It may surprise you to learn that a thriving business exists to convey tourists to Chernobyl, the site of the catastrophic 1986 nuclear reactor meltdown in Ukraine.

More than 30 people died within days of acute radiation, about 4,000 died later of related cancers, and experts say the surrounding area won’t be fit for human habitation for 20,000 years.

Nonetheless, in the year 2019 a great many people seem eager to set foot in the contaminated area. Its full name is the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Zone of Alienation, which morphed into The Exclusion Zone, and finally…The Zone. Lately however people have even begun to attempt to live in the Exclusion Zone, returning to where they once lived. Check out the video on this:

https://youtu.be/tbNeYNLrWwA

It may appall you to discover that the motivation for a considerable number of Chernobyl tourists is to see how closely The Zone matches the scenes in their favorite video game. S.T.A.L.K.E.R., Shadow of Chernobyl which has sold 2 million copies worldwide. And there are others.

But most of all, it may intrigue you to discover that the partially destroyed Chernobyl nuclear plant and the abandoned town of Pripyat that once housed its workers are not necessarily what visitors are most drawn to once they enter The Zone.

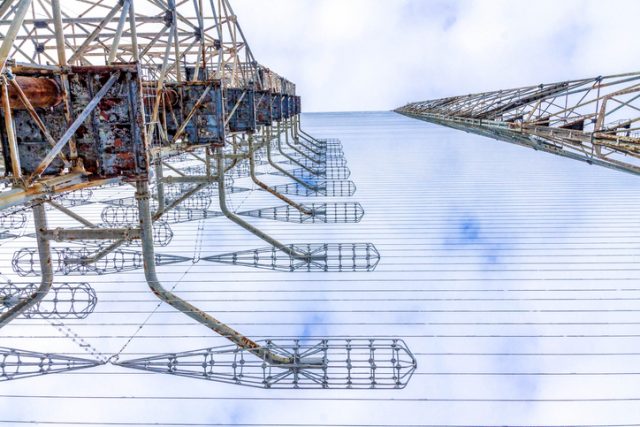

Instead, they are fascinated by something rising out of the forest a short distance away: the massive but decaying Duga Radar, part of a top-secret Soviet military base reportedly built to detect any nuclear attack launched against the USSR in the first few minutes after such ballistic missiles flew.

The over-the-horizon Duga Radar stands 492 feet high and stretches almost 2,300 feet in length. It was built in 1972 to be a signal receiver. The transmitting center was built a short distance away in a town called Lubech-1, now also abandoned.

Yaroslav Yemelianenko, director of Chernobyl Tour, told CNN Travel in a recent interview that “Tourists are overwhelmed by the enormous size of the installation and its aesthetic high-tech beauty. No one expects that it is that big. They feel very sorry that it’s semi-ruined and is under threat of total destruction.”

For years Duga Radar was protected by extensive security measures. Those who were not cleared to know of its existence were told it was part of a summer camp if they caught a glimpse and asked questions. This was not believed by nearly anyone.

More than just a shock to the eyes, Duga Radar was a torment to the ears of many, many people in the broadcasting and radio world. During the 1970s and 1980s, it emitted a sharp and repetitive “rat tat tat tat” noise, interfering with airwaves all over the world. The tapping sound gave the Duga its nickname “The Russian Woodpecker.”

The reason was its power. It consisted of more than 300 individual transmitter elements, operating as high as 10 million watts. Heard on the frequency 10Hz, it became such a problem that in the 1970s amateur radio operators as well as commercial broadcasters began installing Woodpecker Blankers in circuit designs to dull the interference.

Because the Soviets denied its existence for so many years, and after it became defunct still refused to provide more than scraps of information, several theories have taken shape proposing that the Woodpecker’s purpose was more sinister. It did not exist to monitor missiles but to interfere with submarine communications, alter the weather, or exert mind control, they claim.

A hotly debated theory is that the Woodpecker and the Chernobyl tragic accident are related. “All roads lead to Moscow,” says the narrator and protagonist, artist Fedor Alexandrovich, in The Russian Woodpecker, a 2015 documentary (and Sundance Festival award winner) which claims that Chernobyl was premeditated and planned.

Soon after the reactor explosion at Chernobyl, Soviet authorities blamed human error, and the man overseeing the nuclear plant was sentenced to 10 years of hard labor. Subsequently, design flaws were said to have primarily caused the meltdown.

The Soviet Union reportedly spent 18 billion rubles (about $273k) on containing and decontaminating Chernobyl, which drastically worsened its financial crisis. Some analysts say it was the nuclear plant catastrophe that led to the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

The Duga Radar fell out of favor before the final collapse in 1991. Its technology had reportedly become obsolete with the rise of satellite-based warning systems. By 1989, the “Woodpecker” was silenced.

Read another story from us: The Radioactive Dogs of Chernobyl are Being Brought Back into Society

In 2011, the Ukrainian government opened The Zone at Chernobyl to tourists over 18. And by 2017, tourism numbers had risen to 50,000 people a year.