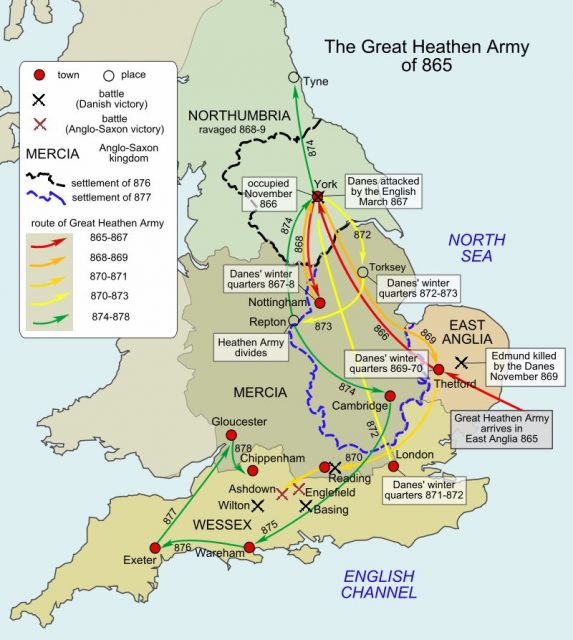

Beginning with the attack on the island monastery of Lindisfarne in 793 AD, Viking raids on England had become almost routine, but in 865 AD this changed for the worse and the English faced what they called “The Great Heathen Army.”

This was an invasion force of thousands of Norse warriors, most of them from Denmark, but others from Norway, Sweden, and Ireland, and under the command of Ivar the Boneless and his brothers, Halfdan and Ubba, who had made their names in Ireland fighting for Olaf the White, ruler of the Viking Kingdom of Dublin, in the 850s. England in the 9th century was divided between four major Anglo-Saxon kingdoms — Northumbria in the north, Mercia in the middle of the country, East Anglia in the east, and Wessex covering much of the south.

By the time of Ivar’s end sometime after 870, Viking territory in England, called “the Danelaw”, covered the bulk of Northumbria, Mercia, and East Anglia. Norse influence stretched from the River Tees to the River Thames, shaping the language, culture, and geography of the north and east of the country. This was down to the leadership of a warrior chief who struggled to walk, but according to legend had to be carried into battle on an upturned shield.

According to Norse mythology, Ivar the Boneless was born with “only cartilage was where bone should have been, but otherwise, he grew tall and handsome and in wisdom, he was the best of their children.” His father was said to be Ragnar Lodbrok, the main character in the first four seasons of Vikings, and as punishment for forcing himself on the mother, the sorceress (or völva) Aslaug, their child was cursed with deformity.

Many believe Ragnar, who is played by Travis Fimmel in the show, to be a fictional character. He’s a sort of every(North)man narrator who is used in order to contextualize important events in Viking history. It’s a way of binding together folk tales and oral histories from different regions, eras, and traditions as the Norse world expanded through exploration and conquest.

Related Video: Beautiful and mysterious Viking treasures

Some modern theories are that Ivar could have suffered from osteogenesis imperfecta (brittle bone disease), that he was double jointed, or that rather than being literally boneless, there’s a line in the 13th century saga Ragnarssona þáttr (Tale of Ragnar’s Sons) that suggests it may be a euphemism for his impotence.

The sagas offer more noble and heroic reasons for the invasion by the Great Heathen Army, suggesting that Ivar the Boneless and his brothers were simply avenging the betrayal and killing of Ragnar by the lowborn King Ælla of Northumbria, but that’s most likely an attempt to retrospectively give the invaders a more noble motive than mere plunder.

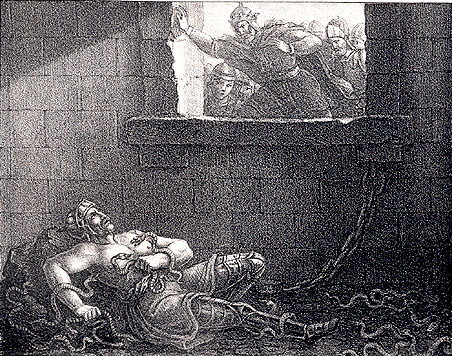

Even if Ragnar were a real historical figure, it doesn’t seem hugely likely that Ælla kept a pit of venomous snakes to have his captives thrown into like a supervillain, especially given there are no species of snake in the British Isles that are lethal to humans.

It’s much more plausible that the “betrayal” and the snake pit are allegories, as Ælla was regarded by his peers as a usurper, who had displaced the true king, Osberht, giving Norse storytellers a convenient bad guy for their own tales.

The Great Heathen Army did, however, turn on Ælla of Northumbria first. Landing in East Anglia to little resistance, they marched north to capture York in 866. This would be the capital of their new English domain. Ælla, and his predecessor Osberht, faced the greater threat together and were killed in battle near York in March 867 and replaced with a puppet king, Ecgberht I, who accepted Viking rule of the territory taken by Ivar the Boneless.

The sagas give different, more poetic interpretations of these events. They claim that Ivar went to broker peace with Ælla and took York from him using his greater cunning. Asking for compensation from the King of Northumbria for the murder of his father, Ivar said he would take whatever land he could cover with a piece of ox hide.

Ælla, thinking his opponent could do little harm with a patch of Northumbria, agreed. Ivar then cut the leather into thin strips that he could stretch around a parcel of land big enough to settle the city of York. (As York had already been an important Roman and then Anglo-Saxon city, this is most likely nonsense.)

Having subdued their northern neighbors, the Great Heathen Army then turned west and south and invaded the Kingdom of Mercia and then, eventually — after buying time with a peace treaty he had no intention of honoring — the Kingdom of East Anglia. King Edmund of East Anglia was defeated in battle and according to Anglo-Saxon sources is done away with for refusing to turn his back on Christianity.

While his kin launched an ultimately unsuccessful invasion of the Kingdom of Wessex, Ivar the Boneless returned to Ireland and joined his old ally Olaf the White in a raid on Dumbarton, the capital of the Celtic (or Brythonic) Kingdom of Strathclyde on the west coast of Scotland. Returning to Dublin in triumph with loot and slaves, Ivar the Boneless died sometime after 870, with one source giving the date as 873.

“The Norwegian king […] died of a sudden hideous disease,” recorded the 11th century Fragmentary Annals of Ireland cheerfully. “Thus it pleased God.”

Read another story from us: Viking Homes Contained a Portal to the Afterlife

Want to become a trivia master? Sign up for our Today In History newsletter!

Some historians believe that it may have been a result of his deteriorating condition, but until an archaeologist stumbles across his distorted bones buried beneath an unassuming Irish hillside, there’s simply too little detail and too much mythology to know for certain. What we do know, is in fewer than ten years Ivar the Boneless left a mark on history that can still be seen in Norse place names, dialect words, folklore, and on our TV screens.