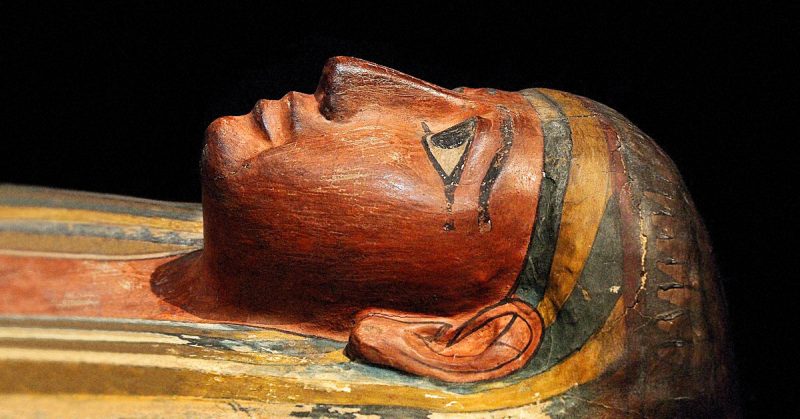

Believe it or not, there used to be a color pigment known as Mummy Brown. To your surprise — or revulsion — the pigment production relied on using real mummies, both human and feline, dug out from ancient Egyptian sites. Other names used for the color included Caput motum and Egyptian brown.

For a few centuries, this usage of mummies persisted; Mummy Brown was a well-loved pigment among a number of pre-Raphaelite painters. Tubes containing the color were being sold as recently as the 1960s.

To produce the paint, ground-up remains of mummies were mixed with white pitch and myrrh, according to the Journal of Art in Society. The result was an alluring, transparent brown hue, something between raw and burnt umber tone.

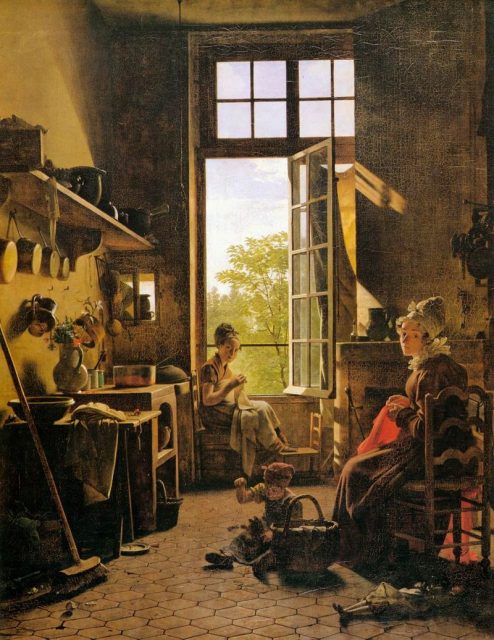

Although it was prone to fading, a number of painters including Eugène Delacroix, Martin Drolling, and Edward Burnes were keen on painting with it. Little did they know they were “resurrecting” the dead in their art studios along the way.

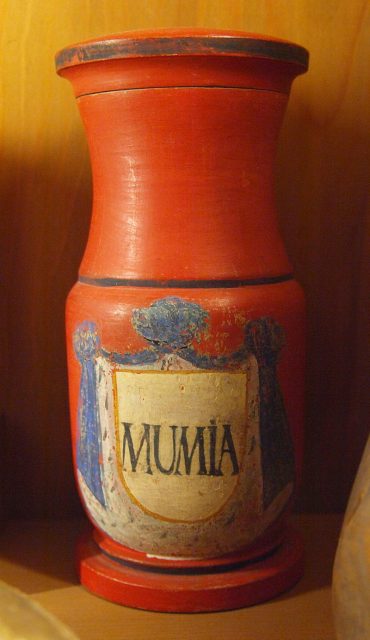

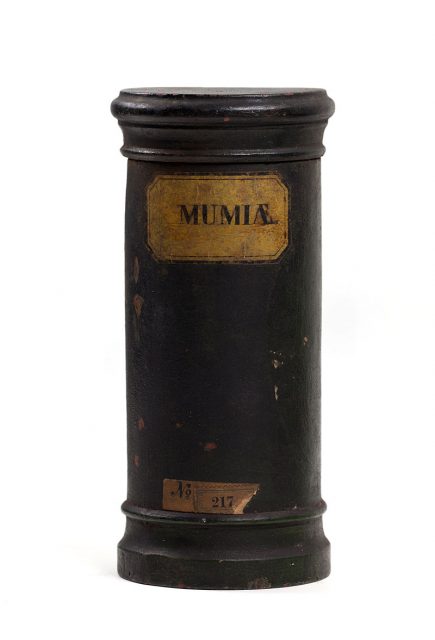

The practice of making color pigment from mummies probably originated from another equally bizarre practice. In Europe, ground mummy was also a prized additive in medicine. People would swallow or topically apply a variety of mummy-based remedies to aid an array of aliments.

