During the Revolutionary War (1775-1783), some 231,000 men fought for America in the Continental Army. In essence, the war was fought because colonists, living in British North America, rebelled against the crown.

They became known by many names, including Revolutionaries, Patriots, Yankees, Whigs, and Continentals, while those who fought for the Crown were called Loyalists, Royalists, Tories, and the King’s Men. Many men took up the call to arms to fight against Britain to secure American independence.

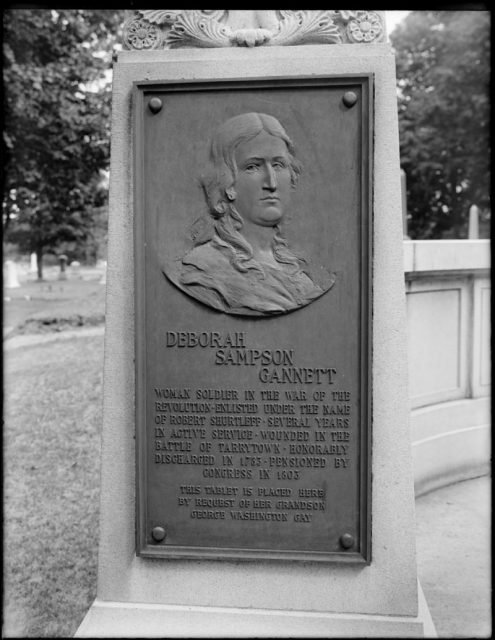

However, just like today, women were restricted from combat roles (in the U.S. today, women are still banned from direct combat positions in the infantry and as machine gunners). One particular woman, Deborah Sampson, disagreed and decided to do something about it.

Born in Plympton, Massachusets in 1760, Deborah was one of seven children in her modest household. Told that her father disappeared at sea, in reality he likely abandoned his family, leaving her mother alone with several children.

As a result, she was forced to put them into the care of other family members and friends, which was not uncommon in the 18th century. Deborah was first placed with one of her mother’s relatives, and later, after her mother died, sent to live with a widow in her 80s. It was probably here that she learned to read.

When the widow died in 1771, Deborah was sent to live with the family of Jeremiah Thomas, where she worked as an indentured servant until 1778. Thomas, who did not believe that women should or needed to be educated, did not send his girls or Deborah to school.

So Deborah learned instead by sharing schoolwork from Thomas’ sons. As a result of her self-education, Deborah was able to make a living as a teacher once she left her service with the Thompson family. She was also a highly skilled weaver and adept at carpentry, making milk stools and sleds, as well as tools for her weaving.

It wasn’t until 1782, however, that she decided to put aside her teaching career and enter the army. She cut her hair, put on men’s clothes and joined the army unit in Middleborough, Massachusetts, using the name Timothy Thayer.

Much taller than the average woman at 5’ 9”, Deborah was also broad and strong, lending to her ruse. She collected her enlistment bonus but failed to meet up with her company as a local resident had recognized her when she signed her enlistment papers. She paid back the bonus and was not punished by the army.

Undeterred, Deborah tried again that same year, this time under the name Robert Shirtliff (also spelled Shurtleff), joining the 4th Massachusetts Regiment’s Light Infantry Company.

https://youtu.be/qWC1zUDlaWQ

Light Infantry companies often chose men who were stronger and taller than the average soldier; the elite nature of this unit may have actually helped Deborah, as it was highly unlikely that anyone would look for a woman among a group of men chosen specifically for their physical abilities.

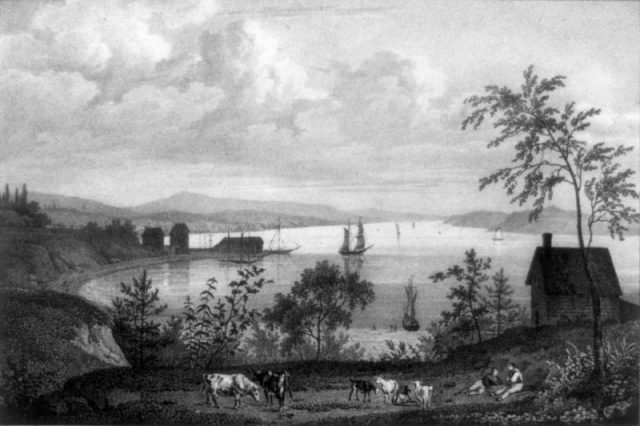

Her disguise worked, and Deborah fought as “Robert” in several skirmishes. In her first battle outside Tarrytown, New York, on July 3, 1782, she was wounded in the thigh by two musket balls and received a cut on her forehead. Begging her fellow soldiers to let her die so she would not to have to see a doctor, she was taken to a hospital nonetheless.

After her head had been treated, she quickly left the hospital and tended to her leg herself, removing only one the musket balls with a penknife and sewing needle. The other ball was too deep, and her leg never fully healed.

On April 1, 1793, she was reassigned as a waiter to General John Paterson. That summer, she fell ill in Philadelphia and was treated by a doctor, Barnabas Binney, who discovered her true identity. He did not report her, however; instead, he took her to his house where his family and a nurse looked after her.

Binney discretely revealed her gender to General Paterson, but, instead of being reprimanded and released like other women who had tried to serve in the Army, Paterson gave Deborah an honorable discharge, some words of advice, and enough money to make the trip home. She was officially discharged from West Point, New York, on October 25, 1873.

After her war service, Deborah married a farmer from Sharon, Massachusetts, named Benjamin Gannett. Together, they had three children and adopted a fourth. The family struggled, however, to keep their small farm afloat. So in 1792, Deborah petitioned the army for pay that had been withheld from her since her discharge and was awarded 34 pounds (the currency of the time), plus interest.

Deborah also began to give lectures about her wartime service. She supported traditional female roles but also donned a uniform during her lectures and performed military drill. She was paid for these lectures but still did not make enough to support her family, eventually resorting to borrowing money from a friend, Paul Revere.

Revere wrote to a U.S. Representative, William Eustis, requesting that Deborah receive a military pension – something that had never been granted to a woman: “I have been induced to enquire her situation, and character, since she quit the male habit, and soldiers uniform; for the more decent apparel of her own gender…humanity and justice obliges me to say, that every person with whom I have conversed about her, and it is not a few, speak of her as a woman with handsome talents, good morals, a dutiful wife, and an affectionate parent.”

Congress approved the request in 1805, and Deborah received $4 per month as a result. Her pension was later adjusted in 1816 to $76.80 per year, and she was able to repay all her loans and make necessary improvements on her family farm.

In 1827, Deborah Sampson came down with yellow fever and died. She was 66 years old. She is buried in Sharon, at Rock Ridge Cemetery. A statue of her stands outside the public library, and her family home is protected as a historic homestead. A ship was named in her honour during the Second World War.