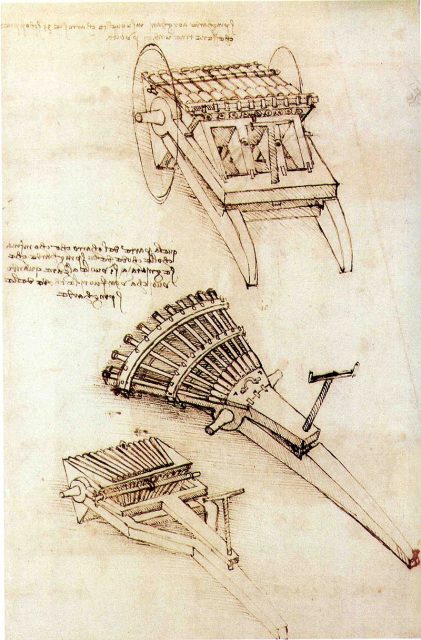

In his life, da Vinci conceptualized a wide variety of machines and mechanisms, many of which we take completely for granted today. In addition to a type of helicopter, da Vinci drew up plans for a winged flying machine, a double-hulled ship, solar power, an armoured fighting vehicle that resembles an early tank, an anemometer, which measures wind speed, parachutes, scuba gear, a car, a revolving bridge, and a robotic lion.

In 1517, about a year after he took up residence at Clos Lucé, da Vinci was commissioned to create an automaton for the king, François I. Da Vinci moved to Amboise in 1516 at the request of the king, to be a court painter, architect (he is believed to have contributed significantly to the design of François’ estate at Chambord) philosopher and engineer. Paid 700 gold crowns a year and given the château as his home, he was ordered to “think, work, and dream.”

Da Vinci appears to have created three different animatronic lions in his lifetime. The first was in 1509, which was designed for the grand entry of Louis XII into Milan. While it could not walk, it could rear on its hind legs to present a lily – a symbol of France.

The second lion, created in 1515, could walk and move its head and was presented to François I when he visited Lyon. When the king tapped the lion with his sword, a compartment opened to reveal a lily.

The king was so impressed by this that he invited da Vinci to his court. The artist agreed, arriving by mule and bringing with him many of his paintings, including one of a woman by the name of Lisa Gherardini – the Mona Lisa. It has remained in France ever since.

Da Vinci’s original lion has long since been lost to time, and no drawings or plans exist, despite the plethora of notebooks that da Vinci left behind. Carlo Pedretti, a da Vinci scholar, wrote: “The irony of the whole thing is that there is not a single hint in Leonardo’s manuscripts of this (which may be his) greatest technological invention… Imagine having a lion walk. This is top technology!”

Related Video:

https://youtu.be/dtCairKbsL8

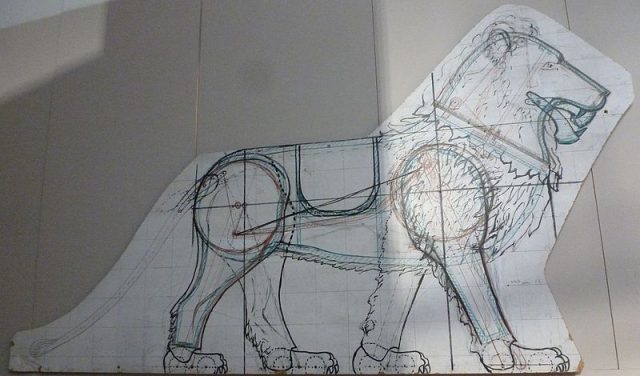

However, in 2009, another mechanically-inclined individual named Renato Boaretto used a description of the third lion as inspiration and created his own version: “My big problem was to try to get inside Leonardo’s mind and to try to think as he might have thought, based on the technology which existed or that he envisaged in his sketches for other machines.”

Like da Vinci, Boaretto had been commissioned by another François — François Saint-Bris, president of the Château Clos Lucé and surrounding park. Saint-Bris had plans to turn the park into a cultural area, devoted to both da Vinci as well as his renaissance contemporaries such as Shakespeare and Machiavelli.

But building the lion was not a simple task. According to Boaretto, “Leonardo’s big problem was to give such a heavy machine – 50 or 60 kilos – enough power in one motor in a limited space to walk forward and to move its head and tail.” All of this had to be done using technology that would have been contemporary to da Vinci.

In order to solve this problem, Boaretto used a complex entanglement of pulleys, chains, wheels, gears, axels, and pendulums. The lion can be wound up using a crank, or key, and the handyman of the Clos Lucé is often called upon to turn the crank whenever visitors to the château want to see the lion move.

Like the original, it can walk, shuffling forward about 10 steps, as well as move its tail, open its mouth, and rotate its head. And, true to the design of its predecessor, it also has a secret compartment for a fleur-de-lis.

In addition to the new lion, four original sketches by da Vinci were put on display at the Clos Lucé as part of the permanent exhibition Leonardo da Vinci and France. It was the first time the sketches, which were housed in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, were returned to the place where they were created.

Read another story from us: The Futuristic Weapon Designs of Leonardo Da Vinci

Boaretto’s lion, as well as numerous other replicas of da Vinci’s creations, can be seen today at the Château Clos Lucé, in Amboise, France. Da Vinci lived here for the last three years of his life and died in his bedroom in 1519. The chateau has been restored as a museum devoted to this true Renaissance man, his life and his incredible talents.

Correction: In the original version of the article we misstated his year of birth of as 1542. The correct year is 1452. We made the correction on 4/8/2019.