Winston Churchill is one of Britain’s greatest heroes whose life has been the subject of countless books, essays and films. Yet one episode of his early life stands out for its exotic and dramatic setting and the sheer boldness, bravery and luck it took to pull it off. His escape from a South African prison and the accompanying polite letter announcing it to the authorities.

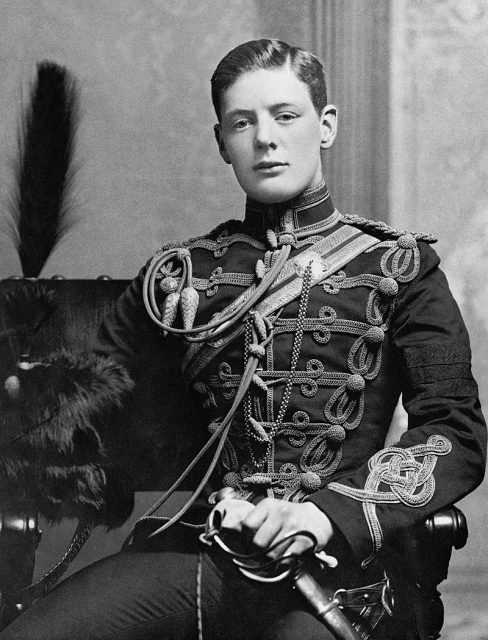

Churchill had come from a prominent aristocratic family. His father held every major office except Prime Minister. His mother was an American socialite and power-player. He was a soldier, journalist, orator, politician, and writer who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953, and his career took off when he escaped captivity as a prisoner of war.

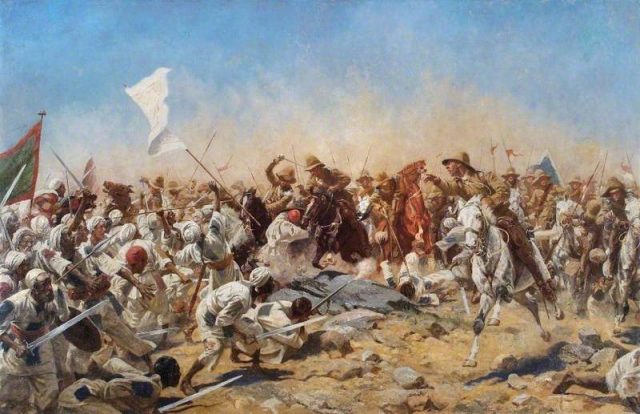

Churchill had served as a soldier in India and North Africa. In the Sudan, he took part in the last great cavalry charge in history. He then “retired” from the military and got a job as an itinerant journalist covering military affairs. His powerful connections and admirers of his mother made sure he was able to get to where he wanted to go when he wanted to go there.

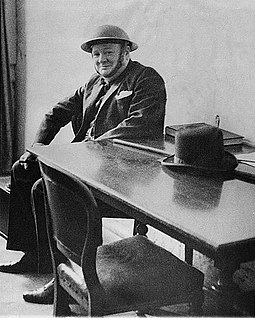

In 1895, he covered the insurrection in Cuba, and his stories, full of bravado and excitement, attracted a following. He ran for Parliament in 1899 but lost the election. That same year, he went to South Africa, where the British and the Dutch Boers were fighting another war for control of the resource-rich territory (the first had occurred in the early 1880s). It was the place to be for an ambitious young man in search of adventure.

Related Video: Greatest Sir Winston Churchill Quotes

https://youtu.be/XRDqImtzxqk

Churchill secured himself a position writing for The Morning Post and arrived in South Africa in October 1899, equipped with gourmet food, eighteen bottles of whiskey, his own personal pistol and khaki uniform and a lot of ambition to see action once again. A month later, he was in the thick of it.

Churchill and a unit of British soldiers were traveling through the South African countryside on a train when they came under fire by Boer “commandos”. The Boers had derailed much of the train and it was in two parts. As the British tried to evacuate to the engine and retreat, they came under tremendous fire, virtually from all sides. Many were wounded.

Though he was just a newspaperman with no official standing, Churchill took over the effort to secure the wounded and get the train moving. Years later, the men who were with him recounted how he seemed to completely dismiss the idea that he could be wounded or killed, and moved about almost sure no bullet would hit him. Years earlier after a battle in India, he had written his mother: “I do not believe the Gods would create so potent a being as myself for so prosaic an ending.”

Massive ego aside, Churchill was brave, of that there is no doubt, and he showed that bravery after he and many of the men with him were captured by the Boers, while some successfully escaped into the bush. Ironically enough, the Boers’ unit commander was Jan Smuts, who would later become the leader of South Africa, a great friend of Churchill and a rock-solid ally.

Word of Churchill’s bravery under fire got back to British lines with the men who had eluded the Boer unit, and Churchill was celebrated as a hero, something he had always wanted, but this was small comfort as the British were taken to a school converted to a POW camp in the Boer capital of Pretoria.

He sat with the other men, some of whom angered Churchill with their attitude – they wanted to wait out the war in safety. Though by the standards of what was to come the POW camp was “cushy” (prisoners were given cigarettes, newspapers, and beer). Notwithstanding all that Churchill hated being penned in. Always possessing boundless energy, he began planning an escape with other POW’s almost as soon as he arrived. He also didn’t want to miss out on the rest of the action, and the chance for further glory.

Churchill and two others planned an escape, but due to Churchill’s impulsiveness, luck and the others hesitation, only he made it over the wall during the night of December 12, 1899. Between him and British-held territory was 300 miles of rough African terrain. In his pockets, he had part of a biscuit and four pieces of melting chocolate. No compass, no water, no map, but loads of self-confidence.

His absence was noticed the next morning, and immediately, notices went up all over Boer territory offering a reward “Dead or Alive” for the “…prisoner of war CHURCHILL”. British spies and telegraph intercepts picked up the news, and within hours, people back home in Britain knew that Churchill was on the loose.

Always a proper gentleman, Churchill left his captors a note. He didn’t address it to the camp commander, but the Boer Minister of War: “I have the honour to inform you that as I do not consider that your Government have any right to detain me as a military prisoner, I have decided to escape from your custody. Regretting that I am unable to bid you a more ceremonious or a personal farewell, I have the honour to be, Sir, your most obedient servant, Winston Churchill.”

At one point, he was hidden in a coal mine by a British settler. He had no lights, but plenty of company: rats. When the settler helped him board a freight train, he hid behind bales of cotton. Only luck prevented him from being spotted when the train was searched. After days on the run, Churchill crossed the border into Portuguese East Africa, today’s Mozambique.

Read another story from us: Exploring the Good and Bad of Winston Churchill’s Legacy

He could have left South Africa and returned home a hero then and there, but he elected to remain. He reported on and took part in the fighting at the Battle of Spion Kop, and led a cavalry detachment through the streets of Pretoria after the British victory, to liberate his comrades in the POW camp.