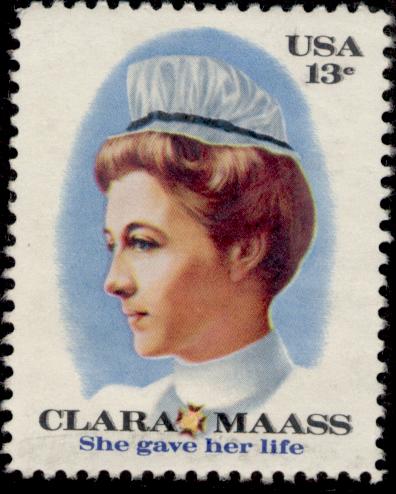

How much would you sacrifice in the name of science? Clara Maass, a brave, battle-tested nurse from New Jersey, agreed to take part in medical experiments to find a cure for yellow fever — and paid for her dedication with her young life.

Maass volunteered as a nurse for the United States Army during the Spanish-American War, serving in Florida and Georgia, as well as in Santiago, Cuba, caring for soldiers stricken with a wide range of diseases, including malaria, typhoid fever, dysentery, and, yes, yellow fever. This was no small task: During the war, more soldiers succumbed to yellow fever alone than were killed in battle.

She was discharged in February 1899, but shortly thereafter, in October of 1900, Maass returned to Cuba to work with the U.S. Army’s Yellow Fever Commission.

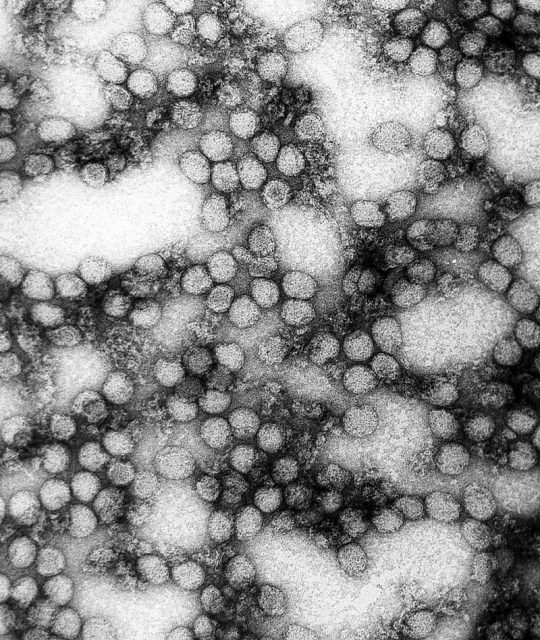

The disease, something of a mystery back then, was running rampant in post-war Cuba. The Commission wanted to learn how it was being spread — by mosquito bites or through contact with contaminated objects.

In the fall of 1900, Dr. William Gorgas sent out word that he was looking for volunteers to help with his experiments. Typically animals were used for medical research but at the time scientists didn’t know if they could contract yellow fever.

Human-beings, it was decided, would be the ideal test subjects. To encourage people to sign on the dotted line — potentially risking their lives — a fee of $100 (approximately $3,000 in today’s money), was promised, with an additional $100 given to those who contracted the disease.

Maass didn’t hesitate — pretty astonishing, considering that the young nurse knew just how deadly yellow fever was, having watched soldiers succumb to the disease during her years as an Army nurse. In March 1901, Maass was bitten by a Culex fasciata mosquito that had been feeding on yellow fever patients. She contracted a mild case of the disease but quickly bounced back.

This proved frustrating for researchers: They were fairly certain that mosquitoes were transmitting the disease but lacked the evidence to prove it because volunteers who were bitten remained healthy. So far.

And so, Maass agreed to continue taking part in the trials. Five months later she was bitten again by an infected mosquito. This prick, however, would prove fatal.

Maass fell ill on August 18th and died less than a week later, on August 24, 1901. Her death, at age 25, led to a public outcry over people being used as human guinea pigs, and the experiments were eventually halted.

Maass was buried in Havana but the U.S. Army later moved returned her body to her native New Jersey, where it remains today, in Newark’s Fairmount Cemetery.

Over the years the courageous young woman has gotten her due. A granite gravestone with a bronze plaque has been erected to replace a plain marker that once adorned her gravesite.

Read another story from us: The Vicious Battle Between the Vatican and Cats

A hospital in Belleville, New Jersey has been named in her honor. Cuba issued a postal stamp in her honor in 1951, on the fiftieth anniversary of her death. And in 1976, the U.S. Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp in Maass’s honor, on the 100th anniversary of her birth.