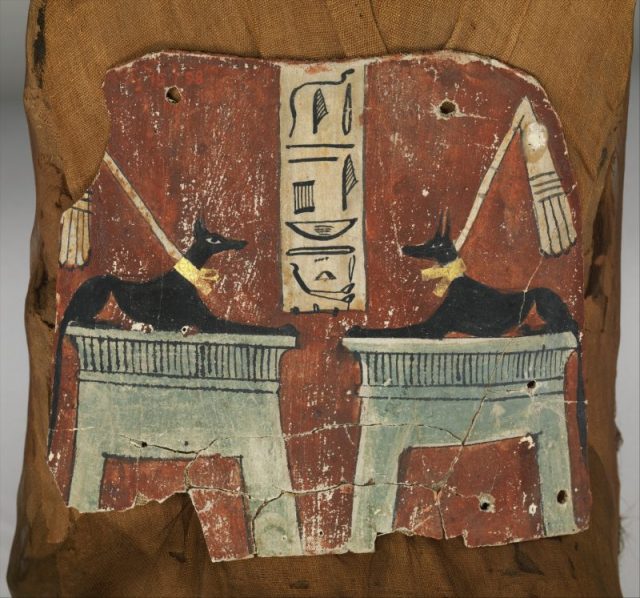

When ancient Egyptians prepared their dearly departed for the afterlife, they used various products to embalm and preserve the body — these included beeswax, resins, spices and sawdust.

Bitumen, a thick, black and oily substance which supposedly provided the brownish tan of the mummy, was another key ingredient in the preservation process. Its Arabic name was mummiya. One reason why mummies were valued in medicine could have been the wrongful assumption people had about bitumen: that it had healing properties.

More than that, people also believed there was an inexplicable, otherworldly life force in mummies. Consumption of mummies, the reasoning followed, would restore the human body to full health. Such claims were backed by famous names of the day, such as Paracelsus, a German-Swiss physician and alchemist who redefined 16th century medicine — and doubtless made a healthy profit from supplying his mummy-based cures.

https://youtu.be/989Lc4Ezoow

And indeed, during the 16th and 17th centuries healing powders from ground mummies became a fairly available “drug” around Europe, prescribed for many things including headaches and sores.

After some time, the demand for mummies in medicine thankfully went out of fashion, but Napoleon’s campaign to Egypt from 1798 to 1801 announced the beginning of yet another craze about anything Egypt. Now it was time for art to benefit from mummies…among other things.

Mummies became so increasingly popular again that “tourists brought entire mummies home to display in their living rooms, and mummy unwrapping parties became popular,” according to the National Geographic.

Although attempts were made to ban imports of mummies, many were still shipped across the Mediterranean. They were “brought over from Egypt to serve as fuel for steam engines and fertilizer for crops, and as art supplies.”

Not all artists who used Mummy Brown knew they were using a color made up of people who had lived and died thousands of years before them. Some of those artists got pretty upset when they were updated about the pigment’s contents and were quick to put a halt on any usage of the color.

Edward Burnes opted to bury the tube of Mummy Brown. A statement given by his wife, Georgina, recollecting how he found out the vicious truth about the pigment is widely cited:

“Edward scouted [scornfully rejected] the idea of the pigment having anything to do with a mummy — said the name must be only borrowed to describe a particular shade of brown — but when assured that it was actually compounded of real mummy he left us at once, hastened to the studio, and returning with the only tube he had, insisted on our giving it decent burial there and then.”

Read another story from us: Female Mummy Hunters and the Remarkable Impact They Made

As word spread, more and more people began to realize what wrongdoing was being done here and how this undermined the study of ancient Egyptian civilization. Real Mummy Brown disappeared from color palettes. Tubes tagged as mummy brown can be found today, but — we hope — they do not contain any mummified remains.