When humans and all they bring move into a new area of the planet, it’s hard to know what the impact will be on the local habitats. Even when we’re trying not to, human habitation can have a major impact on the land around them, influencing the local flora and fauna in unexpected ways. One excellent example of this phenomenon is that of the extinction of the Lyall’s wren.

According to New Zealand Birds Online, the entire species was both discovered and made extinct by a cat belonging to a lighthouse keeper.

The lighthouse was built in 1892, on Stephens Island in New Zealand. The Lyall’s wren may or may not have been spotted by the men who were building the lighthouse, but the creatures absolutely came to human notice two years later, when assistant lighthouse keeper David Lyall moved in with a few others to take over its operation.

Lyall was a naturalist and was looking forward to being able to pursue his interests on the largely uninhabited island. Because there were so few people stationed at the new post, Lyall brought his pregnant cat, Tibbles, with him for companionship.

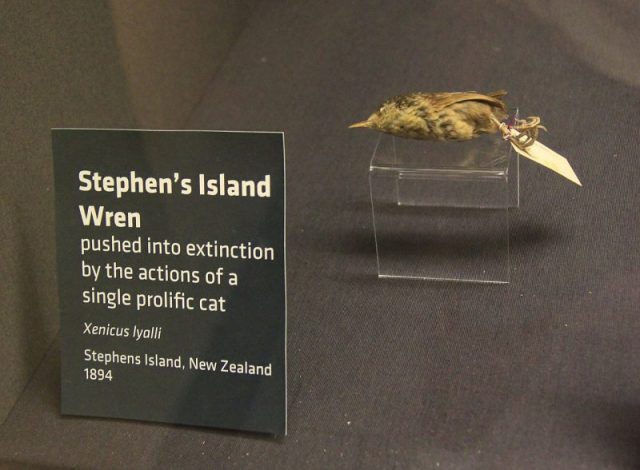

Lyall’s wren was described as a small, drab bird with large feet and a solid bill and legs. Its back was olive green, edged in dark brown. Its flight and tail feathers were the same brown, and it had a yellow stripe near its eye and a paler chest.

The other thing that set this small wren apart from most other birds was the fact that it couldn’t fly. Its chest lacked a keel to anchor the muscles necessary for flight, and its wings were small and rounded, with soft, loose feathers that weren’t airtight enough to provide any lift. In other words, the wren was a sitting duck.

As Station Gossip recounts, it didn’t take long for the damage to be done. Cats are highly efficient predators who have a strong instinct for the chase and will kill even if they’re not hungry. Sometimes they bring their spoils to their owners as gifts or trophies. Tibbles did, which is how the Stephen Island wren came to David Lyall’s attention.

As the cat brought her owner various catches, Lyall found he could identify all of the species he was receiving, except for one. He was excited when he discovered that not only could he not identify the little wren, but neither could any other people he knew. He carefully prepared specimens from the examples Tibbles had provided and sent them out to some of the most well-respected ornithologists of the time.

One of those experts quickly determined that the birds, were, in fact, a previously unknown but distinct species. The experts began to write about the bird in specialty journals, and one of them bought several specimens from Lyall at an enormous price.

A third of the experts suggested that the species be named Traversia lyalli in honor of Lyall, the man who first saw the birds and made them known, and H.H. Travers, the naturalist who helped Lyall find specimens.

While all of this was going on, time passed. Tibbles had her kittens, who in turn got old enough to reproduce — and the population of feral cats on Stephens Island began to grow. Besides hunting for fun, cats need to eat, and the feline population found a ready food source in the small birds who couldn’t fly to safety.

Although there’s a reason to believe that the species was once found all over New Zealand, their vulnerability due to their lack of flight meant that their populations were demolished in most of New Zealand. Only the lack of predators on Stephens Island had prevented the same thing from happening there. Tibbles and her offspring put an end to that.

Less than a year after the Lyall wren’s initial discovery, it was pretty well extinct. In February of 1895, the lighthouse keeper wrote a letter to Walter Buller saying that the cats had been decimating the population of the small birds. By the time the letter was written there had only been two sightings of live birds; all the others were brought to him by his cat.

A month after that, an editorial in a Christchurch paper noted that the bird seemed to be completely extinct and said that it was possibly the fastest known case of obliterating a species.

It’s possible that there may still have been a few specimens living for another year or two after that, as some sources say that another one or two examples of the wren trickled in, but Tibbles and her descendants still eradicated the species in record time, becoming the poster animals for the dangers of keeping outdoor cats.

By 1898, a new lighthouse keeper was installed on the island, who shot and killed over 100 feral cats in his first nine months on the island, although it wasn’t until 1925 that the island was completely cat-free.