The early years of the 20th century were ripe with a feeling of possibility. Science and technology were booming, explorers were charting new paths into undiscovered territory, and anything – everything – seemed within the grasp of those who were daring enough to try.

It was that wild sense of adventure that resulted in a road trip that remains remarkable, even today. It all began with an article in French newspaper Le Matin, according to History Today. In January 1907, the paper declared that a man with an automobile could go anywhere.

It followed that pronouncement by asking if there was anyone who would be willing to prove it by driving from Peking (now Beijing), China to Paris, France in the coming summer.

The notion wasn’t meant to begin a race, only to make a point about the level of access one could have if they owned a car, but the idea fired people’s imaginations, and, at the outset, there were 40 entrants ready to take on the challenge.

When the time came, however, only five teams sent cars to China. Italian team Prince Scipione Borghese and Ettore Guizzardi took along an Itala; Charles Goddard and Jean du Taillis arrived in a Dutch-built Spyker; Auguste Pons drove a small 6HP Contal Cyclecar; and Frenchmen Victor Collignon and Georges Cormier both turned out with De Dion-Bouton tricycles. Each car would be accompanied by a journalist who would document their trip, sending out stories along the way.

According to Skoda Motorsport, the participants came from pretty diverse backgrounds and levels of ability. Prince Borghese had a top-of-the-line vehicle with the most powerful engine, at 40HP.

He planned out spots to have spare parts and fuel stocked along the route — while, at the other end, Charles Goddard borrowed a car for the event and bargained for his ticket to China by playing piano for the first-class passengers on his ship. He made it as far as Berlin by begging and borrowing to get money for fuel, but his race ended there when he was arrested on suspicion of fraud.

The route was harrowing. There weren’t any roads for much of it, let alone gas stations, so they ended up carting fuel out along the route by camel to the autos. The course was 9,317 miles, going across Mongolia, the Gobi Desert, and Siberia before making its way south across Europe to Paris.

There were no detailed maps — the cars would follow a telegraph route that would both provide direction and allow the journalists to send out their stories. The first of the drivers to reach Paris would receive a magnum of Mumm champagne, as well as glory and bragging rights.

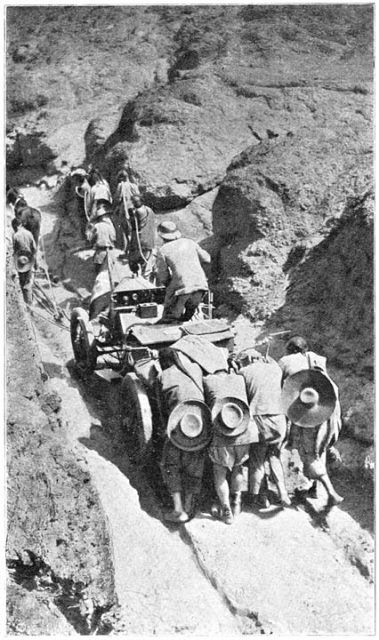

The first real obstacle for the cars would be navigating the mountains of Mongolia, along narrow trails surrounded by dangerously steep cliffs. Most of the cars involved lacked the power to navigate the terrain on their own and had to be pushed up some of the inclines or pulled by animals.

It wasn’t until they reached the Gobi desert that the first driver had to drop out of the race. Auguste Pons ran out of fuel and had to hike through the desert to return to civilization, nearly dying of thirst before nomads found and rescued him.

