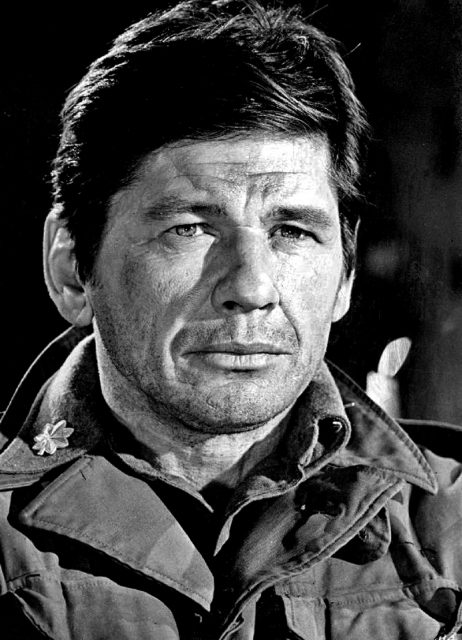

Charles Bronson became famous as a big screen hard man. When it came to real life however, his early days were tougher than any one man vigilante hunt. Growing up in a mining community, Bronson eventually emerged from the darkness as one of the world’s best-paid movie stars. There was back-breaking labor and much personal frustration along the way.

Finding out about his background wasn’t an easy process. The actor had a reputation as an unforthcoming interviewee. “All conversation with Bronson has a tendency to stop,” the late Roger Ebert wrote in 1974, quoted from his website. “His natural state of conversation is silence.”

Yet sometimes he would give people an idea of what it was like growing up in the borough of Ehrenfeld, Pennsylvania. He was born there in 1921 as Charles Buchinsky, to Lithuanian couple Walter and Mary. Bronson was their 11th child but they went on to have 15.

The place had another name — “Scoop Town”, which came from the mining operation there. It was run by the Pennsylvania Coal and Coke Company, leading to some difficult situations. Ehrenfeld wasn’t renowned for its health and safety record. The Buchinskys were evicted from their company-owned home at one point as part of a general strike before Bronson had even started school.

“I remember my father had shaved us all bald to avoid lice,” he recalled to Ebert. “Times were poor. I wore hand-me-downs. And because the kids just older than me in the family were girls, sometimes I had to wear my sisters’ hand-me-downs… And my socks, when I got home sometimes I’d have to take them off and give them to my brother to wear into the mines.”

It was Bronson who entered the mines as a teenager. Walter had passed away when his son was just 10, though reportedly the pair weren’t close. It was dangerous and dirty work below ground, with long hours and little reward. When the miners got outside there were still perils to be avoided.

“The water was full of sulphur,” Bronson said. “There was nothing to put a hose to.” But greater hazards lay in wait under his very feet. “There were unpaved streets covered with rock and slag. You had the rock dumps always exploding. They were always on fire, down inside, and if it rained for a long enough time, the water would seep down to the fires and turn to steam and the dump would explode.”

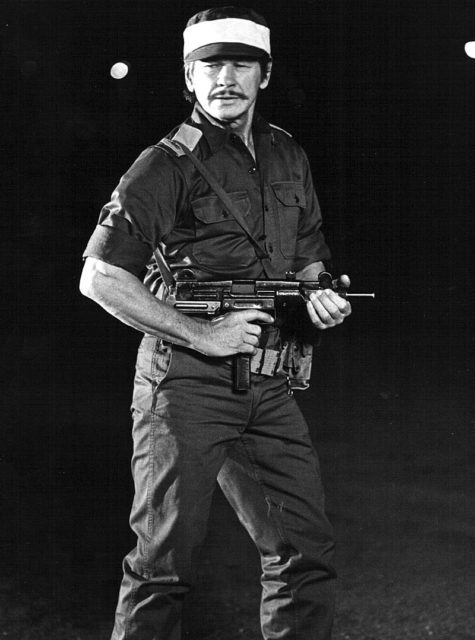

Michael Winner, the English director with whom Bronson collaborated frequently, spoke about the star in a 2011 piece for the Telegraph. Referring to his early life he said, “he was saved only by the war. He became a soldier and after the war American soldiers were paid to learn a trade, and he decided to learn acting.”

Roger Ebert writes how Bronson regarded the draft as “the luckiest thing that ever happened to him.” He’d spent four years half-killing himself and the prospect of getting out and seeing the world was rich indeed. An older brother apparently also thought dodging bullets was preferable to working for the mining companies.

