When faced with imminent war, people make choices that they might not otherwise make as their thoughts turn to how best to preserve as many lives as possible.

That’s how it is that, during the 1950s, some states started programs to tattoo children’s blood types onto the left side of their torsos, according to Mental Floss, effectively turning the tots into walking transfusion resources.

The program was called Operation Tat-type, and was implemented some states with the goal of making it easier to give transfusions after an atomic attack.

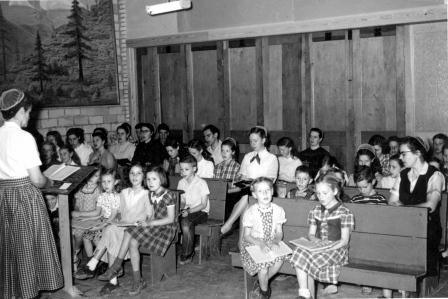

The tattoos could act as a fast way of finding an immediate source of blood for transfusing into the critically injured. To today’s eyes, it seems impossibly awful to put a child in that position, but, in the first few years of the 1950s, as the US was entering the Korean War and the Cold War was at its height, some officials viewed it with a much fonder eye. Children and adults alike lined up to do their part and get themselves typed and tattooed.

The idea was brought to the US by an AMA physician, Andrew Ivy. While he was testifying at the Nuremberg trials after World War II, he observed that some Nazi SS members had their blood type tattooed on their bodies.

When Ivy got back to Chicago, he brought the idea with him as a way of dealing with the rapidly dwindling blood supply that was a side effect of the Korean War.

That way, if the Soviet Union decided to start attacking targets in the US, there would be a ready blood supply to help treat those who were suffering from the radiation sickness that follows a nuclear attack.

Ivy was part of the Chicago Medical Defense Committee, and he lobbied for the idea to be implemented in Chicago. The Chicago Medical Society, the Board of Health, and even some citizens were in full support of the program, although they never ended up launching it in that city.

One letter to the editor of a newspaper in New Jersey even suggested tattooing people’s social security numbers onto their bodies to make identification easier, should the need arise. Happily, there’s no evidence to suggest that the idea ever went farther than the letter it was written in.

Although willing, that didn’t mean the kids were excited about it, though. A columnist for the Washington Post related an account from John MacGowan, who was in first grade at Lanier school in 1952, in Munster, Indiana, and was one of the children who was tat-typed.

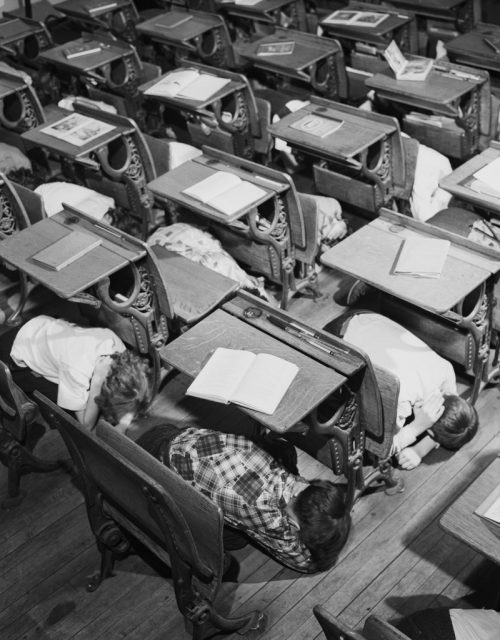

MacGowan described the process as “horrific”, with his class being led up a hallway to the health room where the tattooing process was being done. As they stood in line to wait their turn, the children would see the others enter the room one at a time.

The buzzing of the needle gun would be followed by the scream and/or crying of the child being tattooed. MacGowan said that every child still waiting in line would go a little paler as each victim walked past them.

He also joked that the highest grade he ever got in school was the A+ tattooed on his torso – his blood type.

The youngest child to have had the tattoo is believed to be Paul Bailey of Milford, Utah, who was born at Beaver County Hospital in 1955. He was given his tattoo only about two hours after his birth. A hospital employee made sure to point out that they had received parental consent beforehand.

Despite the potential religious objections to tattoos among the Mormon population in Utah, a representative of the Church declared the tattoos exempt from the prohibition against members of the church defacing their bodies, which increased willingness to participate in the program among some Utah residents.

Related Video: 70 Years of Air Power – Korean War

https://youtu.be/JJu3DZmp8ZY

Despite the efforts being made in Utah and Indiana to advocate for and spread Operation Tat-type, the idea never expanded past those state’s borders. By the mid to late ‘50s, enthusiasm for the idea was dying down.

Not only did the conclusion of the Korean War reduce the strain on blood banks, but also the public was coming to understand that the real threat of nuclear attack was of a scope that rendered such measures largely pointless.

There are still plenty of people around today, though, that bear the stretched, pale reminders of that piece of our history inked onto their skins.