A personal photo in the 21st century typically involves two essential elements — a smartphone (with or without selfie stick), plus perhaps that strangest of facial expressions the “duck face”.

The explanation behind the face is fairly obvious, it’s a modern ritual, but what of the older photographic traditions, such as saying “cheese” before taking the shot…?

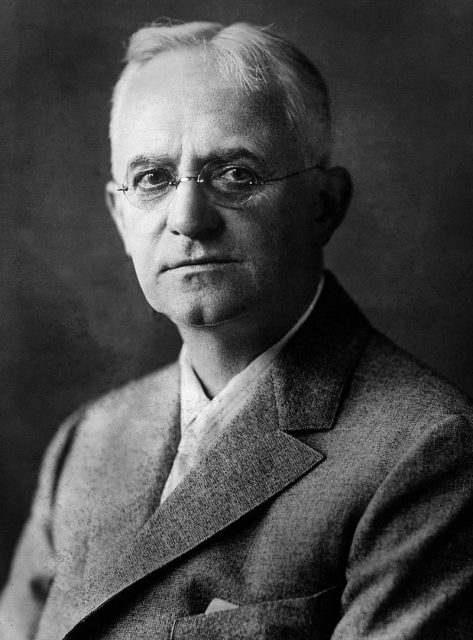

Mention of that particular foodstuff was tied in with Eastman Kodak’s marketing of the camera in the early years of the 20th century. They depicted it as “a tool to record joy,” according to a 2015 Washington Post article.

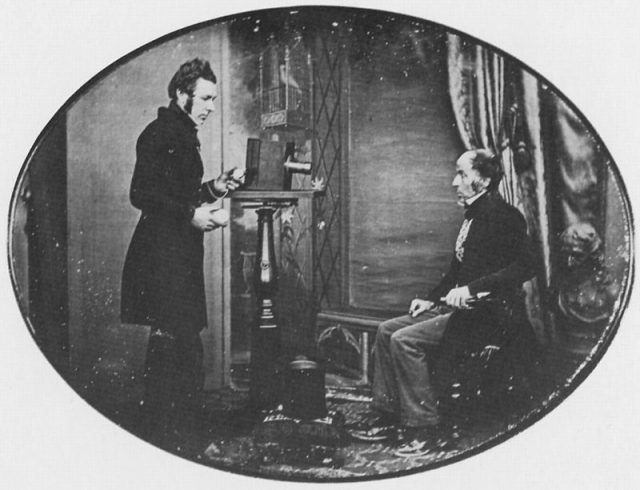

But other food groups were available. 19th century British photographer Richard Beard encouraged his subjects to say “prunes” instead. Why did he do this? Because he wanted a more serious look to those whose lives he captured.

Photography had exciting possibilities, but to begin with in 1839 it was a stiff and mechanical affair aimed at the middle classes. Before Kodak came along the idea was to reflect certain values, and above all not look like a commoner.

The Washington Post quotes historian Christina Kotchemidova, who believes “people were motivated mainly by cultural forces, not practical considerations.”

Writing in 2005, Kotchemidova said “Etiquette codes of the past demanded that the mouth be carefully controlled; beauty standards likewise called for a small mouth.”

A smile or grin had surprisingly unsavory associations. Referring to the work of fellow historian Fred Schroeder, she stated, “In the fine arts a grin was only characteristic of peasants, drunkards, children, and halfwits, suggesting low class or some other deficiency.”

Beard’s use of “prunes” ensured the mouth had a more noble appearance. The fact it made his customer resemble a dead fish was neither here nor there apparently.

Aside from snobbery, there were practical reasons that made a portrait a sluggish experience rather than an upbeat one. It took time to get the image onto the plate. The business used to take hours, and was then refined to a muscle-straining 15 mins.

Related Video: Famous Last Romantic Words

https://youtu.be/GHoSqYj3awk

No-one wanting to smile could be expected to contort their faces for that long. Plus chances were they wouldn’t be keen for people to see inside their mouths anyway.

The Ohio Historical Society wrote about the situation with dentistry in the 1800s, saying that “good dental care was not widely available… dental practices like root canals and caps that allow us to keep our teeth today were not done. The cure for a decayed or broken tooth was often simply to pull it.”

Widely-available treatment eventually arrived and folk felt more comfortable with their freshly-installed pearly whites. Photography however had to play catch up with this new-found optimism.

By promoting cameras and their photos as a means of expressing happiness, Eastman Kodak effectively kicked the pressure-laden portrait into the long grass. The focus was on family fun rather than pomposity. Cheese took the place of prunes.

There was a knock on effect from Kodak’s campaigning. By taking photography out of the studio and into the hands of ordinary Americans, it changed the way people viewed the business of picture taking.

“By the 1920s, companies were using pictures of smiling models to sell everything from canned vegetables to cars,” writes the Post. “Employing the same visual language to sell cameras, Kodak and others had — in a very meta way — installed the smile as one of the ‘standards for a good snapshot.’”

The “prune”-proclaiming Richard Beard was out of the loop by that stage. The website of the National Portrait Gallery mentions that “There were huge profits from his studios in London and Liverpool and from the sale of licences to take daguerreotypes, but Beard was ruined by his many legal actions against rivals.”

Read another story from us: A Historic Look at the World Through the First Photographs Ever Taken

Unfortunately he declared bankruptcy in 1850, at which point his face probably looked a lot like a trout’s. Ironically the very expression that’s now a gold standard in popular culture.