Nothing says space travel quite like a clock counting down to blast off. Add a loud voice commentating on the action and the listener is transported to a scenario depicted in dozens of movies.

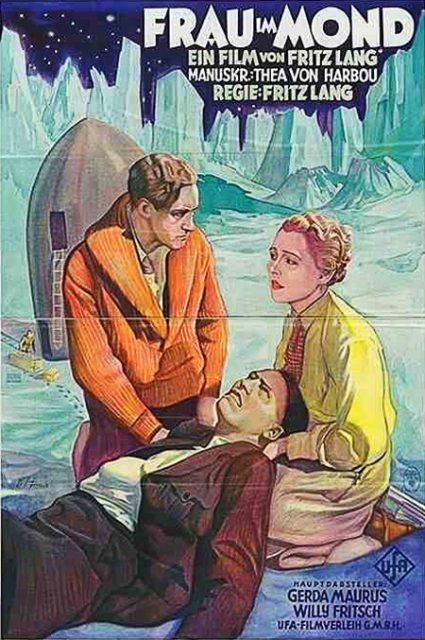

Ironically that dramatic image of a rocket countdown actually comes from a motion picture. Specifically Frau im Mond, or Woman in the Moon, a silent film directed by the legendary Fritz Lang in 1929.

It was Lang, co-creator of sci-fi classic Metropolis, who impacted the real life world of science and engineering… though he had some help. Metropolis had been released two years earlier and the expensive production hadn’t received a rapturous reception. For his next project, Lang decided to leave the city and head toward the stars.

Woman in the Moon was based on a novel by Thea von Harbou — Lang’s wife, who had also written Metropolis. A 2014 Guardian review of the movie version called it “Less ambitious and mystical” than its predecessor. However the thrill-packed story “combines an imaginative adventure yarn, a triangular love story and a conspiracy thriller.”

Entrepreneur Helius (played by Willy Fritsch) wants to take a rocket to the moon, believing he can find gold there. While this sounds far-fetched, it is in fact an idea suggested by Prof. Mannfeldt (Klaus Pohl).

Helius’ assistant Friede (Gerda Maurus) joins the crew, which is just as well as the craft is named after her. She is described as “the modern liberated woman both men love”. The other man being Windegger, another assistant to Helius.

A team of greedy businessmen blackmail Helius into taking their rep Turner (Fritz Rasp) aboard, leading to conflict and intrigue once the existence of lunar gold is revealed.

With a running time of nearly three hours, there’s certainly room to pack a lot in. Many regard the finished product as a landmark in science fiction cinema. The reason for this lies in Lang’s attention to detail.

Despite the far-fetched premise of treasure on the Moon, when it came to rocketry Woman in the Moon was surprisingly accurate. In fact it influenced aspects of space travel in various ways.

Motherboard pointed out the movie’s innovative features in a 2017 article, saying it “was far ahead of its time and anticipated a number of developments in rocket science, including the countdown to launch sequence.”

Intertitles took the place of sound in silent film, with Lang showing the numbers of the countdown getting bigger and bigger to really build the tension. Woman in the Moon also presents ahead-of-their-time ideas like “launching the rocket from a pool of water (launch pads are normally wet today to dissipate the heat), and the use of a multistage rocket to reach the moon.”

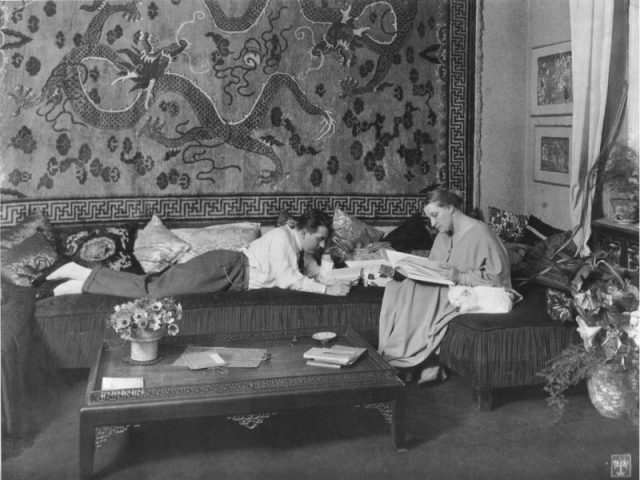

Aside from Lang and von Harbou the main trail-blazer behind the future-predicting endeavor was an Austro-Hungarian named Hermann Oberth, who worked as the film’s scientific advisor. A physicist and engineer, Oberth was inspired by Jules Verne. In 1923 he wrote Die Rakete zu den Palnetenräumen (By Rocket into Planetary Space).

This pamphlet sought to shine a scientific light on the concept of journeying into the cosmos. Space.com wrote in 2013 that among other things it “not only mathematically demonstrated the ability of a rocket to leave Earth’s orbit, but also explored the theory that rockets could operate in a vacuum, where they could travel faster than their own exhaust.”

The work started life as a dissertation, though was rejected on the grounds of being too fanciful. Eventually it became a book and surprise hit. Post World War I society was excited by the prospect of leaving a drab and dreary Earth behind, and Lang was only too eager to put their fantasies on screen.

The character of Prof. Mannerfeldt was mocked for his ideas, a feeling Oberth and contemporaries such as Robert Goddard were used to. Still, he had the last laugh. The pioneer who had his dissertation dismissed went on to greatness.

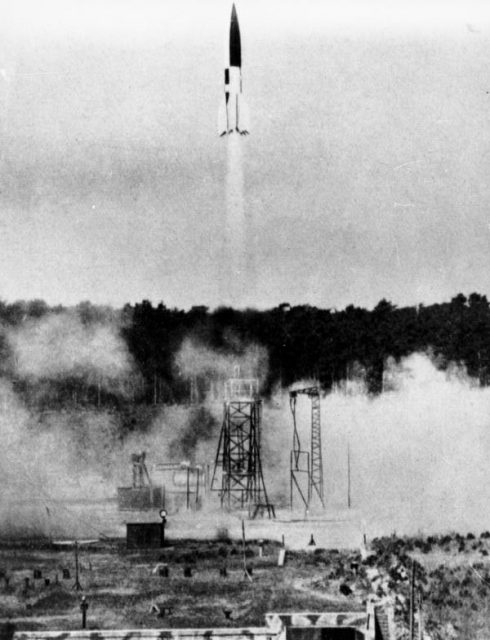

Lang moved to Hollywood, whereas Oberth worked in Germany alongside “space architect” Wernher von Braun (who Oberth had previously taught) on the V-2 rocket. Interestingly, the Nazis stopped showings of Woman in the Moon in case it blew the lid on their plans.

Read another story from us: How Rasputin Initiated the ‘All Persons Fictitious’ Disclaimer in Movies

He eventually moved to the U.S. so he could work on the Saturn V rocket, something closer to his Verne-infused origins. Though his field of expertise was the practical, he used science-fiction as a springboard into the utterly destructive and also truly wondrous sphere of rocketry.