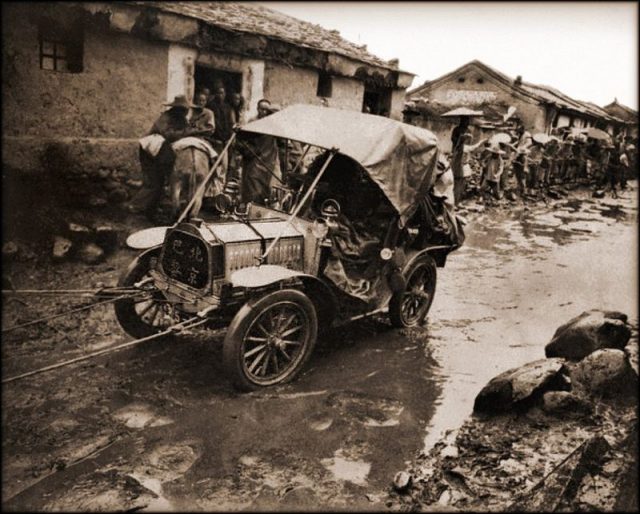

The little Cyclecar he was driving was left where it died. The other four teams made it through the desert, often using their own drinking water to keep their engines going in the extreme heat.

Leaving the desert for the Siberian forests posed a different challenge. The drivers were supposed to be following a military road, but when they arrived they discovered that the road had long been abandoned and overgrown, and its bridges were either in disrepair or entirely gone.

Related Video: Chevrolet Car Range (1960)

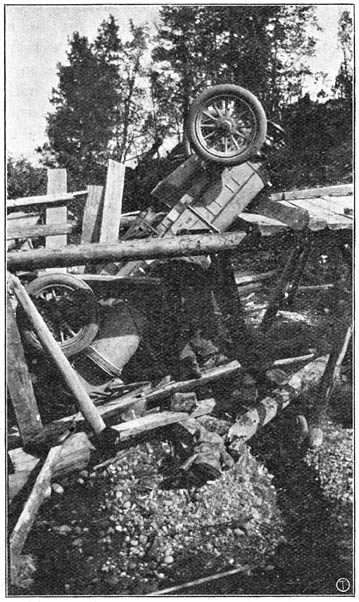

Borghese’s Itala was many hours ahead of the remaining racers, which proved to be lucky as his vehicle had its challenges in Siberia, falling through a bridge and landing in a ravine at one point, nearly being hit by a train while it was stuck on the tracks at another.

He suffered damage to his car’s wheels from dealing with mud and had to have a local cartwright make him a replacement. Even after all of that, though, his lead was still large enough that when he was in Russia he could make a detour to St. Petersburg for a party.

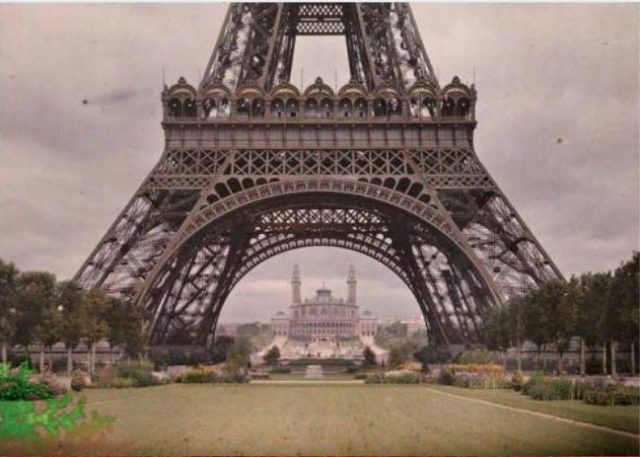

Once Borghese’s team hit Europe, the rest of the trip went as smoothly as such a trip could, at the time. He won the race, rolling into Paris on August 10th — two months from the day he left Beijing. The three remaining teams didn’t arrive in Paris for nearly another three weeks, with Goddard’s Spyker being driven by a replacement driver at the finish.

The race was an astonishing event at a time when motorsports were so very new. The epic trek wasn’t repeated for decades given the difficulties brought about by the world wars and Cold War, but it was finally revived in the 1990s.

Read another story from us: The car where Bonnie and Clyde met their end was raced in the 80s

The race was recreated as a rally for vintage cars and has been held six or seven times since then. It will be run again in 2019, with drivers of vintage cars taking to the trek in the same spirit of adventure that prompted the very first race.