The last surviving woolly mammoth died out some 3,600 years ago after the species began its certain decline at the end of the last Ice Age, more than 11,000 years ago. However, scientists today are well in the game to restore this huge prehistoric mammal back among the living.

A team of Japanese scientists, led by biologist Kazuo Yamagata from the Kindai University in Japan, has managed to extract the nuclei from mammoth cells and transplant them into a mouse. Within the experiment, the cells did show signs of “life” although their activation was limited.

The cells belonged to a 28,000-year-old mammoth carcass known as Yuka, who at the time of her death would have been seven-years-old. The results of this groundbreaking scientific undertaking were presented in the journal Scientific Reports on March 11, 2019. Yuka, which was retrieved from the permafrost of Siberia in 2010, is one of the most pristine mammoth specimens to have been discovered.

Organic matter such as animal carcasses are indeed best preserved in the permafrost environment — cocooned in severely cold temperatures helps soft tissue, such as skin, fur or brain, to survive.

Regardless of the fact that an astonishing amount of time has passed, Yuka turned out well. Scientists managed to take out 88 nucleus-like structures from the creature’s muscle tissue.

They then inserted the nucleic material into mouse oocytes — the immature eggs (female sex cells) which are produced in the ovaries. In order to ensure reliability of the experiment, the team also implanted cells from an elephant to a control sample.

Upon incubation, some of the mammoth cells were active, although only for a brief period of time. They completed certain processes that take place before actual cell division, including the accurate arrangement of chromosomes to spindle structures before a cell gets to split into two.

Mammoth cell division, however, did not occur. “In the reconstructed oocytes, the mammoth nuclei showed the spindle assembly, histone incorporation and partial nuclear formation; however, the full activation of nuclei for cleavage was not confirmed,” explained the paper abstract.

The scientific effort attests that biological activity can be initiated among cells of creatures that have been dead for a very long time, but that does not mean that the woolly mammoth will be roaming around the planet some time soon.

De-extinction researcher and one of the study’s authors, Kei Miyamoto, told Japanese media that “we still have a long way to go.” Most excited are of course the scientists who have dedicated entire careers to the prospect of bringing extinct species back to life. That the cells implanted with genetic material from Yuka showed at least partial signs of life is seen as a major breakthrough, proving that reactivation of dead cells is not impossible.

Though the full process of cell division was not accomplished, this partial success was an improvement a progress from 2009 when another team used similar methods and carcass that was only 15,000 years old.

Working on even better-preserved sample than Yuka could, in theory, support the next stage of cell division and additional cellular functions such as replication and transcription of DNA. More advanced technology than is currently at our disposal may also be needed for any such undertaking.

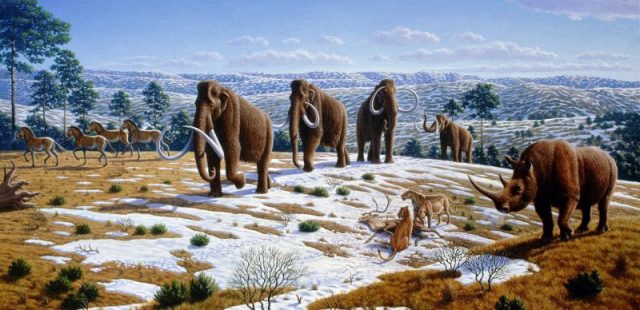

The reasons why woolly mammoths vanished from Earth in the first place have not been fully agreed upon either, but many attribute climate change that came with the ending of the last Ice Age. The rising temperatures likely threatened the majority of mammoth habitats and they began to die out. Some of the last woolly mammoth populations survived in remote regions in Siberia until approximately 9,650 years ago.

The very last of the kin surprisingly made it until circa 1650 BC in an isolated environment on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean. After them, this giant prehistoric mammal completely disappeared.

Early humans may have also contributed to the woolly mammoth demise, hunting them for food and other resources such as their tusks and warm fur.

Read another story from us: New Evidence Proves that Humans did Indeed Hunt Mammoths

Debates remain heated as to whether science should really follow the somewhat controversial quest of accomplishing de-extinction. There are many who believe that reintroducing extinct species more harm than good and that focus should instead go to preservation of species whose natural habitat is already endangered by a vast array of human activities.