Before the Secret Garden was even a thought in Frances Hodgson Burnett’s mind, another lost treasure was being developed in the southwest of England.

Known for some of the best weather in the country, Cornwall has several claims to fame. Birthplace of author William Golding, scene for The Pirates of Penzance, home to the St Austell brewery, it also contains some lesser known, but just as worthy wonders.

The Heligan estate is a palatial manor house with surrounding parklands first built in the 1200s. It wasn’t until the 16th century that the wealthy Tremayne family moved in, and another two centuries before they started cultivating what is now known as the Lost Gardens of Heligan.

Where did this verdant gem get its name? The word Heligan comes from the formerly extinct Cornish language and means “willow tree.” The estate earned this name for obvious reasons.

The gardens are considered lost because there was a 75 year period during which they were soundly forgotten. The manor house, as well as the surrounding grounds, play a large role in local history that explains why the gardens were lost and what makes them so special.

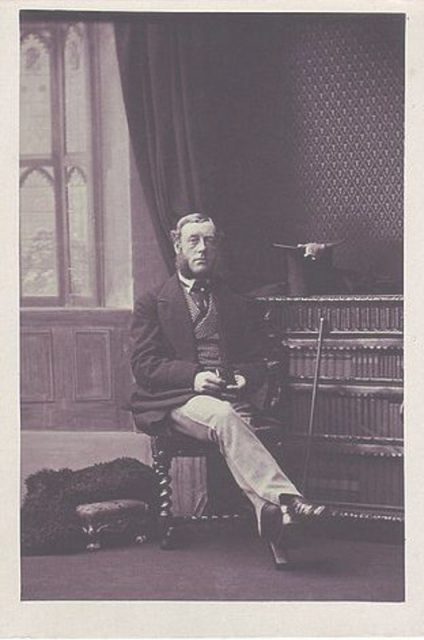

Surrounded by over 200 acres of parkland, Heligan House was well staffed. Over the years, the Tremaynes passed a proclivity for their pretty park from father to son, paying special attention to the horticultural development of the gardens of Heligan.

The family regularly employed an impressive number of green thumbs, mounting up to a total 20 full-time gardeners at the estate’s height.

Starting in the late 18th century, the Tremayne family began to work on more than just a classic English-style garden. The grounds contained impressive specimens of some of the oldest propagated rhododendrons and camellias which win awards even today, a jungle garden filled with exotic plants collected from across the world, and Europe’s first pineapple pit: a considerable scientific development of the time, allowing the growth of the tropical fruit in colder temperatures.

When and why did such an impressive venture collapse? Naturally, the outbreak of World War I had far-reaching effects across the country. Though the Tremayne family had money, they couldn’t keep their staff from going to war.

The men working in the Heligan gardens were conscripted and the garden — acres upon acres of luscious greenery — saw a swift end in a time it had just reached its pinnacle.

From the onset of war, the gardens were doomed as the manor house took priority. It was turned into a convalescence hospital and later, in World War II, it was used by American troops as a base. The house was completely repurposed by 1970, when it was broken down into flats and rented out.

By this point, the gardens of Heligan were officially lost.

Another reason the estate lost its stately grandeur was due to the death of the presiding Tremayne. Known as Jack, the last heir to the estate died unmarried and childless. Heligan was conferred to a trust made up of extended family. By this point, no one remembered the existence of the gardens.

After the Burns’ Day Storm — a devastating and record-breaking hurricane that struck the British Isles in 1990 — a metaphorical key was found to the Heligan gardens. In clearing debris, the walls to the derelict garden were rediscovered as well as a historic inscription, dated August 1914: “Don’t come here to sleep or slumber.”

Those who cleared the wreckage and set out to redevelop the Heligan gardens certainly maintained the motto. The project was supported by Tim Smit, who is best credited with the Eden Project: the largest greenhouse in the world. The Lost Gardens of Heligan may be of humbler origins, but their majesty is undeniable.

Read another story from us: The stunning Highcliffe castle

In the past 30 years, the gardens have been cultivated and restored to mirror the grandeur they knew in the time of the Tremayne family. The Lost Gardens welcome visitors year round and offer guests the chance to spend a day surrounded by a beautiful view.