“When I worked, the rate was a dollar a ton,” he revealed. “You spent one whole day preparing so you could spend the next day getting it out… in those days, that was pure work. It wasn’t a man on a dock with a forklift or any of that bull****. It was pure work.”

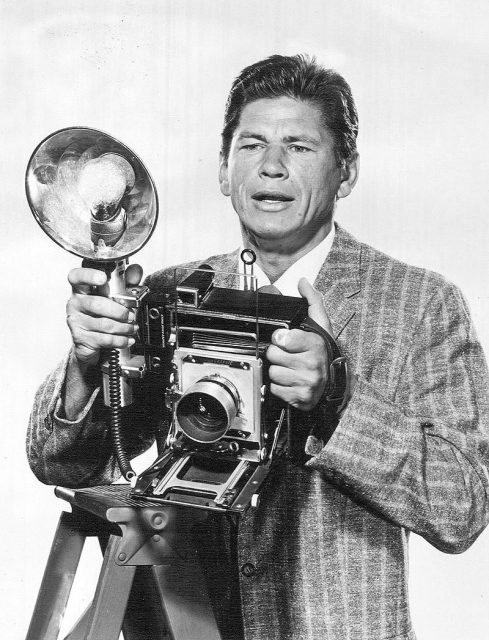

He struggled as a miner and subsequently struggled to establish his name in lights. He was “said to be the world’s most popular movie star. Not America’s.” He first found fame in Europe, via a French thriller. His obituary in the New York Times says, “the release of… ‘Rider on the Rain’ in 1969 convinced many naysayers that Mr. Bronson had a great deal of artistic skill that Hollywood’s casting directors had squandered.”

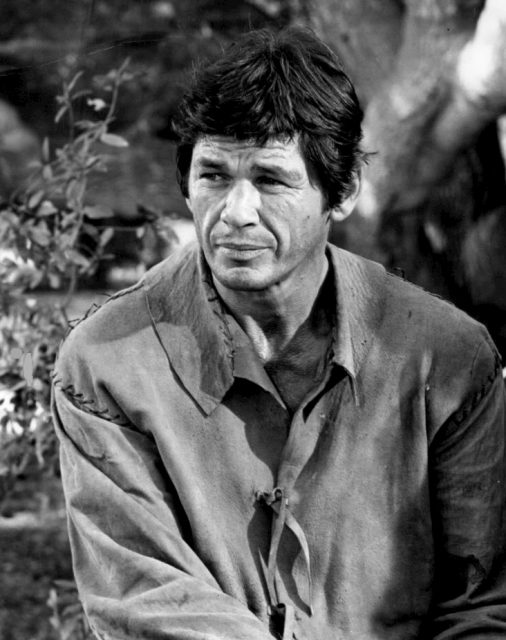

The likes of Michael Winner’s Death Wish (1974) and other gritty efforts got him onto the A List when he was in his 50s. Before that he’d appeared in war movies and Westerns such as The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Dirty Dozen (1967), Once Upon A Time In The West (1968) and Chato’s Land (1972).

Toward the end of his career he was associated with the Death Wish sequels, though Sean Penn cast him in his acclaimed directorial debut The Indian Runner in 1991. Bronson retired in 1998 and died in 2003.

He left the life of a miner behind, but the experience it seems never left him psychologically. Bronson wrote a screenplay about a mining town, titled $1.98, which went unproduced. He also had the temperament of his former existence. Quoted by Roger Ebert, cinematographer Arthur Ornitz said “he sits over in a corner and never talks to anybody. Usually I’ll kid around with a guy, have a few drinks. I think there’s a little timidity there. He’s a coal miner.”

The book Menacing Face Worth Millions by Brian D’Ambrosio (2012) writes that “Relatives and neighbors recall him as shy, sensitive, mischievous, a loner.” And he may have beat up bad guys onscreen, but the man himself liked to contemplate art more than crunch bones.

“He told interviewers that he had been in fistfights and had been arrested on charges of assault and battery,” the Times says, “and he liked to suggest to journalists that his hobby was knife-throwing. But reporters… learned that Mr. Bronson’s hobby was painting and that he was a quiet, personable, gentle man.”

Read another story from us: The Superfan who Left her Entire Fortune to Charles Bronson

It’s worth remembering that his most famous character — architect Paul Kersey from Death Wish — was opposed to violence before the traumatic incidents that transformed him into a hardened crime fighting machine. Bronson certainly knew what things were like at the sharp end. Thankfully he ended his days in relative comfort.